Second Mountain Range Rises from Pluto's 'Heart' (Photo)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

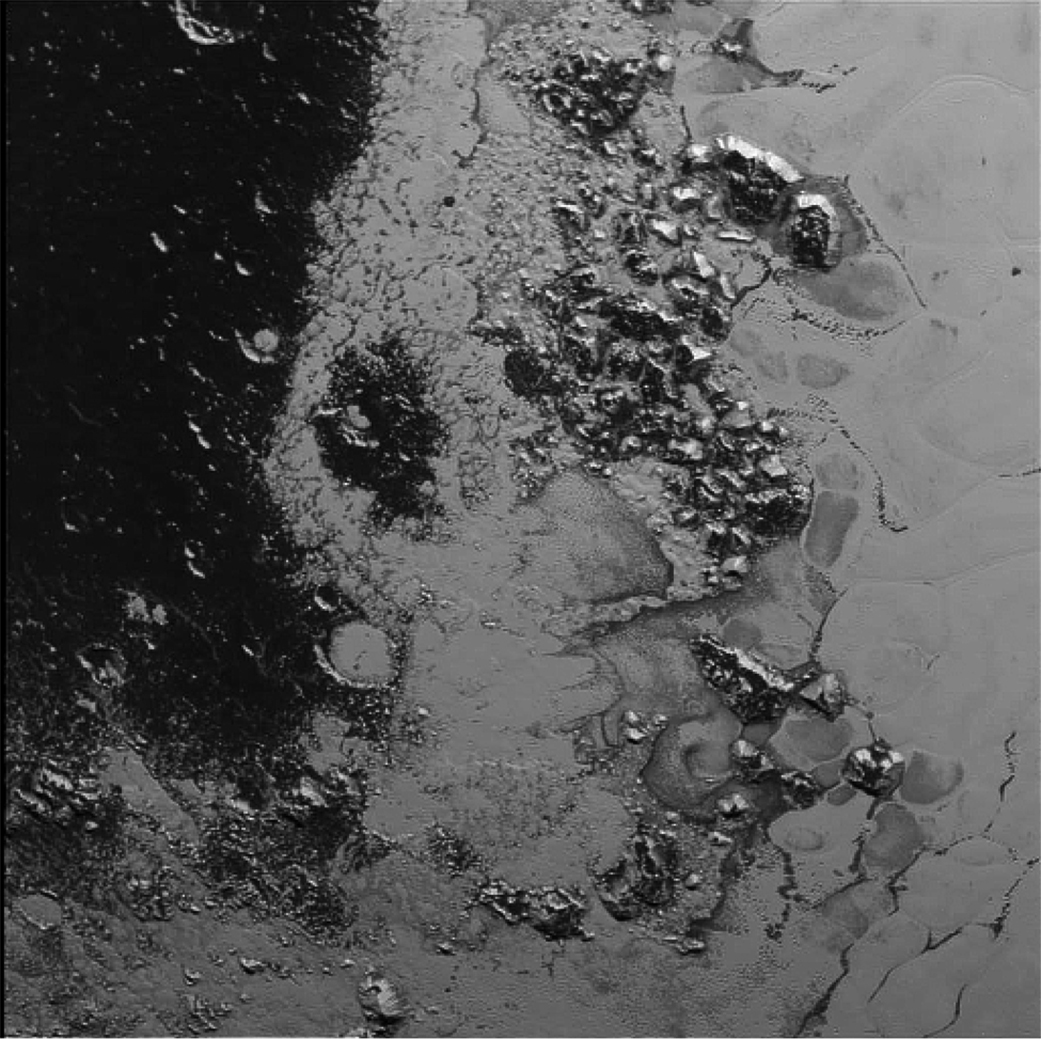

Pluto has a big heart — big enough to accommodate at least two sets of mountains, a new photo from NASA's New Horizons spacecraft reveals.

New Horizons has spotted a second mountain range inside Tombaugh Regio, the 1,200-mile-wide (2,000 kilometers) heart-shaped feature that mission team members named after Pluto's discoverer, Clyde Tombaugh.

This newfound range rises up to 1 mile (1.6 km) above Pluto's frigid surface, making it comparable in height to the Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States, NASA officials said. Tombaugh Regio's other known mountain range, by contrast, is more similar to the tall and jagged Rocky Mountains, topping out at more than 2 miles (3.2 km) in elevation. [New Horizons' Pluto Flyby: Complete Coverage]

The newly discovered range lies just west of the ice plains known as Sputnik Planum and is 68 miles (110 km) northwest of the taller mountain range, which mission scientists are calling Norgay Montes after Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, who along with Edmund Hillary completed the first-ever ascent of Mt. Everest, in 1953. (Tombaugh Regio, Norgay Montes and other such names remain informal monikers until they're officially approved by the International Astronomical Union.)

The new photo, which New Horizons captured during its historic Pluto flyby on July 14, shows a startling complexity of terrain within Tombaugh Regio, researchers said.

"There is a pronounced difference in texture between the younger, frozen plains to the east and the dark, heavily cratered terrain to the west," Jeff Moore, leader of New Horizons' geology, geophysics and imaging team, said in a statement today (July 21) upon the photo's release.

"There's a complex interaction going on between the bright and the dark materials that we're still trying to understand," added Moore, who's based at at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The lack of craters on Sputnik Planum suggests the icy plains are extremely young in geological terms — 100 million years or less, mission team members have said. But the darker terrain to the west is probably several billion years old.

Features as small as 0.5 miles (0.8 km) wide are visible in the new photo, which New Horizons took from a distance of 48,000 miles (77,000 km). But the spacecraft zoomed to within just 7,800 miles (12,500 km) of Pluto's surface on July 14, so even more spectacular images of the dwarf planet should be coming down to Earth in the future.

All of New Horizons' close-approach data should be in researchers' hands in compressed form by the end of 2015, while it may take another year to get the complete flyby dataset down to Earth, team members have said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.