Galaxy Halos Recycle Interstellar Gas Into Baby Stars

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

How a galaxy evolves from an active star-forming spiral into a passive collection of stars has perplexed astronomers, but a series of new studies may have found the answer inside vast clouds of galactic gas.

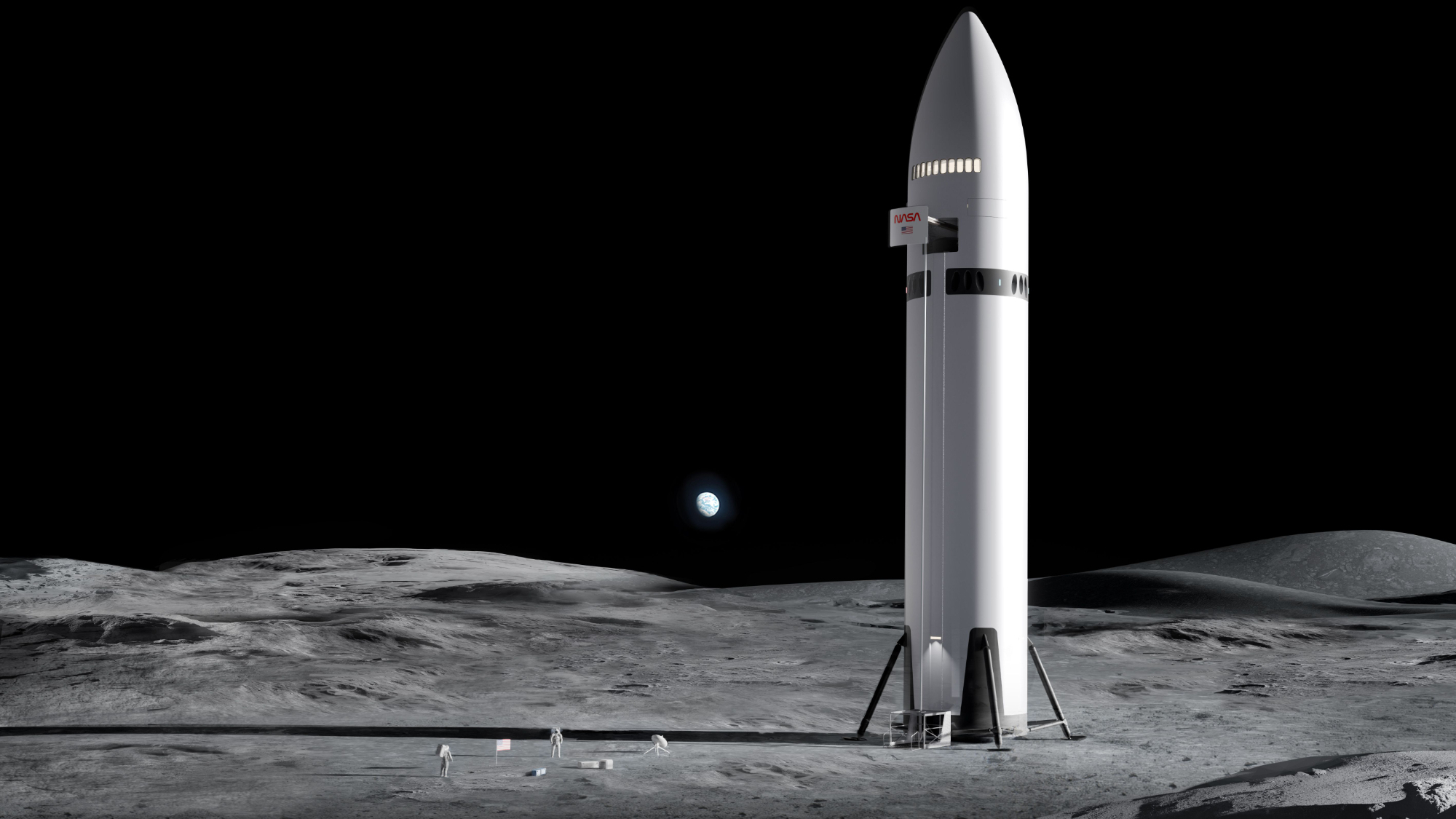

Ejected by dying stars, halos of galactic gas can help fuel the creation of new stellar objects, researchers said. In the new research, one study found that the gas halos dominate the space around spiral galaxies but are significantly smaller around galaxies with little or no star formation. The halos are larger, too, and more metal-rich than anticipated, scientists found.

Three papers, published together in today's (Nov. 17) issue of the journal Science, study the location of these halos, and how gas moves into and out of galaxies.

Recycled content

Astronomers have long known of the existence of galaxy halos, which can be up to 450,000 light-years across. [65 All-Time Great Galaxy Photos]

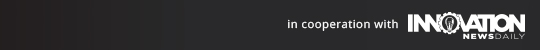

Using the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) on the Hubble Space Telescope, a team led by Jason Tumlinson, of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, searched the halos for oxygen. They then inferred the total amount of heavy elements, and thus the total amount of gas.

The results were surprising.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The amount of oxygen we found requires about a billion solar masses of stars to produce," Tumlinson told SPACE.com. "By almost any measure, that's pretty big."

Because all elements other than hydrogen and helium are formed inside of stars, spreading through space when they explode, this narrows down the origins of most of the gas within the halo.

Most individual explosions won't produce the necessary energy to eject the gas. But a chain of explosions might.

As galaxies merge, the inflow of dust and gas into the new center can set off a sudden blaze of star formation. Because these new stars all form at about the same time, they all die within a few million years of each other, generating a tremendous amount of energy.

Known as a galactic superwind, this force sweeps dust and gas out of the galaxy and into the halo.

Sometimes, the gas falls back into its parent galaxy, where it helps birth new stars. A study of the halo surrounding the Milky Way revealed that it contained enough material to fuel star formation for another billion years.

But if there is enough energy, the galactic superwind can sweep the gas completely out of the galaxy.

Blowin' in the superwind

Todd Tripp, of the University of Massachusetts, studied a single galaxy where most of the material permanently escaped.

"We were able to probe different aspects of these outflows, thanks to the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph on the Hubble," Tripp told SPACE.com. [Amazing Hubble Telescope Discoveries]

The Hubble allowed them to get a more detailed and expansive look at the halos.

"Previous flows have seen clouds but have not been able to trace them out to these distances," Tripp said.

The halo surrounding the galaxy, known as Galaxy 177_9, extends to well over 220,000 light-years. One light-year, the distance light travels in a single year, is about 6 trillion miles (10 trillion kilometers). The Galaxy 177_9 halo was not one of the 42 studied by Tumlinson, but the teams worked closely together.

Tripp's group then calculated the speed of the gas in the halo. To their surprise, the gas was rushing out at speeds of up to 2 million mph (3.2 kph) — fast enough to escape the gravity of the galaxy and break free into space.

"This is one system where it is absolutely clear-cut some of the gas is on its way out and not coming back," Tumlinson said.

Galactic differences

Galaxy mergers bring fresh materials to the table, and can jumpstart star-making. But the new births can also mean death for the system, if the violent explosions kick the needed material out of the system after only a single cycle.

This escape, fueled by starbursts, could help explain how active star-forming galaxies can so quickly become quiescent.

The fact that halos dominate star-forming galaxies seems to provide further evidence of the correlation. As the gas is used up or cast out, the stellar birthrate slows. Both teams intend to examine other systems to see how prevalent these results are.

Galaxy 177_9 is part of a larger study that Tripp is already working on.

"We want to study gaseous envelopes of a wide variety of galaxies of different types."

This will help them determine how widespread features such as the rapid velocity are among the halos. Tumlinson also intends to continue studying halos around more galaxies.

"There's billions of galaxies in the universe, and we were able to observe about 40," he said. "That's a rather small sample."

Studying the size and composition of shells around other spiral and elliptical galaxies should help provide astronomers with more insights into galaxy evolution.

"As long as Hubble lasts, we'll keep pounding away at this."

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky