NASA's Found a Weird, Rectangular Iceberg in Antarctica

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

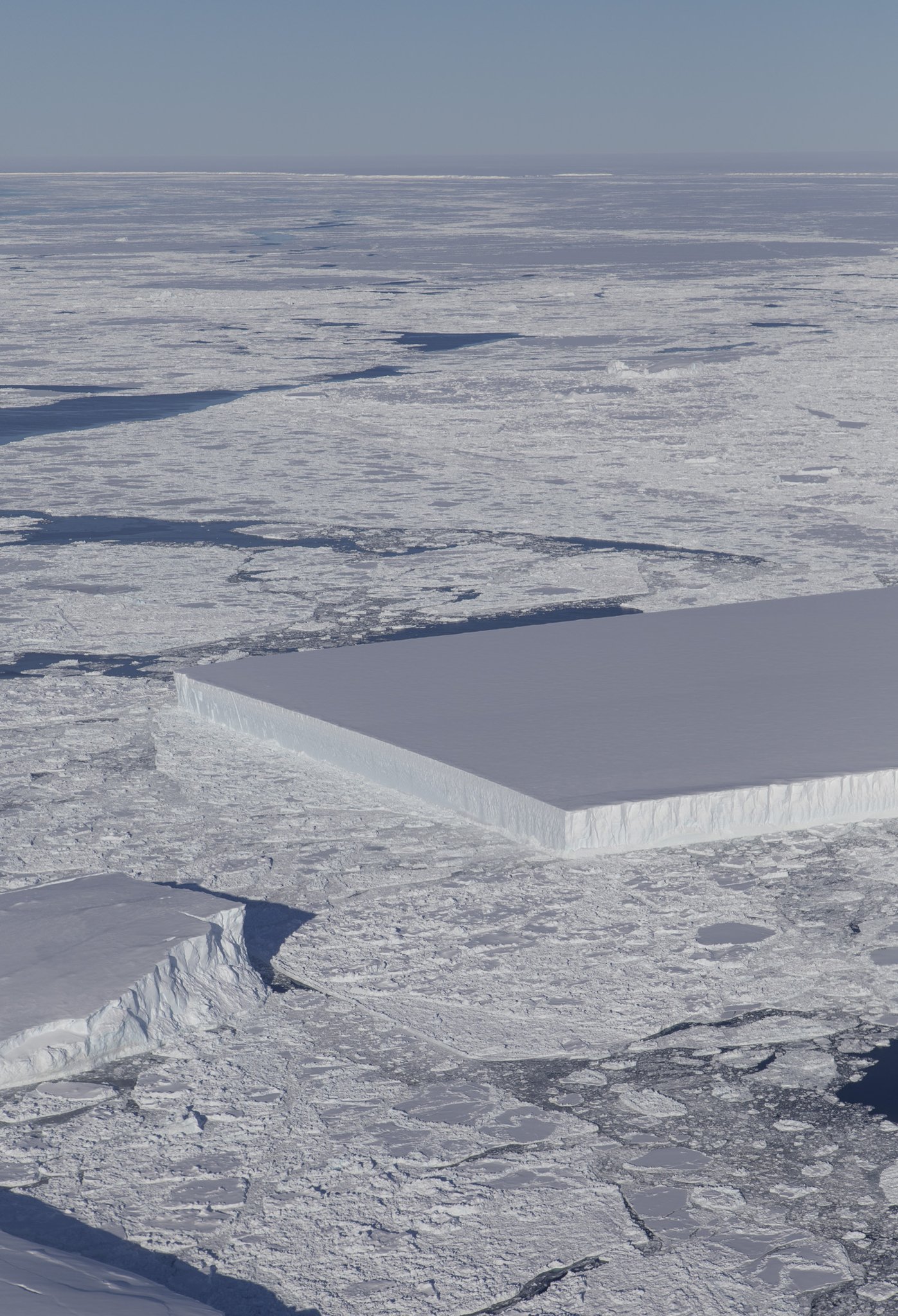

Look at that iceberg. It's beautiful. Perfectly rectangular. An object of near geometric perfection jutting into a polar sea of the usual squiggly, chaotic randomness of the natural world. It calls to mind the monolith from "2001: A Space Odyssey."

But, unlike the monolith from that very weird movie, this iceberg was not deposited on this world by space aliens. Instead, as Kelly Brunt, an ice scientist with NASA and at the University of Maryland, explained, it was likely formed by a process that's fairly common along the edges of icebergs.

"So, here's the deal," Brunt told Live Science. "We get two types of icebergs: We get the type that everyone can envision in their head that sank the Titanic, and they look like prisms or triangles at the surface and you know they have a crazy subsurface. And then you have what are called 'tabular icebergs.'" [In Photos: Huge Icebergs Break Off Antarctica]

Tabular icebergs are wide and flat, and long, like sheet cake, Brunt said. They split from the edges of ice shelves — large blocks of ice, connected to land but floating in the water surrounding iced-over places like Antarctica. This one came from the crumbling Larsen C ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula.

Tabular icebergs form, she said, through a process that's a bit like a fingernail growing too long and cracking off at the end. They're often rectangular and geometric as a result, she added.

"What makes this one a bit unusual is that it looks almost like a square," Brunt said.

It's difficult to tell the size of the iceberg in this photo, she said, but it's likely more than a mile across. And, as with all icebergs, the part visible above the surface is just the top 10 percent of its mass. The rest, Brunt said, is hidden underwater.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the case of tabular icebergs, she said, that subsurface mass is usually regular-looking and geometric, similar to what's visible above. This iceberg looks pretty fresh, she said — its sharp corners indicate that wind and waves haven't had much time to break it down.

But despite the berg's large mass, Brunt said, she wouldn't advise going on a walk on its surface.

"It probably wouldn't flip over," she said.

The thing is still much wider than it is deep, after all. But it's small enough to be unstable and crack up at any moment.

So, it's probably best to marvel at the thing from a distance.

Originally published on Live Science.

Rafi wrote for Live Science from 2017 until 2021, when he became a technical writer for IBM Quantum. He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School of journalism. You can find his past science reporting at Inverse, Business Insider and Popular Science, and his past photojournalism on the Flash90 wire service and in the pages of The Courier Post of southern New Jersey.