Hubble Telescope Photographs Jupiter Impact Site

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

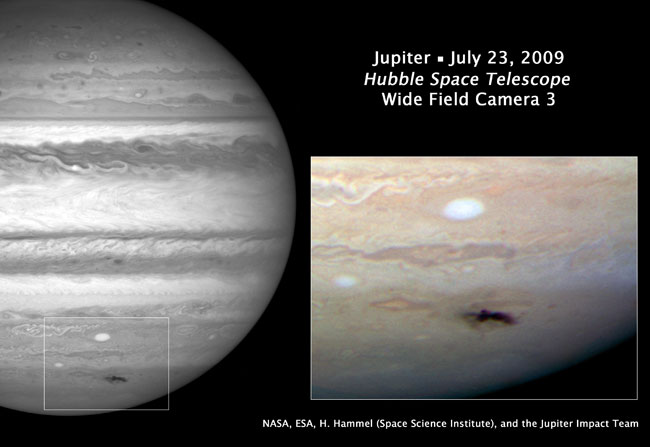

The unexpectedimpact of some space object with Jupiter, creating a dark bruise in the gasgiant?s atmosphere, proved a tempting enough target for scientists to put ahold on testing out the revamped Hubble Space Telescope and use its new camerato capture an image of the rare event.

The plan,first reported by Spaceflight Now, was carried out yesterday so thatastronomers could use the 19-year-old Hubble's unique capabilities to get animage of the spot, probably caused by a comet, before too many days had passed since the impact andJupiter's atmosphere distorted the shape.

The newHubble image, released today, shows a lumpiness to the debris plume caused byturbulence in Jupiter's atmosphere. The image is a natural color image of Jupiter in visible light.

"Itwas important for Hubble to get an early look," said Hubble spokesman RayVillard.

The darkspot was firstnoticed by chance by amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley in Australia on Sunday, July 19.

The bruiseis near Jupiter's southern pole and is about the size of the Pacific Ocean,according to one astronomer's estimates.

The featureis reminiscent of the 1994 impact of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Whileastronomers don't know for sure what impacted Jupiter this time around,"the best guess is that it's a comet," the reasoning being thatcomets cross Jupiter's orbit while asteroids rarely do, Villard said.

While othertelescopes (including the Keck IItelescope and the Gemini Observatory, both in Hawaii) have trained theireyes on the spot in recent days, it was important for Hubble to take a lookbecause "it's the sharpest at visible wavelengths," Villard toldSPACE.com. Hubble also has capabilities to look at ultraviolet wavelengths,which can show details of the impact debris that has been tossed high intoJupiter's atmosphere.

"Itreally was incumbent upon us to join with the other telescopes," Villardsaid.

Hubble wasin the middle of testing and calibration of its new instruments, installed byastronauts during a service mission in May. Hubble managers decided that theimpact event was rare enough and important enough to pause testing to get alook.

Recent glitcheshave delayed the commissioning of some instruments, but the new Wide FieldCamera 3 is working fine.

"It'snot fully calibrated, but it doesn't mean we can't take pictures," Villardsaid.

With theHubble images complementing other telescope's efforts, astronomers hope tolearn more about the dark spot and the impactor that caused it.

With thedata astronomers have from the Shoemaker-Levy 9 impact, they can guess at somefeatures of the likely comet. It is estimated to have been no bigger than halfa kilometer and likely had thousands of times the energy of the Tunguska impacthere on Earth, which generated a huge explosion over Siberia in 1908,flattening an area as big as a large city.

Hubble isslated to take more images of the new impact spot in the coming days, to helpastronomers track its progress. In between pictures, the Hubble team should beable to resume testing and calibration of the camera.

- Video - The Jupiter Crash of Shoemaker-Levy 9

- Images ? Hubble's Latest Views of the Universe: Part 1, Part 2

- Jupiter's New Bruise Big As Pacific Ocean

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.