Moon to Hide a Beehive

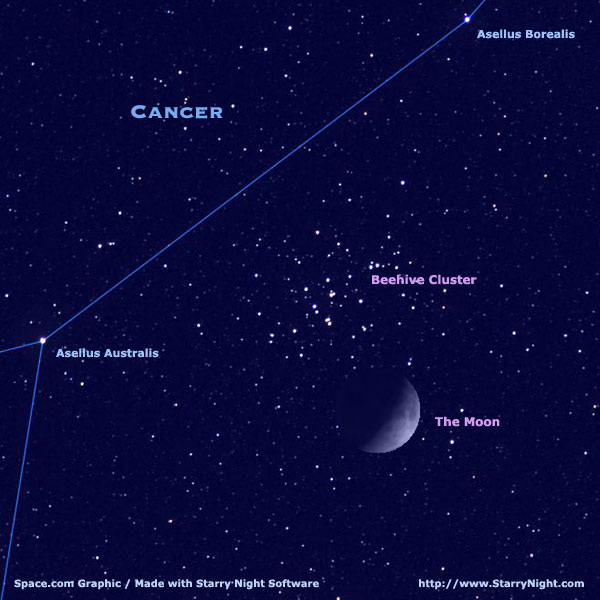

If theweather is clear in your area on Saturday, May 10, be sure to check out the fatcrescent moon in the southwestern sky with binoculars or a small, low powertelescope as darkness falls. On that evening, the moon will be positionedwithin the dim constellation of Cancer, the Crab.

One of myastronomy mentors, the late Dr. Ken Franklin of New York's Hayden Planetarium,used to refer to Cancer as "the empty space" in the sky. Indeed, it'sthe least conspicuous of the 12 zodiacal constellations and quite frankly,aside from being in the zodiac, it's probably noteworthy only because itcontains one of the brightest star clusters in the sky. It is Praesepe, betterknown as the Beehive Star Cluster, which contains a myriad of small stars.

For much ofthe United States and southernmost Canada, the moon will already be in theprocess of crossing in front of part of this star cluster as darkness falls.Astronomers call this an occultation, in essence an "eclipse" of a celestialobject — in this case the star cluster — by the moon.

Little Mist ... Big Star Cluster

Cancer's big star cluster is known formally as Messier 44.The name "Praesepe" extends back to ancient times and refers to amanger: a trough or box used to hold food for animals (as in a stable), mostlyused in raising livestock.

Interestingly, Praesepe was also used in medieval times as aweather forecaster. It was one of the very few clusters that were mentioned inantiquity. Aratus (around 260 BC) and Hipparchus (about 130 BC) called it the"Little Mist" or "Little Cloud." But Aratus also noted thaton those occasions when the sky was seemingly clear, but the "LittleMist" was invisible, that this meant that a storm was approaching.

Of course, we know today that prior to the arrival of anyunsettled weather maker, high, thin cirrus clouds (composed of ice crystals)begin to appear in the sky. Such clouds are thin enough to only slightly dim the sun,moon and brighter stars, but apparently just opaque enough to hide a dimpatch of light like Praesepe.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Praesepe remained a mysterious patch of light until Galileodirected his crude telescope toward it in the year 1610, and saw that it was acluster of stars too dim to be separately visible to the unaided eye.

Binocularsshow up dozens of its stars, while large telescopes reveal about 200. The starsare spread over an area roughly three times the apparent diameter of the moon.It appears so large because of its relative closeness to us at a distance ofabout 580 light years away, closer to us than all but a few clusters.

As for how the cluster's more popular name,"Beehive," evolved, it may have been that some anonymous person onceexclaimed, when he saw so many tiny stars revealed in an early telescope,"It looks like a swarm of bees!" So "Beehive" is arelatively "new" title, dating back to perhaps the early 17th century.

Occultation night

As darkness falls across North America on May 10, the moonwill already be advancing upon the star cluster. If you live in southern Canada or the northern United States, the moon will interact with little more than with a glancingblow, skirting the cluster's very lowest edge and covering only a few stars.Over the central part of the country, the moon will pass across the lower thirdof the cluster, while viewers across the southern states will see the moon hideits lower half.

The moon will be a waxing crescent, 38 percent illuminated.As it moves from west-to-east across the star background any member of the starcluster that happens to be in its path will disappear behind the moon's darkedge, and later emerge from behind the bright edge.

Binoculars or a small low-power telescope will greatlyenhance the view, not only of the cluster's individual stars, but also of thephenomenon known as earthshine;the moon appearing as a wide arc of yellowish-white light enclosing a ghostlybluish-gray ball. This is sunlight reflected from Earth illuminating the nightside of the moon, making its whole disk visible. Here is one of nature'sbeautiful sights and fits the old saying, "the old moon in the new moon'sarms."

Times for when the moonwill appear to be covering the greatest portion of the cluster:

- Canadian Maritimes — wait until nearly midnight, Atlantic Daylight Time.

- Eastern Time Zone — around 11:20 p.m.

- Central Time Zone — 10:10 p.m.

- Mountain states, evening twilight will still be in progress when maximum coverage occurs at around 8:55 p.m.

- Arizona (which does not observe daylight time) — 7:55 p.m.

- Pacific States — at or before sunset; by the time the sky becomes sufficiently dark, the moon will have moved off to the east, leaving most of the stars in the cluster behind.

What to call it?

Praesepe or Beehive? The final choice is yours.

From my own personal viewpoint, I prefer to refer to thecluster by its older moniker, Praesepe, for this simple reason: Two nearbystars, Gamma and Delta in Cancer, bracket Praesepe to the north and south respectivelyand have been known for some 20 centuries by their respective names AsellusBorealis and Asellus Australis — the Aselli, or northern and southern ass colts— feeding from their manger (Praesepe).

Although some might commonly associate these animals asstubborn, they actually have a keen sense of self-preservation and like tothink about new things before they react, which is often misinterpreted asstubbornness.

But certainly they would have enough sense not to feed froma beehive!

- Online Sky Maps and More

- Sky Calendar & Moon Phases

- Astrophotography 101

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and otherpublications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.