Sinking ice on Jupiter's moon Europa may be slowly feeding its ocean the ingredients for life

"Most excitingly, this new idea addresses one of the longstanding habitability problems on Europa and is a good sign for the prospects of extraterrestrial life in its ocean."

Jupiter's icy moon Europa may have a previously unrecognized way of delivering life-supporting chemicals to its vast subsurface ocean, according to new research.

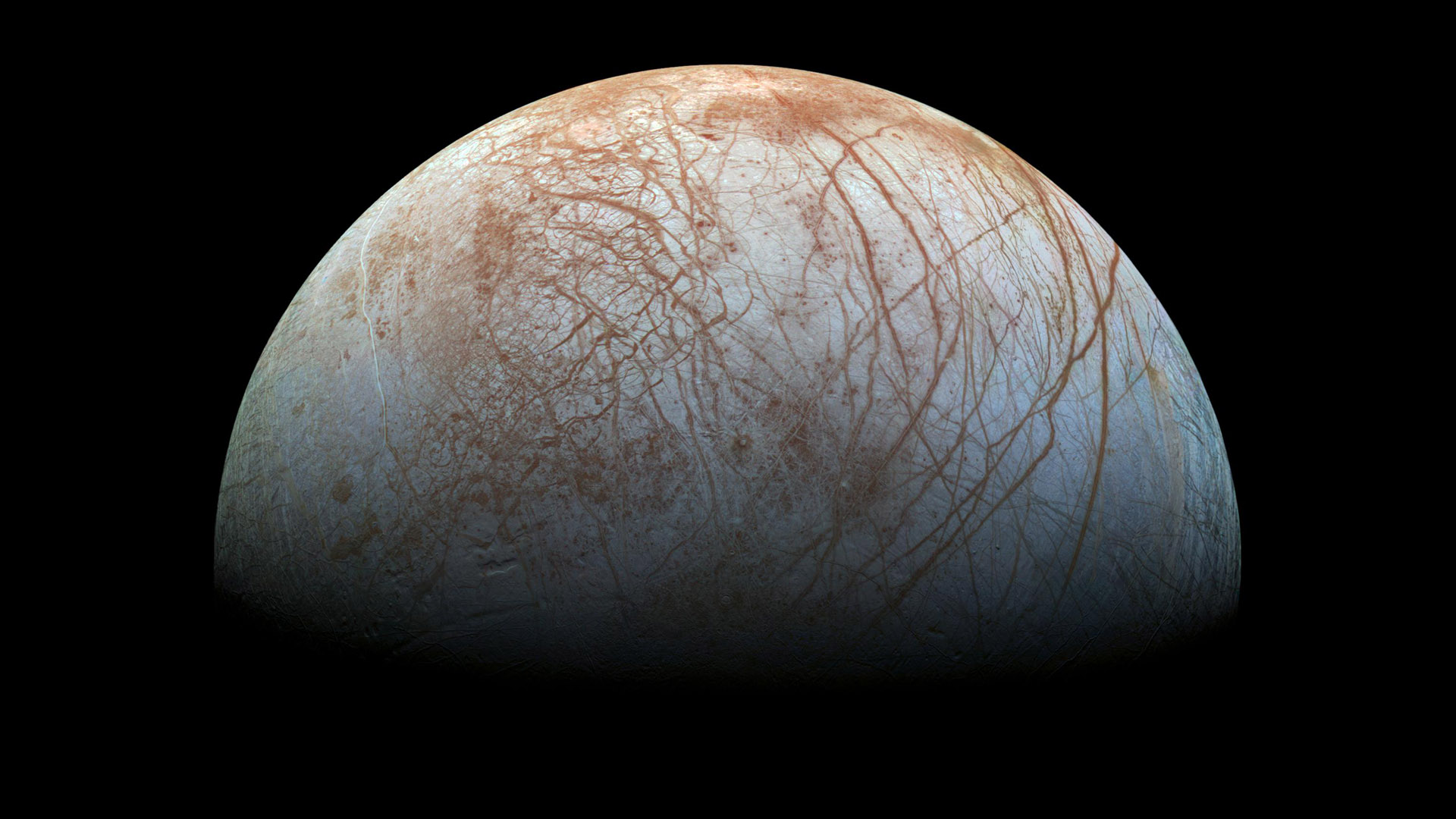

Europa, one of the dozens of moons orbiting Jupiter, has long intrigued scientists as one of the most promising places in the solar system to search for extraterrestrial life, thanks to a hidden global ocean beneath its fractured, frozen surface that may contain twice as much salty water as all of Earth's oceans combined. Unlike Earth, however, Europa's ocean is deprived of oxygen and sealed off from sunlight, ruling out photosynthesis and requiring any potential life to rely on chemical energy instead. A key unanswered question has been how ingredients for that energy — such as life-supporting oxidants created on the moon's surface by intense radiation from Jupiter — could be transported through Europa's thick ice shell to the ocean below. Now, a new study by researchers at Washington State University suggests the answer may lie in a slow but persistent geological process that causes portions of Europa's surface ice to sink, carrying those chemicals downward.

"This is a novel idea in planetary science, inspired by a well-understood idea in Earth science," study lead author Austin Green, now a postdoctoral researcher at Virginia Tech, said in a statement. "Most excitingly, this new idea addresses one of the longstanding habitability problems on Europa and is a good sign for the prospects of extraterrestrial life in its ocean."

Scientists know from images taken during spacecraft flybys that Europa's surface is highly geologically active due to Jupiter's powerful gravitational pull. However, most of this motion appears to occur horizontally rather than vertically, according to the new study, which limits opportunities for surface materials to migrate downward, except during extreme events such as the formation of large fractures.

Additionally, the Jovian moon's near-surface ice is thought to behave as a rigid "stagnant lid," further restricting the delivery of oxidants to the subsurface ocean, the study notes.

Using computer models, the researchers found that pockets of salt-rich ice near Europa's surface can become both denser and mechanically weaker than surrounding, purer ice. Under the right conditions, these denser patches can detach and slowly sink, or "drip," through the ice shell, eventually reaching the ocean below in as little as 30,000 years, according to the study.

The process, known as lithospheric foundering, resembles a geological process on Earth in which portions of the planet's outermost layer sink into the mantle. In 2025, researchers identified this process unfolding beneath the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To test whether a similar mechanism could operate on Europa, Green and his team modeled an ice shell roughly 18.6 miles (30 kilometers) thick under a range of ice shell conditions. In all six scenarios the team examined, surface material within the top 300 meters descends toward the base of the shell, the new study reports.

In some simulations, the sinking began after 1 to 3 million years and reached the base of the shell after 5 to 10 million years. In ice shells that were more heavily damaged or weakened, sinking began after as little as 30,000 years, the study reports.

This occurred for almost any salt content, the researchers say, provided the surface ice experienced at least some degree of weakening.

According to the study, the mechanism "may be an expedient method of transporting surface materials to the underlying Europan ocean."

The moon will be studied in greater detail in the coming years by NASA's Europa Clipper mission. Launched in 2024, the spacecraft is scheduled to arrive in the Jovian system in April 2030 and conduct nearly 50 close flybys of Europa over four years, allowing scientists to assess the depth of its subsurface ocean and further evaluate the moon's potential habitability.

The team's research is described in a paper published on Tuesday (Jan. 20) in The Planetary Science Journal.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.