November full moon 2025: The Beaver supermoon will be the biggest and brightest of the year

November's full Beaver Moon will occur on Nov. 5 and will be the biggest and brightest moon of 2025.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The full moon of November, called the Beaver Moon, will be full illuminated on Nov. 5 at 8:19 a.m. Eastern Time (1319 GMT), according to the U.S. Naval Observatory. This moon will also be a "supermoon," meaning the full moon coincides with our satellite's closest point to Earth in its elliptical orbit. It will be the biggest and brightest full moon of 2025.

Two days later, the just-past full moon will occult Beta Tauri, otherwise known as Elnath. The occultation will be visible from South America and Africa and take place on the night of Nov. 7-8.

The moon is called full when it is exactly opposite the sun in the sky (from the perspective of the Earth). The position is measured where the moon is relative to Earth itself rather than any given location, so the time depends on one's longitude. This full moon occurs in the morning hours on the east coast of the Americas, and in the afternoon in Europe; to catch the moon at the moment it reaches full phase, one has to be in Asia or the western coast of North America (in which case one will catch it just before the moon sets and the sun rises).

Article continues belowFor example, in Los Angeles, the full moon is at 5:19 a.m. Nov. 5, and moonset is at 6:31 a.m. Sunrise happens before the moon sets, at 6:17 a.m., so the two will share the sky, albeit briefly. Further west, in Honolulu, the full moon is at 3:19 a.m., well before sunrise at 6:37 a.m. local time.

The full moon happens in the evening hours in cities such as New Delhi, where full phase is at 6:19 p.m. and moonrise is at 5:11 p.m. local time. (sunset is at 5:33 p.m.), and in Tokyo, where the full moon occurs at 10:19 p.m. As one goes further east the full moon occurs after midnight; in Sydney, Australia, the full moon is at 12:19 a.m. Nov. 6.

In New York City, the moon rises at 4:35 p.m. Eastern; sunset is at 4:47 p.m. As in Los Angeles, one will be able to see the setting sun and the moon in the sky simultaneously, though only for a few minutes.

A full moon's maximal altitude in the sky reflects the sun's in six months — so, for example, from New York, where November is in late fall, the moon will reach its highest point in the sky at 12:12 a.m. on Nov. 6, 72 degrees above the southern horizon. This is similar to where the sun would be in early May at local noon. In the Southern Hemisphere, where November is late spring, the moon is only about 32 degrees above the northern horizon at 1:38 a.m. Nov. 6. This is one reason that for Northern Hemisphere observers, wintertime moons often appear brighter; it's because they are generally higher in the sky.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This full moon is a "supermoon" because it happens when the moon is at a point in its orbit where it is closer to Earth. The moon's orbit is nearly circular, but not exactly so. The moon's average distance is 238,854 miles (384,399 kilometers), but since its orbit is an ellipse, it can be as close as 221,460 miles (356,400 km). In this case, the moon will be about 221,700 miles (356,800 km) away, and will appear slightly brighter and larger than a "normal" full moon. However, the difference is relatively small, on the order of 11 percent, so it's unlikely to be noticed by any but the most careful observers.

Moon occults Beta Tauri

On Nov. 8, the just-past-full moon will occult the star Beta Tauri, also known as Elnath. Beta Tauri is visible all night in mid-northern latitudes and is known for being shared between Taurus and Auriga. To see the occultation, one needs to be in South America or western and central Africa.

Formosa, Argentina, is near the western end of the zone where observers can see both the disappearance of Beta Tauri behind the moon and its reappearance. Beta Tauri will appear to touch the right (eastern) side of the rising moon at 11:03 p.m. local time on Nov. 7; the moon will be low in the northeastern sky. The star will reappear at 11:34 p.m. from behind the left side of the moon.

In Bolivia, from Santa Cruz, the occultation will start at 9:43 p.m. local time and end at 10:43 p.m., with the moon, as in Argentina, low in the sky, about 7 degrees above the northeastern horizon. From Santa Cruz, Elnath will look as though it disappears behind the lower right half of the moon and reappears on the upper left.

The occultation will be visible in most of Brazil, though not in either Rio de Janeiro or São Paolo. In Brasilia, the moon will be higher in the sky, about 23 degrees, and Elnath will disappear at 11:01 p.m. local time, and reappear at 11:54 p.m.

In Africa, the occultation is in the predawn sky; in Dakar, Senegal, the occultation starts at 3:06 a.m. local time and the moon will be almost straight up, a full 75 degrees above the northern horizon. Elnath will disappear behind the eastern side of the moon and reappear on the western side at 4:29 a.m.

Visible Planets

Want to see full moons and other awesome stuff in the night sky? The Celestron NexStar 4SE is ideal for beginners and provides crisp, clear views of a wide range of objects. For a more in-depth look at our Celestron NexStar 4SE review.

On the night of the November full moon, Saturn will be the first planet visible for mid-latitude Northern Hemisphere sky watchers. By 6 p.m., the sun has been down for more than an hour and the sky is dark; Saturn will be 32 degrees high in the southeast, a bright yellow-white "star" that will be easy to spot — especially in urban, light-polluted regions — because the stars around it in the constellations Aquarius and Pisces are relatively faint. Saturn sets at 2:29 a.m. Eastern Time on Nov. 6 in New York City; the local time will be similar in other locations at similar latitudes, such as Denver, San Francisco, or Chicago.

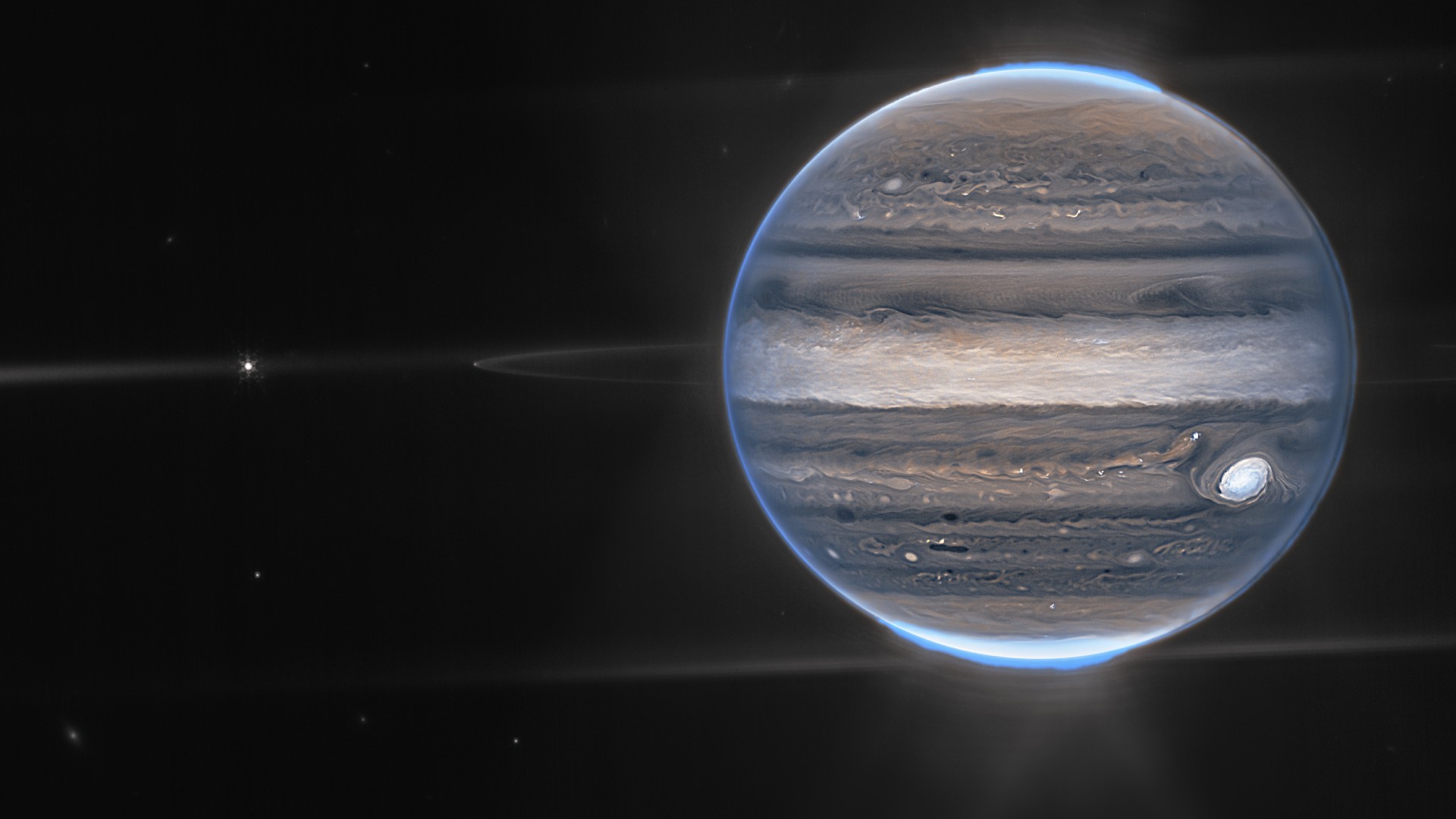

Jupiter follows Saturn, rising at 9:20 p.m. in New York City on the evening of Nov. 5. The planet reaches its maximum altitude at 4:41 a.m. on Nov. 6, reaching about 70 degrees. Jupiter is accompanied by the stars Castor and Pollux; as it rises, Pollux will be above and to the left of Jupiter and Castor further upwards and to the left; the three objects make a rough line pointing to the horizon.

Just before dawn, Venus rises at 5:15 a.m., but from New York, it will be very close to the horizon by sunrise at 6:32 a.m.; at that point, it will only be 12 degrees high, so to catch it, one will need to have an unobstructed horizon and clear weather.

For Southern Hemisphere observers, Saturn is much higher. In Sydney, Australia, sunset is at 7:26 p.m. local time; by the time the sky gets dark at about 8 p.m., Saturn is 52 degrees above the northeastern horizon. Saturn sets at 3:56 a.m. in Sydney on Nov. 6.

As in the Northern Hemisphere, Jupiter rises after Saturn, at 12:41 a.m. in Sydney on Nov. 6. As the sky appears "upside down" for Southern Hemisphere observers, the stars Castor and Pollux will be below Jupiter; Pollux will be below and to the left and Castor slightly below and to the left of Pollux (as one faces northeast). When Jupiter crosses the meridian in Sydney, it will be lower in the sky than in the Northern Hemisphere; at 5:42 a.m., it will reach 35 degrees above the northern horizon. At that point, the sky will be getting light; the sun rises in Sydney at 5:50 a.m.

Venus rises at 5:13 a.m., and in mid-southern latitudes is so close to the sun as to be effectively invisible; by 5:30 a.m., it is still only about three to four degrees above the horizon and the sky will be getting light enough that it is very difficult to see.

Mars and Mercury will both be lost in the glare of the sun; they will reappear later in November.

Constellations

In early November, the Northern Hemisphere winter constellations are starting to rise in the evening. From mid-latitudes, looking at the full moon at about 9 p.m., one should be able to spot Capella, the brightest star in Auriga the Charioteer, by turning one's attention to the right towards the northeast; Capella will be just below the level of the moon. Below the full moon is Aldebaran, the brightest star in Taurus, the Bull. The moon, Capella and Aldebaran will form a right triangle with Aldebaran at the 90-degree corner.

Looking almost straight up at about 9 p.m., one sees the Great Square, an asterism formed by Pegasus, the legendary Winged Horse, and Andromeda. Andromeda's head, the star Merkab, is the upper left corner of the square, while the other three are Pegasus' wing. Alpha Pegasi, or Merkab, is the lower right corner, while Beta Pegasi, or Scheat, is the upper right. The upper left corner is Algenib, or gamma Pegasi.

By about 10 p.m., one can see Orion above the horizon, with the three stars of the Hunter's belt making a near-vertical line in the east-southeast about 15 degrees above the horizon. The Belt stars are named Alnitak, Alnilam and Mintaka, with Alnitak closest to the horizon. Around the Belt, forming a rectangular shape, are the four stars that mark the Hunter's shoulders and feet. To the left of the Belt is the distinctly orange-red star Betelgeuse, and above and to the right of it is Bellatrix. On the other side of the Belt is Rigel (marking the opposite corner of the box from Betelgeuse) and the last is Saiph, marking Orion's right foot (left from the perspective of an earthbound observer).

Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, rises at 10:36 p.m. on Nov. 5 in New York City, but it doesn't get well above the horizon until about 1 a.m. on Nov. 6, when it is 21 degrees high in the southeast. To the left of Sirius is another bright star, Procyon, which will be to the right and below Jupiter, and recognizable because of its blue-white hue compared to the planet's yellowish cast. Sirius and Procyon are in the constellations Canis Major and Canis Minor, respectively. Both stars are among the sun's nearest stellar neighbors; Sirius is only 8.6 light-years away and Procyon is 11.5 light-years distant.

In mid-southern latitudes, in Santiago, Chile or Sydney, Australia, the sky gets fully dark by about 9 p.m. At that point, one can see the full moon in the northeast. Turning to the right (southwards) and staying close to the horizon, one can see Canopus, the brightest star in Carina, the Ship's Keel, about 15 degrees high. Looking straight up from Canopus, almost two-thirds of the way to the zenith, one encounters Achernar, the star marking the end of Eridanus, the River. Most of the surrounding stars are relatively faint, but in a location with fewer lights, one can see the Phoenix, with its brightest star, Alpha Phoenicis or Ankaa, at an altitude of 75 degrees and almost straight upwards from Achernar.

If one looks due north, one will see the Great Square that marks Pegasus and Andromeda; Saturn will be bright enough that it is a good marker, and if one goes from Saturn straight towards the horizon, the line cuts the Great Square in half. Alpha Andromedae, or Alpheratz, will be the star in the lower right corner, while Scheat is the lower left.

Beaver Moon and other November moon names

While Americans — specifically those in the U.S. and Canada – might call the November full moon the Beaver Moon, such "traditional" names come from the European settler cultures and the Native peoples they came into contact with; most are relatively recent. Among Native people, especially, full moons have had various names for millennia.

The Cree, for example, called it Kaskatinowipisim or "Freeze up Moon." The Cree nation's historic territories are in the Great Lakes region; October and November are when nighttime freezing temperatures become more regular. But further south, the Cherokee adopted the name "Trading Moon" for November, as it was just after many harvests and markets would be active, while southwestern peoples often named the November lunation after harvests.

The KhoiKhoi people in South Africa called the November full moon the Milk Moon, according to the Center for Astronomical Heritage, an organization that works to preserve local astronomical traditions.

In India, the November full moon marks the festival celebrating the birth Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism. This is a public holiday in much of India.

If you hope to snap a photo of the full moon, our guide on how to photograph the moon can help you make the most of the event. If you need imaging equipment, our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography have recommendations to make sure you're ready for the next skywatching target.

Editor's note: If you snap a great photo of the Beaver Moon or any other night sky sight you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a story or image gallery, send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.