Sun's Baby Twin Spotted

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

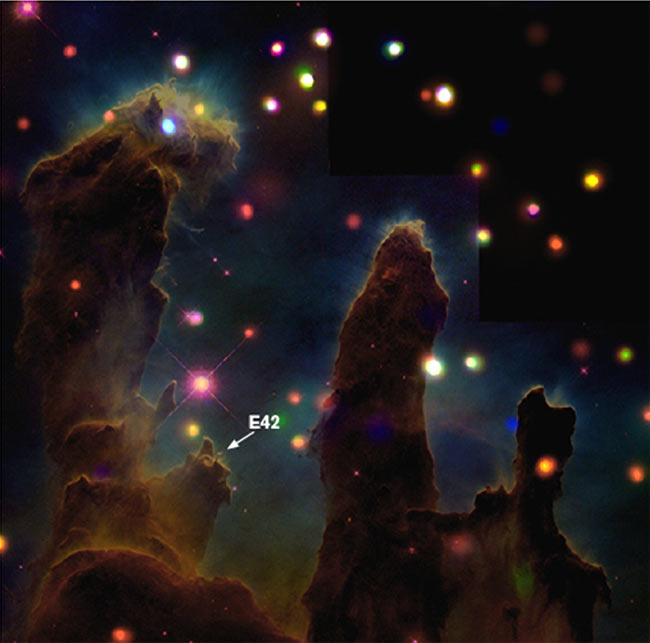

Likened toa stellar womb, the iconic soaring space towers known as the Pillarsof Creation have revealed an embryo of an infant star that could developinto a twin of our Sun.

Astronomersimaged the babystar in what they consider the earliest stages of development ever detectedfor this type of object.

Hiding outon a nodule that juts out from the left pillar, "E42" is known as an evaporatinggas globule (EGG). An EGG is a dense pocket of interstellar gas that forms an"egg" from which a star emerges. This particular EGG has the same mass as the Sunand appears to be maturing in a violent environment matching the one thought tohave produced Earth's life-giving star.

"We thinkthis is a very, very early version of our own Sun," said Jeffrey Linsky ofJILA, a joint institute of the University of Colorado, Boulder and the NationalInstitute of Standards and Technology.

Starfactory

Linsky andhis colleagues used NASA's ChandraX-ray Observatory to peek at the embryo inhabiting the EagleNebula.

Locatedabout 7,000 light-years from Earth,the Eagle Nebula is a star-forming region within the Pillars of Creation wherenearby gas and dust feed the birth of new stars. Many of the stars churned outhere now reside just outside the pillars, where their ultraviolet emissionssculpt out the structures.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The newbieis one of 73 EGGs discovered in this celestialcastle in 1995 with the Hubble Space Telescope(HST). While 11 of the gas globules are thought to contain infant stellarobjects, only four are massive enough to form a star. Of those, E42 is the onlyone that boasts a Sun-sized mass.

"The fourproto-stars that we have identified on the edges of the pillars are probablythe youngest stars ever imaged by astronomers," Linsky said.

While theX-ray capability let the team view about 1,100 hot, maturestars in the nebula, the EGGswere not emitting any X-rays due to their infantilenatures.

Instead thescientists viewed visual and infrared emissions to pinpoint E42 [image]and its neighbors.

"Theresults indicate young, evolving stars like E42 have not yet developed themagnetic structures needed to produce X-rays," he said.

Brutalbirth

In additionto its mass, E42 is maturing in an environment similar to what astronomersthink produced Earth'sSun, 5 billion years ago. Unlike a nurturing womb, however, Earth's Sun seemed to form from clouds of dust andgas that got seared by ultraviolet radiation and pummeled with shock waves fromat least one supernovaexplosion.

"The Sunwas likely born in a region like the Pillars of Creation because the chemicalabundances in the solar system indicate that a supernova occurred nearby andcontributed its heavy elements to the gas of which the Sun and the planetsformed," Linsky explained.

In January2007, a French astronomy team observed a glowing cloud of scorched dust next tothe pillars, suggesting that about 6,000 years ago a supernova explosion toppledthe stellar structures. The newly described proto-star E42 apparentlyemerged unscathed.

"My guess isthat the shock wave from the supernova may have been far enough away so thatE42 and some of the other stars may have survived," said Linsky. "But I guesswe will have to wait another thousand years or so to get the answer."

The studyis published in the Jan. 1 issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Video: Supernova: Destroyer/Creator

- Video: Supernovas: Beacons in the Night

- Ancient Solar Observatory Discovered

- Images: The Many Faces of the Sun

- Images: Sun Storms