Yerkes Observatory: Home of Largest Refracting Telescope

Reference Article: Facts about the Yerkes Observatory and Yerkes Telescope.

Yerkes Observatory, in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, houses the largest refracting telescope ever built for astronomical research, with a main lens that's 40 inches (1.02 meters) in diameter.

The observatory is a facility of the University of Chicago and is housed in an ornate Romanesque-style building located on a 77-acre park-like site near Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, about a two-hour drive northwest of downtown Chicago. It opened in 1897 and was closed to almost all activity in 2018.

The Yerkes refracting telescope was gigantic for its time, with a main tube that's 60 feet long (18 m). A refracting telescope is one of the two main types of astronomical telescopes. A refractor has the familiar spyglass design, which operates by gathering light through a large lens at one end of a long tube and focusing the light on an eyepiece, camera or other instrument at the opposite end. (The other type of telescope is the reflector, which uses a large mirror to gather light.) Including lenses, plus the usual attachments and other parts, the complete moving portion of the Yerkes telescope weighs 20 tons.

Building the observatory

In 1892, George Ellery Hale, a University of Chicago professor, learned that America's premier telescope lens maker, Alvan G. Clark, had a pair of optically flawless glass disks, 42 inches (1.07 m) in diameter — perfect for the heart of the world's largest refracting telescope, but it would cost a pretty penny. With the help of William Rainey Harper, the University of Chicago president, Hale approached Charles T. Yerkes, a wealthy Chicago businessman, about funding a new, prestigious observatory, according to the University of Chicago Chronicle. Yerkes had financed Chicago's electric railway system years earlier.

Hale and Harper explained to Yerkes that the new observatory would house a telescope that would beat the Lick Observatory's 36-inch refractor telescope for largest in the world. Yerkes was intrigued by the idea of having his name attached to something that would be the biggest in the world.

"I don't care what the cost, send me the bill," Yerkes told journalists at the time. "I will spend a million dollars to lick the Lick." A few weeks later, Yerkes "exploded with rage" when told that the "bare necessities" for his observatory would cost $285,375 (about $8 million today), according to an article in the Boone County Journal. Nonetheless, Yerkes paid the bill.

Hale consulted a group of distinguished astronomers to select an observatory location free of pollution from smoke and electric lights, yet within 100 miles (161 kilometers) of Chicago, to keep a strong link with the university's main campus. A Chicago real estate speculator offered an expanse of land on the shores of Lake Geneva that fit the bill.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To build the telescope, the university engaged the same team that had built the Lick instrument: Alvan Clark & Sons for the lenses, and the Warner & Swasey Co. of Cleveland for the tube and mounting.

The observatory design

The dome housing the big telescope is 90 feet (27 m) in diameter, according to a pamphlet published by the observatory in 1920. The wooden floor surrounding the pier that supports the telescope is 75 feet (23 m) across and can be raised or lowered by an electric elevator so that astronomers can reach the eyepiece end of the telescope whether it is pointed high or low in the sky.

The observatory opened with a two-day dedication ceremony in October 1897 and served as the home of the University of Chicago's astronomy and astrophysics department until the 1960s.

From the beginning, Yerkes Observatory was designed to be more than a telescope in a dome; it was a comprehensive laboratory for astrophysical research. By 1920, the observatory had three additional telescopes whose capabilities complemented those of the big refractor, as well as an array of laboratory instruments for analyzing light and measuring photographs.

Science at Yerkes

Yerkes Observatory has contributed to numerous scientific discoveries throughout the 20th century. Here are a few highlights:

- In the observatory’s early years, astronomer Frank Schlesinger developed the technique of estimating star distances by taking photographs of the same stars at six-month intervals with the big refractor. He then measured star positions on the photos with a special microscope, looking for any change between one photo and another. Measuring this tiny shift, called parallax, is the most reliable way to measure a star's distance.

- William van Altena built on Schlesinger’s work in the 1970s, using electronic photometers in conjunction with early photographic plates to measure shifts in star positions using the same telescope.

- Edwin Hubble worked as a graduate student at Yerkes from 1914 to 1917, using the reflecting telescope at Yerkes to photograph faint nebulae for his doctoral dissertation. He found surprising brightness changes in the object now known as Hubble's Variable Nebula, or NGC 2261.

- In the 1980s, Kyle Cudworth compared photographs of star clusters taken with the 40-inch telescope more than 80 years apart to measure the motions of stars within the clusters. This information was a key to estimating the distances to the clusters.

Astronomers at Yerkes were also responsible for founding the American Astronomical Society and the respected Astrophysical Journal.

In more recent years, astronomers at Yerkes developed the HAWC (High-resolution Airborne Wideband Camera) to fly on NASA's SOFIA (Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy) aircraft as well as the ARC Echelle Spectrograph, an instrument designed to precisely measure many wavelengths of light simultaneously, for the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico.

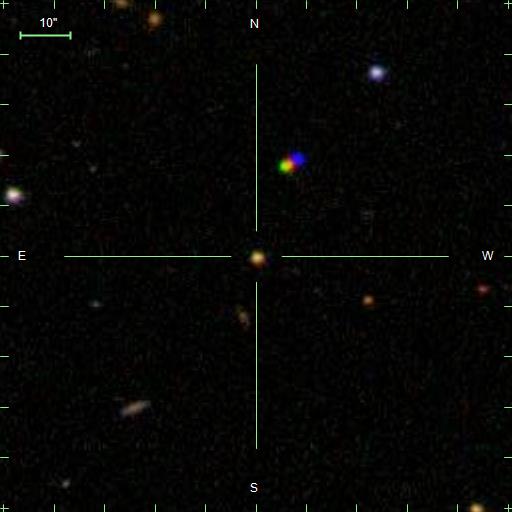

Among the treasures at Yerkes are 170,000 glass photographic plates taken with the 40-inch refractor and the other telescopes starting in the early 1900s and continuing through the century. Astronomers can review this collection for parallax measurements, or any other research that might make use of a photograph of a particular area of the sky as it appeared years ago. Historical parallax work done at Yerkes helped prepare for the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, a multiyear project using a telescope in New Mexico to map the locations of millions of galaxies outside our Milky Way.

Yerkes Observatory closes its doors

In its later years, as research moved to newer telescopes, Yerkes turned to education. April Whitt, an educator based at the Adler Planetarium in the 1990s, recalled helping students from Chicago observe the motions of Jupiter's moons through the giant refractor. "They were so excited to see one of the moons pass behind Jupiter, then come back out on the other side a while later," she said.

One notable education project of Yerkes' later years was Project SEE (Space Exploration Experience) for students who are blind or visually impaired. The program included lessons on infrared light, which no one can see. A memorable experience for the students was to look through the 40-inch refractor and have the light of a star or planet fall on their retina, regardless of their degree of sight or blindness, a University of Chicago news release said.

But after 120 years in operation, the University of Chicago ceased operations at Yerkes on Oct. 1, 2018. The university's research in observational astronomy shifted to facilities worldwide and in space, according to a March 2018 announcement from the university. Observations at Yerkes no longer contribute to the university's research mission, and most education and outreach activities formerly based at Yerkes were moved to the university's Hyde Park campus in Chicago.

However, the observatory's doors aren't closed forever. "The University will continue to occasionally operate the telescopes at Yerkes to ensure the Observatory can continue to be used for research and education, and the large collection of glass photographic plates will continue to be available to researchers by appointment via the department of Astronomy and Astrophysics," the university's physical sciences division said on its website.

The university said that it is continuing discussions with interested parties, including residents of Williams Bay and descendants of Charles T. Yerkes, searching for long-term stewards of the observatory.

Additional resources:

- Find out more about existing Yerkes Observatory education programs on the Yerkes Outreach webpage.

- Watch: "Inside the World's Largest Refractor at Yerkes Observatory," from Explore Scientific.

- Check out archived images of the Yerkes Observatory and images captured by the Yerkes telescope on the University of Chicago's Photographic Archive.

Steve is a former contributor to Space.com in the coverage areas of stars, exoplanets, and constellations. He's an author, podcaster, and retired Planetarium Director at Rochester Museum & Science Center where he was employed for 28 years and responsible for content and scheduling of the venue's Planetarium astronomy shows. Other duties included adapting still and moving images, music and sound, narrating shows, and leading selection and scheduling of all film and laser shows. His book, Sky to Space: Astronomy Beyond the Basics with Comparisons, Ratios and Proportions was published in 2017.