Stars Become Two-Faced When They Explode

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

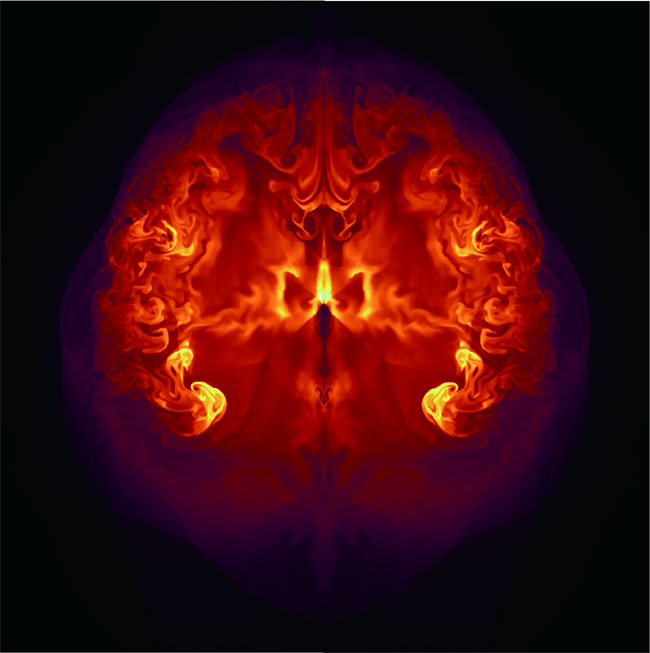

The death of a star in a supernova explosion can brieflyoutshine an entire galaxy in cosmic conflagrations that many astronomersthought exploded with some symmetry. But new observations suggest supernovascan be unbalanced, beginning on one side of the star to create oddballexplosions.

Depending on the angle that astronomers viewa supernova, it will look somewhat different, like two faces of the samecoin, researchers said.

The discovery helps solve a mystery about a certain type ofsupernova called Type 1a. These explosions are thought to be very uniform, andare prized by astronomers for that quality.

However, observers noticed two subcategories of these supernovasthat behave differently over time, with some spewing out material very quickly whileothers exploded with comparative leisure. Now it appears the two subcategoriesare actually the same thing, seen from different angles.

One supernova, two faces

According to the new study, whether a supernova appears tobe exploding rapidly or slowly just depends on which side is facing us.

"Now we show this diversity in appearance is simply aconsequence of this orientation," said lead researcher Keiichi Maeda ofthe University of Tokyo in Japan. "Now it means that these two categoriesare not really two populations."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers resolved the two-faced nature of these supernovasby observing a group of them years after their explosions peaked. At thispoint, the dying stars had expelled much of their material in a translucentcloud of debris that telescopes can peer through to see into the heart of theaging supernova.

By studying the distribution and relative speed of thedebris, the astronomers could deduce the original directionof the explosion.

The finding also helps astronomers understand the complicated mechanics at theheart of these stellar explosions. For one thing, models that depict supernovasas spherical explosions should be replaced with asymmetric depictions.

"This is kind of a paradigm change in the study of Type1a supernovae," Maeda told SPACE.com.

Maeda and his team detail their findings in the July 1 issueof the journal Nature.

Supernova candles

The finding has important ramifications for observers,because it reaffirms the usefulness of Type 1a supernovas as a cosmic distanceindicator, or so-called standard candle.

"The requirement for a good standard candle is thatthey look basically the same in every observed characteristic," Maedasaid.

All Type 1a supernovas shine at roughly the same peakbrightness - about 10^36 watts. That's because all they begin when a smallstar, called a white dwarf, sucks up mass from a companion star.

White dwarfs have a set limit to how massive they can becomebefore they explode, so when they do finally hit the limit, the explosionsalways blast out roughly the same amount of energy.

If one of these explosions appears brighter than another, itmust be because it is closer to us. So by measuring how bright a Type 1asupernova appears, and comparing that with its known actual, intrinsicbrightness, astronomers can calculate how far away it is.

So the idea that they might not actually be as uniform as wethought would put many distance calculations into question, including some ofthe fundamental calculations on the rate the universeis expanding that use Type 1a supernovas.

"Even a small systematic difference in their luminositywould potentially jeopardize the usefulness of Type 1a supernova as precisiondistance indicators," wrote astronomer Daniel Kasen of the University ofCalifornia, Berkeley, in an accompanying essay in the same issue of Nature.Kasen was not involved in the new research.

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- What is a Supernova?

- How Long Do Stars Live?

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.