'Devil Comet' contains 'strongest evidence yet' that comets delivered water to Earth

Water found on Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks is "virtually indistinguishable" from water found on Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A "devil" comet's water is strikingly similar to the water on Earth, researchers have discovered.

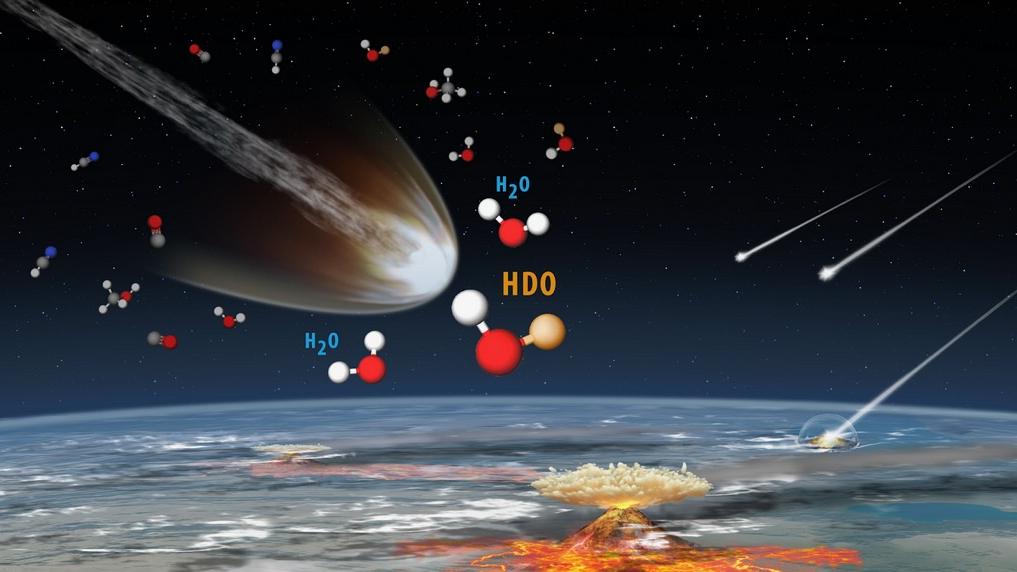

The finding supports the idea that water was brought to our planet through comet impacts, helping set the stage for life to evolve, the team reported Aug. 8 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

"Our new results provide the strongest evidence yet that at least some Halley-type comets carried water with the same isotopic signature as that found on Earth, supporting the idea that comets could have helped make our planet habitable," NASA molecular astrophysicist Martin Cordiner, who led the team, said in a statement.

The researchers made the discovery while observing a comet called 12P/Pons-Brooks — also dubbed the "Devil Comet" — with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF). Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks is a Halley-type comet, a class of comets with orbital periods between 20 and 200 years.

The researchers used ALMA and IRTF data to analyze the ratio of deuterium ("heavy" hydrogen, which has a neutron in its nucleus) to normal hydrogen (D/H) — a "chemical fingerprint" that can be used to trace the water's origins — in the water on Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks. They found that the comet's water is "virtually indistinguishable" from the water on Earth.

This is especially significant because previous measurements of the water on Halley-type comets revealed different D/H ratios, casting doubt on the theory that comets could have brought water to Earth. This new discovery, by contrast, strengthens the theory.

The ALMA observations of Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks mark the first time a comet's water has been mapped in such detail. The team studied both ordinary water (H2O) and "heavy" water (HDO), which contains deuterium. They also analyzed gases in the comet to learn more about its composition.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"By mapping both H2O and HDO in the comet's coma, we can tell if these gases are coming from the frozen ices within the solid body of the nucleus, rather than forming from chemistry or other processes in the gas coma," Stefanie Milam, a project scientist at NASA and co-author of the study, said in the statement.

Space.com contributing writer Stefanie Waldek is a self-taught space nerd and aviation geek who is passionate about all things spaceflight and astronomy. With a background in travel and design journalism, as well as a Bachelor of Arts degree from New York University, she specializes in the budding space tourism industry and Earth-based astrotourism. In her free time, you can find her watching rocket launches or looking up at the stars, wondering what is out there. Learn more about her work at www.stefaniewaldek.com.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.