Clouds, But No Water, Detected On Distant Planet

The most detailed analysis ever of light from the atmospheres of planets outside our solar system has turned up no evidence of water but possible hints of clouds, scientists said today.

"We're getting our first sniffs of air from an alien world," said David Charbonneau of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "And what we found surprised us. Or more accurately, what we didn't find surprised us."

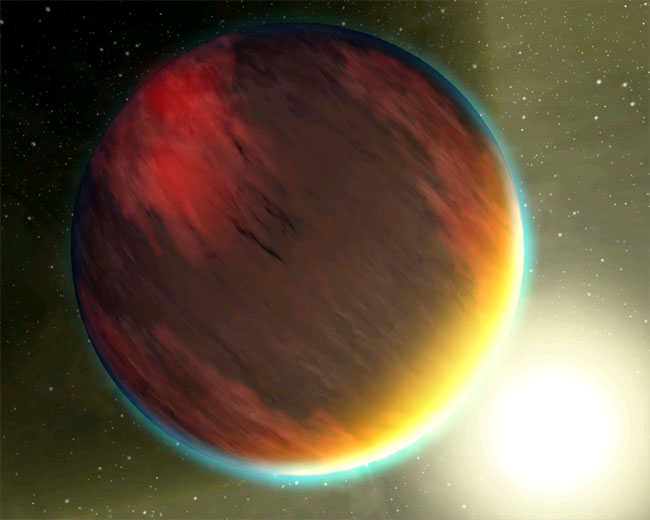

Using NASA's infrared Spitzer space telescope, Charbonneau and his team studied a so-called hot Jupiter planet [image] called HD 189733b. Hot Jupiters are large gas giants like our own Jupiter, but they orbit so close to their parent stars that they are extremely hot. A year on HD 189733b is only 2.2 Earth days long and the planet is a broiling 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit. HD 189733b is located about 60 light years away in the constellation Vulpecula.

The technology to tease apart the light from a distant planet and star is not available yet, so scientists use a different trick [image].

"Instead of separating the [light from the planet and star] in space, we separate them in time," Charbonneau explained. "We wait for the planet to pass out of view behind the star, and then we measure the brightness of the star very carefully. Then we gather data at any other time, when both the planet and star are in view. If you take their difference, then whatever's left over has got to be the light from the planet."

In 2001, Charbonneau's team used the Hubble Space Telescope and a different technique to detect small amounts of sodium in the atmosphere of an exoplanet. The discovery marked the first time that astronomers had ever detected the atmosphere of a planet orbiting another star.

"Now we're able to look over many different colors," Charbonneau explained. "In the past, we had to target this one wavelength and this one feature due to this one atom. It was exciting at the time, but these data that we're presenting now are much more informative."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The study by Charbonneau's team is detailed online in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters .

No signs of water

After obtaining the light spectrum of HD 189733b, Charbonneau's team scanned it for tell-tale "fingerprints" of specific molecules.

Theory predicts that hot Jupiters contain large amounts of water vapor and also methane. Planets form from the same material as their stars, and stars like the one HD 189733b orbits contain many different elements, including hydrogen, helium, carbon and oxygen. Therefore, these elements must also be present in the makeup of planets around the star.

On hot Jupiters, there is "so much hydrogen and oxygen that they will react and turn into a water molecule. At those pressures, it's inevitable," Charbonneau told SPACE.com.

Similarly, carbon and hydrogen are thought to combine on hot Jupiters to form methane.

However, to the researchers' great surprise, no signs of either of these two molecules were detected.

"We expected that the planet would appear fainter, due to absorption by water molecules in the atmosphere," Charbonneau said. "That was a very strong prediction and made by many different groups that had tried to predict what these atmospheres would be like."

High Clouds and hidden water

Results obtained by another team suggest the water and methane are present, but hidden by thick clouds.

A team led by Jeremy Richardson of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center also used Spitzer to obtain the spectrum of HD 209458b, another hot Jupiter located about 150 light years away in the constellation Pegasus.

The spectrum Richardson's team obtained also showed no signs of water or methane, but it did reveal hints of silicate-molecules containing silicon and oxygen. On Earth, silicates are a major component of rocks. On hot Jupiters, under scorching temperatures, silicates would exist as tiny dust grains that could coalesce to form clouds.

The study by Richardson's team is detailed in the Feb. 22 issue of the journal Nature.

"It might explain why we don't see the water," Charbonneau said. "If there is a high cloud deck, it would prevent us looking down into the atmosphere."

Mark Swain, a researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the leader of another team which independently analyzed HD 209458b, agrees that there are probably clouds on the hot Jupiter but is not convinced the clouds are made of silicate.

"In our view, the silicate case is not proven," Swain said. "We find [the spectrum] to be consistent with featureless thermal emissions from dust."

"I think it's certainly true that we don't understand the details of what we see," Richardson said. "The feature that we see is real. Is it possible that something else could cause that feature? Maybe. Maybe a different element. I think it's probably silicates."

Still exciting

Further studies of HD 189733b, HD 209458b and other hot Jupiters are planned to help clear up the mystery.

"Right now, it's a puzzle," Charbonneau said. "With a few more puzzle pieces, the picture should become clearer."

Despite not finding evidence for water on the two hot Jupiters, the ability to do so is itself exciting, said Alan Boss, a planet-formation theorist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington who was not involved in any of the studies.

"This is the first time that we have been able to look for water in the atmosphere of a distant extrasolar planet," Boss said in an email interview. "The NASA mantra for looking for life on Mars is 'follow the water' and the same holds true for extrasolar planets. Looking for water will be one of the main goals of the Terrestrial Planet Finder (TPF), and this new result just whets our appetite for what is to come when TPF flies."

- Distant Planet is Half Fire, Half Ice

- Giant Planets Pack Supersonic Winds

- Astronomers Discover Bundle of Extrasolar Planets

- First Detection Made of an Extrasolar Planet's Atmosphere

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.