This Antarctic Meteorite Holds a Tiny Speck of Stardust That's Older Than the Solar System

A tiny speck of stardust, hidden within a meteorite from Antarctica, is likely older than our sun — and was catapulted into our celestial neighborhood by an ancient star explosion that predates the formation of our solar system.

This ancient grain is only 1/25,000 of an inch, sports a "croissant-like shape," and could tell us a thing or two about the origins of our solar system, researchers said April 29 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Using multiple types of microscopes, these researchers peered into the stardust and found that it was made up of a combination of graphite (a form of carbon) and silicate (a salt made up of silicon and oxygen). When the scientists compared this composition with models, they determined that it likely came from a specific type of star explosion called a nova. [Fallen Stars: A Gallery of Famous Meteorites]

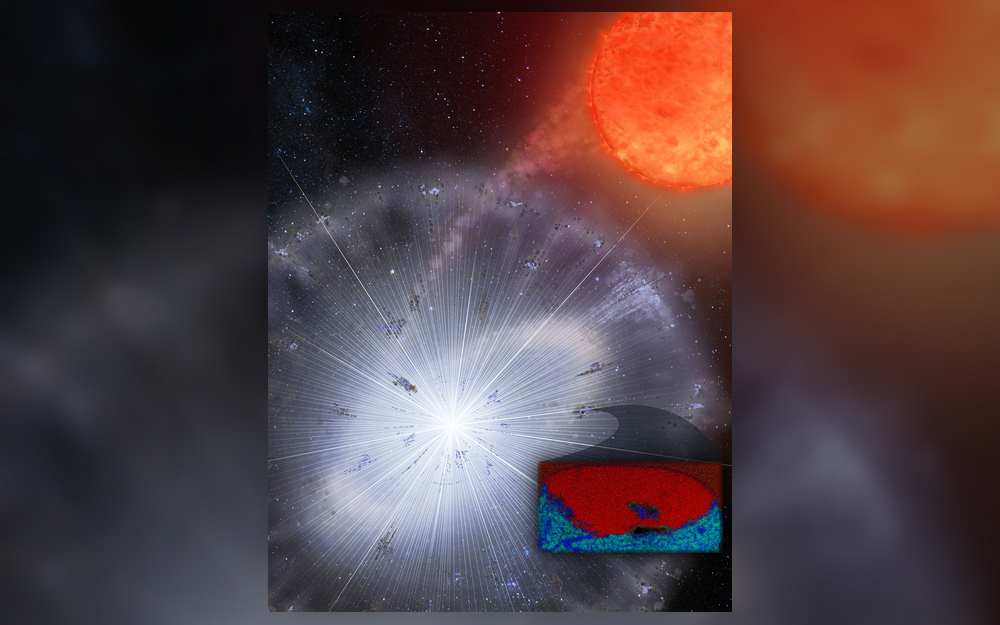

Nova explosions happen in the exchange of energy between an ordinary star and a white dwarf, a star that has burned off most of its nuclear fuel. The white dwarf feeds off the other star, accreting enough new material to reignite itself in powerful outbursts that spew material into space. This is how the sample of stardust, named LAP-149, formed and then made its way through interstellar space to the vicinity of our solar system.

"These stardust grains are like fossilized relics of ancient stars," co-author Tom Zega, an associate professor in the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona told Live Science. What's more, the researchers know that this piece of stardust must have traveled from far away, because it has high levels of a very specific form, or isotope, of carbon (carbon-13). Such high levels are not seen in any object sampled from our solar system, Zega said.

Star explosions throw ingredients into interstellar space, where they eventually serve as the seeds for planets. So, rare finds like this ancient grain could yield insights into how our solar system formed, according to a statement.

The results provide further evidence that both carbon- and oxygen-rich grains that come from nova explosions helped build the solar system. Though the grain was way too small for the researchers to date it, they guessed, based on its composition and the meteorite that it came from, that its at least 4.5 billion years old — around the time our solar system formed.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"These are the ashes of different kinds of stars that have faded or are on their way to fading out of the the universe," Zega said. "Moreover, because we find them preserved inside of meteorites and because we can age date meteorites using radioisotopes, we know they must be older than the meteorite itself." Meteorites like LAP-149 are "very primitive," and are among the "leftovers from after the sun and planets formed," he added.

Zega and the team hope to find and analyze bigger specimens of stardust in the future, which they hope they will be able to date.

In any case, the very existence of this speck of primordial history is amazing, the researchers said. "It's remarkable when you think about all the [events] along the way that should have killed this grain," Zega said in the statement.

- Meteor Crater: Experience an Ancient Impact

- Space Rocks! Photos of Meteorites for Sale

- Space-y Tales: The 5 Strangest Meteorites

Originally published on Live Science.