'A remarkable discovery': Astronomers find 1st exoplanet in multi-ring disk around star

"Discovering this planet was an amazing experience!"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Astronomers have discovered a hungry baby planet gobbling up material around an infant star located around 430 light-years from Earth. The planet has been given the suitably cute name WISPIT 2b.

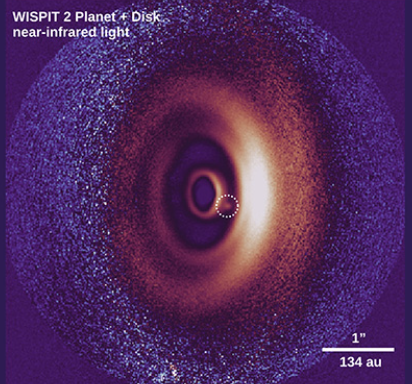

WISPIT 2b is estimated to be a gas giant around the size of Jupiter and around just 5 million years old. If this seems ancient, remember our solar system is around 4.6 billion years old. The extrasolar planet, or "exoplanet," is carving a channel in the planet-forming disk of gas and dust, or "protoplanetary disk," around its young parent star WISPIT 2 like a cosmic Pac-Man as it gathers material.

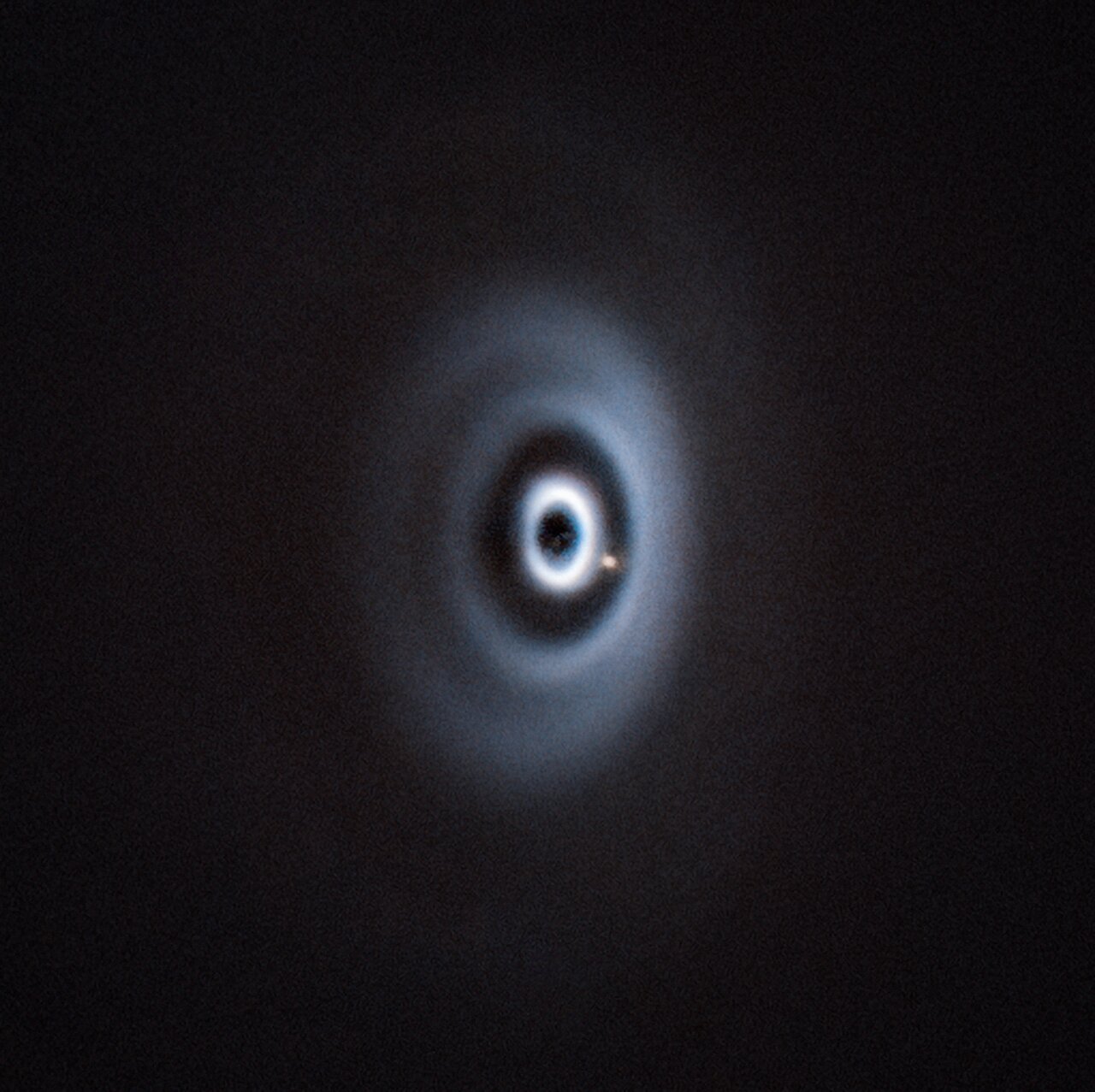

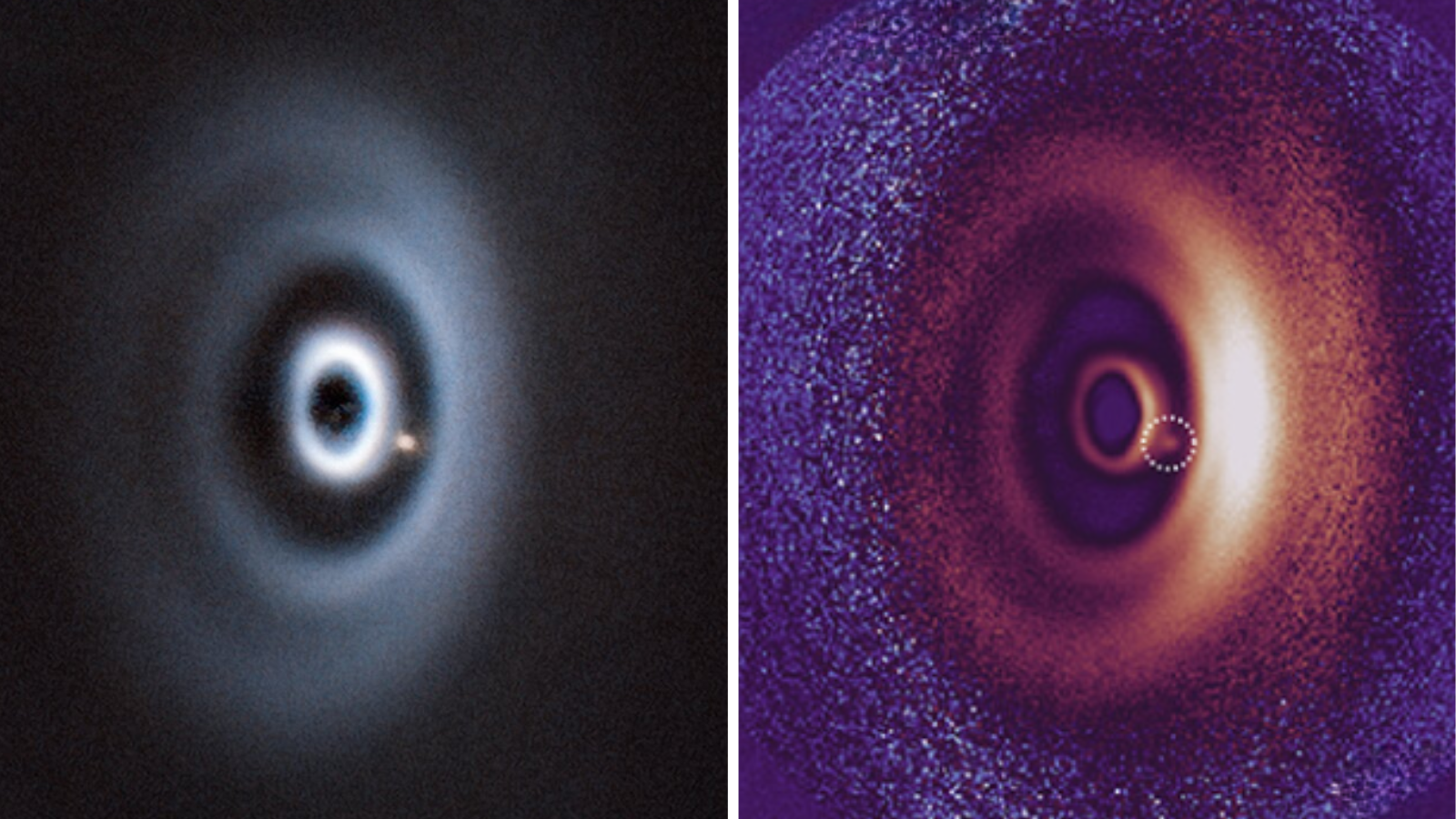

The exoplanet is the first confirmed detection of a planet in a multi-ringed protoplanetary disk, a disk that contains multiple gaps and channels, almost akin to a vinyl record.

Imaged using the Very Large Telescope (VLT) located in the Atacama Desert in Chile, WISPIT 2b is also just the second young planet confirmed around a star that is essentially analogous to a young sun.

This makes the study of WISPIT 2b and its home protoplanetary disk, which is as wide as around 380 times the distance between Earth and the sun, the ideal laboratory to study interactions between planets and disks and the subsequent evolution of such systems.

"Discovering this planet was an amazing experience - we were incredibly lucky," team leader and Leiden University researcher Richelle van Capelleveen said in a statement. "WISPIT 2, a young version of our sun, is located in a little-studied group of young stars, and we did not expect to find such a spectacular system. This system will likely be a benchmark for years to come.”

The team captured an infrared image of the planet sitting in a gap in the disk as they conducted an investigation designed to discover if gas giants on wide orbits are more common around young or old stars. This was possible because the infant planet is still hot and glowing following its formation.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We used these really short snapshot observations of many young stars - only a few minutes per object - to determine if we could see a little dot of light next to them that is caused by a planet," said Christian Ginski, lecturer at the School of Natural Sciences, University of Galway. "However, in the case of this star, we instead detected a completely unexpected and exceptionally beautiful multi-ringed dust disk.

“When we saw this multi-ringed disk for the first time, we knew we had to try and see if we could detect a planet within it, so we quickly asked for follow-up observations."

A separate crew of researchers from the University of Arizona imaged WISPIT 2b in optical light. These observations revealed that WISPIT 2b is still gathering matter.

"Capturing an image of these forming planets has proven extremely challenging, and it gives us a real chance to understand why the many thousands of older exoplanet systems out there look so diverse and so different from our own solar system," Ginski added. "I think many of our colleagues who study planet formation will take a close look at this system in the years to come."

Ginski added that the team was fortunate to have these incredible young researchers on the case of WISPIT 2b, adding that this will be the first of many breakthroughs to come from the next generation of astrophysicists.

"The planet is a remarkable discovery. I could hardly believe it was a real detection when Dr. Ginski first showed me the image," team member and University of Galway MSc student Jake Byrne said. "It's a big one - that's sure to spark discussion within the research community and advance our understanding of planet formation."

The team's research was published across two papers published on Tuesday (Aug. 26) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.