NASA Eyes Crew Deep Sleep Option for Mars Mission

A NASA-backed study explores an innovative way to dramatically cut the cost of a human expedition to Mars -- put the crew in stasis.

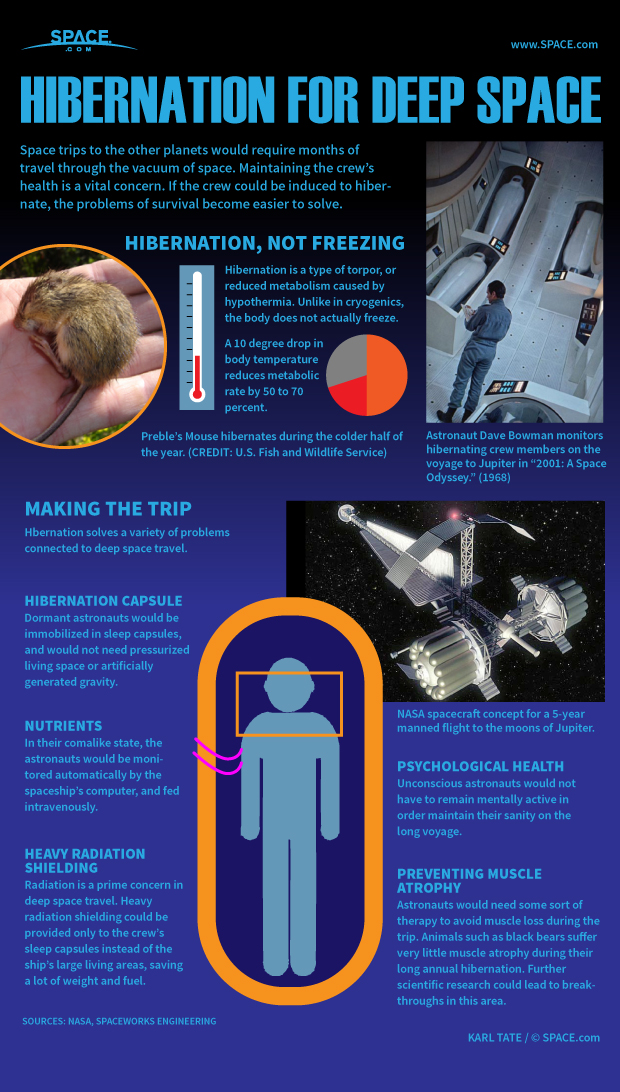

The deep sleep, called torpor, would reduce astronauts' metabolic functions with existing medical procedures. Torpor also can occur naturally in cases of hypothermia.

ANALYSIS: Private Mars Mission in 2018?

"Therapeutic torpor has been around in theory since the 1980s and really since 2003 has been a staple for critical care trauma patients in hospitals," aerospace engineer Mark Schaffer, with SpaceWorks Enterprises in Atlanta, said at the International Astronomical Congress in Toronto this week. "Protocols exist in most major medical centers for inducing therapeutic hypothermia on patients to essentially keep them alive until they can get the kind of treatment that they need."

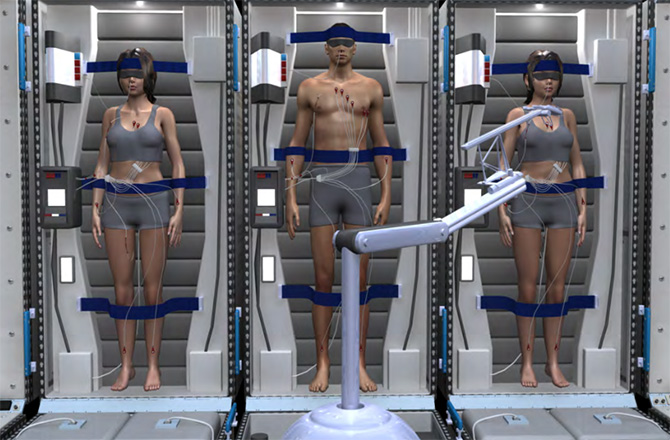

Coupled with intravenous feeding, a crew could be put in hibernation for the transit time to Mars, which under the best-case scenario would take 180 days one-way.

So far, the duration of a patient’s time in torpor state has been limited to about one week.

"We haven't had the need to keep someone in (therapeutic torpor) for longer than seven days," Schaffer said. "For human Mars missions , we need to push that to 90 days, 180 days. Those are the types of mission flight times we’re talking about.”

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

ANALYSIS: Why Extroverts Could Cause Problems on a Mission to Mars

Economically, the payoff looks impressive. Crews can live inside smaller ships with fewer amenities like galleys, exercise gear and of course water, food and clothing. One design includes a spinning habitat to provide a low-gravity environment to help offset bone and muscle loss.

SpaceWorks' study, which was funded by NASA, shows a five-fold reduction in the amount of pressurized volume need for a hibernating crew and a three-fold reduction in the total amount of mass required, including consumables like food and water.

Overall, putting a crew in stasis cuts the baseline mission requirements from about 400 tons to about 220 tons.

"That's more than one heavy-lift launch vehicle," Schaffer said.

This article was provided by Discovery News.

Irene Klotz is a founding member and long-time contributor to Space.com. She concurrently spent 25 years as a wire service reporter and freelance writer, specializing in space exploration, planetary science, astronomy and the search for life beyond Earth. A graduate of Northwestern University, Irene currently serves as Space Editor for Aviation Week & Space Technology.