Mystery of Saturn's Watery Moon Solved

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

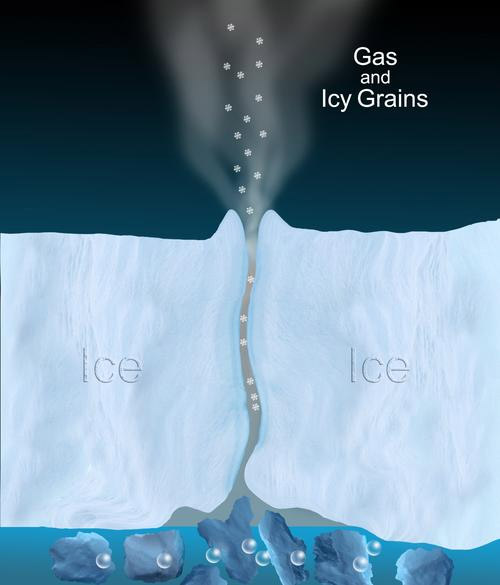

Cosmicsprinklers that spurt misty jets from cracks along Saturn's sixth largest mooncould hint at a vast watery lake hidden beneath the icy shell of Enceladus.

In 2005,NASA's Cassini spacecraft revealed giantgeysers of ice grains and water vapor shooting from the south pole ofEnceladus. But how the geysers formed and the source of the ice crystals hadremained a mystery until now. New research, detailed in the Feb. 7 issue of thejournal Nature, provides a clear view of the processes beneath themoon's crust that yield the handful of geysers.

The resultsreveal there must be water beneath the moon's surface and also support the ideathat Enceladus'geysers are the source of Saturn's E-ring, a faint circle of tiny ice anddust particles.

"SinceCassini discovered the water vapor geysers, we've all wondered where this watervapor and ice are coming from," said researcher Juergen Schmidt of theUniversity of Potsdam, Germany, who is a team member on Cassini's Cosmic DustAnalyzer. "Now, after looking at data from multiple instruments, we cansay there probably is water beneath the surface of Enceladus."

Theresearchers are uncertain how large the water reservoir is. "It might be aglobal ocean. It might be just a small lake," Schmidt said.

The finding makes Enceladusone of only four moons in our solar system thought to harbor liquid water.The other watery worlds are Jupiter's moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.While Saturn is home to 60 identified moons, Enceladus is the first to showsigns of liquid water.

Beneaththe ice

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Schmidt andhis colleagues relied on Cassini data on the ice grains along with computermodels to arrive at their conclusion about the water.

Here's whatthey think is happening:

Hiddenbeneath Enceladus' icy exterior is a lake with a temperature of about 32degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees Celsius). At these relatively warm temperatures(for the frigid outer solar system) liquid water, ice and water vapor mingle.The vapor moves upward through channels in the ice toward openings at themoon's surface. Upon reaching the vacuum conditions of space found within thechannels and cracks, the vapor expands and cools leading to the formation ofice crystals.

Both themodel and the Cassini observations suggest the vapor in the plumes moves atroughly the same speed as a supersonicjet, about 650 to 1,100 mph (300 to 500 meters per second). That's nearlydouble the speed needed to escape Enceladus' gravity.

The icegrains, however, trek along at a much slower rate. The researchers say as theice particles zigzag through crooked cracks in the ice, they ricochet off thewalls and lose speed. The water vapor moves unimpeded through the crevasses andboosts the frozen particles to carry them upward.

Even with apush from the vapor stream, only about 10 percent of the ice particles haveenough energy to break through Enceladus' gravity. The remaining slowpokes fallback to the moon's surface.?

Saturn'sring

The escapedice crystals' liberty is short-lived, however. Scientists think the crystalsare recaptured by Saturn?s gravity and coalesce to form the planet?s E-ring.

"Theseparticles in the E-ring hit other satellites in the system or the main rings ofSaturn or they hit Enceladus itself," Schmidt told SPACE.com."So they are born at Enceladus, but they also have sinks so they diesomewhere, and that gives them balance which is more or less steadytoday."

The heatsource that drives the interior melting of the ice is still unknown, but now researchersthink they know the conditions needed to drive Enceladus' plumes.

"Ifvapor temperature is too low, then the gas density is too small to push thegrains out and we would not see such large amounts of particles," Schmidtsaid. "Therefore, we believe that at the site of evaporation, we must havetemperatures near the melting point of water."

The nextEnceladus flyby is set for March, when the Cassini spacecraft will reach itsclosest approach of a mere 30 miles (50 kilometers) from the surface. As thespacecraft moves farther away to an altitude of about 124 miles (200kilometers), it will pass through and sample Enceladus' plumes.

- Video: Enceladus, Cold Faithful

- Image Gallery: Cassini's Latest Discoveries

- Cassini Special Report