Geysers Gush from Cracks in Saturn's Moon

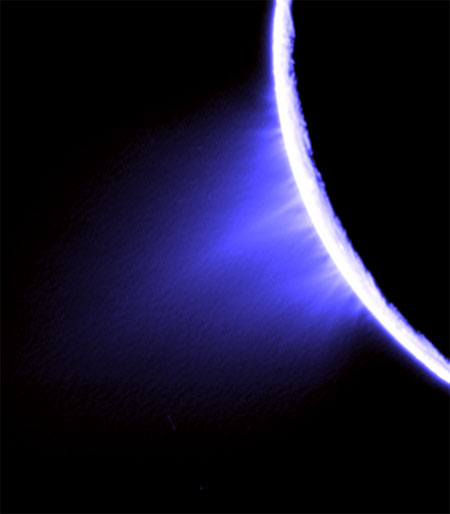

Slushy geysers on Saturn's moon Enceladus erupt from fractures clustered around a hot spot at the satellite's south pole, scientists have now confirmed.

Using NASA's Cassini spacecraft, researchers recorded the location of jet events on Enceladus for two years. They found that the most prominent jets emanated from hot spots along four cracks, or "tiger stripes," on the moon's surface called Alexandria, Cairo, Baghdad and Damascus.

The monikers come from a naming convention created during the days of the Voyager spacecraft, which required features on Saturnian satellites be named after the myths and epics of the world. The fissures on Enceladus were named after cities in the Arabian story collection, "One Thousand and One Nights."

The discovery, detailed in the Oct. 11 issue of the journal Nature, is the first to directly link the tiger stripes and the jets.

"We suspected that the jets were coming from the fractures … but this is now definitive proof," said study team member Carolyn Porco, leader of Cassini's imaging team at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

The finding also provides new observational constraints for computer modelers attempting to simulate the geyser's underlying mechanisms, Porco said, and could help determine whether a vast liquid ocean—and possibly life—lies beneath Enceladus' crust.

An active moon

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Geological activity on Enceladus was only confirmed about two years ago, when Cassini's infrared camera detected an anomalous hot spot on the moon's south pole and revealed that pale blue "veins" on the moon's surface were actually deep chasms spewing a mixture of liquid water, ice and organic compounds into space.

Scientists now think Enceladus' slushy ejecta are the source of Saturn's tenuous E-ring, and that other Saturnian moons passing through this ring are coated in the reflective substance, making them unusually bright.

Recently, scientists have theorized the geysers might be powered by the grinding of ice sheets against one another and the periodic opening and closing of gaps on the moon's surface.

Both mechanisms were thought to be driven by a process called tidal heating. Because Enceladus' path around Saturn is elliptical, it is pulled unevenly by the planet's gravity at different points along its orbit. This creates a bulge on the moon's surface that grows and shrinks depending on the moon's distance from Saturn.

The repetitive motion generates friction and heat, which scientists suspect drives the tiger stripes to open and close.

The new findings are generally consistent with the geyser mechanism models, except for one major discrepancy involving the tiger stripe Baghdad, said study team member Joseph Spitale, also of the Space Science Institute.

"They didn't predict almost any heating on [Baghdad], and we found our strongest sources there," Spitale told SPACE.com.

Future models will have to take Baghdad's activity into account, the researchers say.

The discrepancy "means that the people who are doing these kinds of models need to go and see if they can't tweak their parameters to try and match what we're observing," Porco said.

The go-to moon

Enceladus is only one of a handful of bodies in our solar system known to be geologically active, and, in Porco's opinion, is the go-to place to answer questions about astrobiology.

"Mars has been a candidate for a long time, but even the guys who study Mars will tell you—if they are being at all objective about this—that chances are there are no living organisms on Mars … unless you go to the poles," she said.

Porco thinks Enceladus also has a leg up on Jupiter's satellite Europa, another leading contender in scientists' eyes as a life-harboring world, because many of the suspected requirements for life have already been confirmed on Enceladus.

"We've flown through the plumes. We've measured the presence of organics. We already know there's access heat" on Enceladus, Porco said. "The only outstanding question is, do these jets derive directly from liquid water or not?"

- Special Report: Cassini's Mission to Saturn and its Moons

- Encore For Enceladus! Saturn Moon Ripe For Astrobiology Exploration

- VIDEO: Enceladus-Cold Faithful

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.