Where did Earth get its water? It was sucked up from space, new theory says

The theory could have important implications for the search for life outside the solar system.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

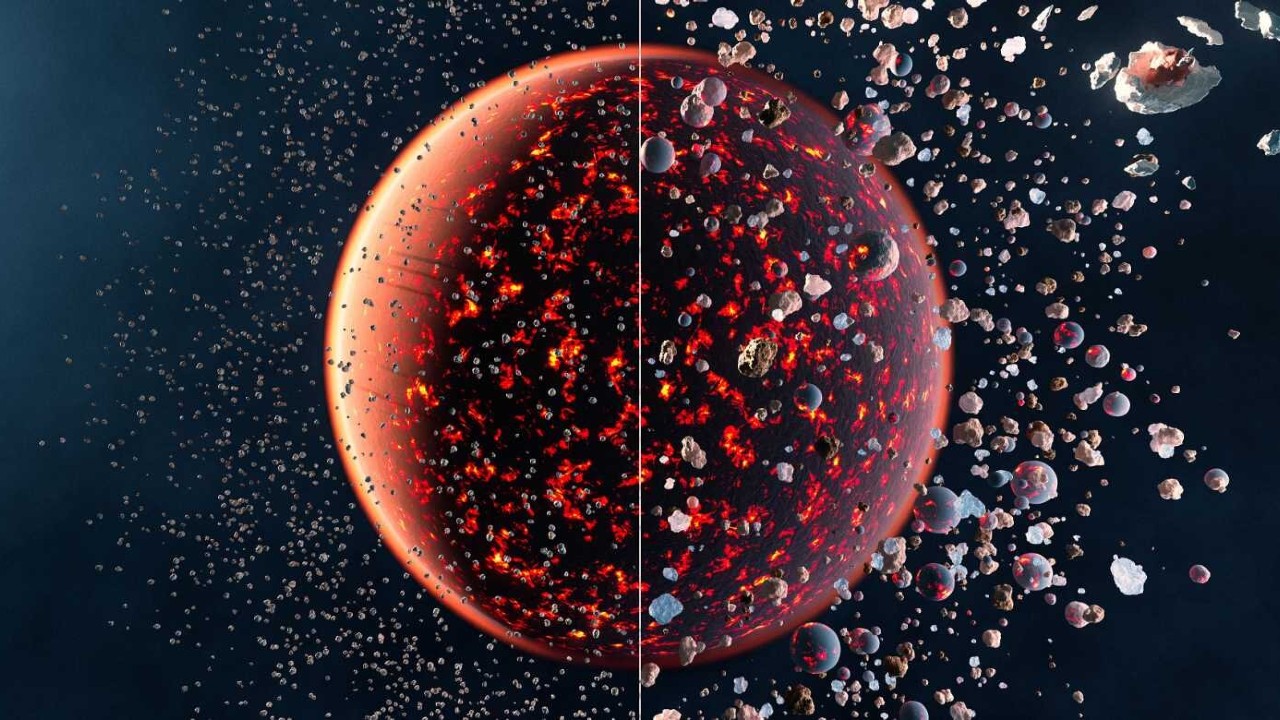

Earth may have formed much more rapidly than previously believed after born as tiny millimeter-sized pebbles that accumulated over a period of just a few million years.

The new theory also implies that rather than water being delivered to Earth by icy comets, this vital ingredient for life is present on our planet due to our young planet thirstily sucking up water from its space environment. The theory could have important implications for the search for life outside the solar system, indicating that watery and habitable planets around other stars may be more common than currently theorized.

The new theory put forward by the team suggests that around 4.5 billion years ago when the sun was an infant star surrounded by a disk of gas and dust, known as a proto-planetary disk, tiny particles of dust would be quickly sucked up by forming planets once they reached a certain size. In the case of the infant Earth, this "vacuuming up" of disk material ensured our planet was supplied with water.

"The disk also contains many icy particles. As the vacuum cleaner effect draws in the dust, it also captures a portion of the ice," team member and Ph.D. student at the Centre for Star and Planet Formation, University of Copenhagen, Isaac Onyett, said. "This process contributes to the presence of water during Earth's formation, rather than relying on a chance event delivering water 100 million years later."

Related: Planet Earth: Everything you need to know

"People have debated how planets form for a long time," University of Copenhagen geochemist and a member of the team behind the theory, Martin Schiller, said in a statement. "One theory is that planets are formed by the gradual collision of bodies, progressively increasing their size over 100 million years. In this scenario, the presence of water on Earth would need a sort of chance event."

One example of such a chance event would be the bombardment of the planet with water-dropping icy comets during the end stages of its formation.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If that is how Earth was formed, then it is pretty lucky that we have water on Earth," Schiller said. "This makes the chances that there is water on planets outside our solar system very low."

The team arrived at their new theory by using silicon isotopes as a gauge to measure the mechanisms of planet formation and the timescales involved. Examining the composition of isotopes in over 60 meteorites and planetary bodies, the researchers were able to establish a connection between rocky planets like Earth and other bodies in the solar system.

The knowledge accumulated by the scientists led them to theorize that with the reliance on chance diminished, there is an increased possibility that other planets have abundant water.

"This theory would predict that whenever you form a planet like Earth, you will have water on it," team member and Globe Institute professor Martin Bizzarro said. "If you go to another planetary system where there is a planet orbiting a star the size of the sun, then the planet should have water if it is in the right distance."

The research is described in a paper published on Wednesday (June 14) in the journal Nature.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.