Earth Causes Asteroid-Quakes

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

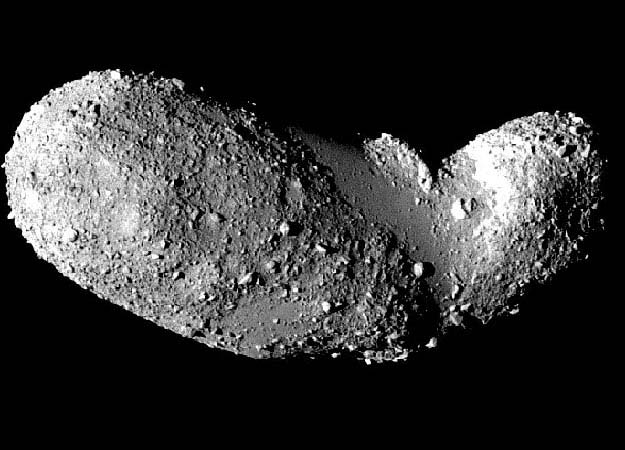

Asteroids may want to think twice before they swing too close to Earth. A new study has found that our planet?s gravity can cause seismic tremors, or asteroid-quakes, if the space rocks stray too close.

This process could explain why many space rocks orbiting nearby appear pristine, as if they were covered in a new and clean surface, researchers said.

Normally, asteroids are weather-beaten, their top coats of rock made dirty and reddened by the onslaught of charged particles streaming off the sun during up to 4 billion years or more of wandering the solar system.

"Any part of the surface that?s facing into the sun is hit by the solar wind, which damages the mineral grains and turns them red," said the study?s lead researcher Richard Binzel of MIT. "An analogy is a sunburn."

Like a sunburn on your skin, the reddening of an asteroid is only skin deep, with fresher material lurking just beneath the sun-drenched surface of the space rock, he added.

But when asteroids approach the Earth, our planet's gravity may induce small quakes that shake up the space rocks, causing the weathered pebbles on their surface to turn over, revealing their cleaner undersides. Asteroids are thought to be more like piles of rubble loosely clung together, than solid chunks of rock, which means even a small tremble could displace surface material.

"All of the particles that got reddened are going to flip over and you're going to have new material that's fresh now out facing the sun," Binzel told SPACE.com. "So it's going to change the color of the asteroid from red to a brighter gray."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The idea has been suggested before, but now Binzel and his colleagues have finally found observational evidence that it's happening.

The researchers observed 95 asteroids in the vicinity of our planet, called near-Earth asteroids (NEAs). They used a process called spectroscopy to determine their colors, to see if they were weathered or fresh, and then combined this data with measurements of the NEAs' orbital histories.

Of the 20 fresh, pristine-looking asteroids in their sample, each had traveled close to Earth ? within the distance from the Earth to the moon ? in the past 500,000 years.

"So we put two and two together and found that asteroids that come very close to the Earth have very fresh undamaged surfaces, and so something about coming close must have resurfaced them," Binzel said. "The simplest explanation is that the bodies got shaken up as they came close."

The scientists detail their results in the Jan. 21 issue of the journal Nature.

Planetary scientist Clark Chapman of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., who was not involved in the research, said that this finding is "observational proof" that asteroids are transformed by the gravitational pull of the Earth.

"The correlation between NEA colors and near-Earth passes is excellent," Chapman wrote in an accompanying essay in the same issue of Nature.

The finding could not only help understand the colors of asteroids, but also how they are made. The researchers plan to use their idea to predict what will happen when the asteroid Apophis passes near Earth in 2029.

It should "shake, rattle, and roll as it goes by," Binzel said. "If we can establish some instruments in orbit or in its surface, listening to and decoding these creaks and groans will tell us how potentially hazardous asteroids like Apophis are put together."

- Video - Killer Asteroids and Comets

- NASA Needs More Money to Hunt Killer Space Rocks

- Images - Asteroids

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.