Should Pluto Be a Planet After All? Experts Weigh In

Now that Pluto may have regained its statusas the largest object in the outer solar system, should astronomers considergiving it back another former title — that of full-fledged planet?

Pluto was demoted to a newly createdcategory, "dwarf planet," in 2006, partly because of the discovery ayear earlier of Eris, another icy body from Pluto's neighborhood. Eris wasthought to be bigger than Pluto until Nov. 6, when astronomers got a chance to recalculateEris' size.

The new finding brings renewed attention toPluto, and to the controversial decision to strip the frigid world of itsplanet status. Should Pluto be a planet? Should Eris, and many other objectscircling the sun beyond Neptune's orbit? Or is the current system, whichrecognizes just eight relatively large planets, the way to go? [POLL:Should Pluto's Planet Status Be Revisited?]

SPACE.com asked some experts to weigh in onthis debate, which affects how astronomers view the solar system, as well ashow complicated schoolchildren's planet-memorizing mnemonics must be:

The background: Pluto's demotion

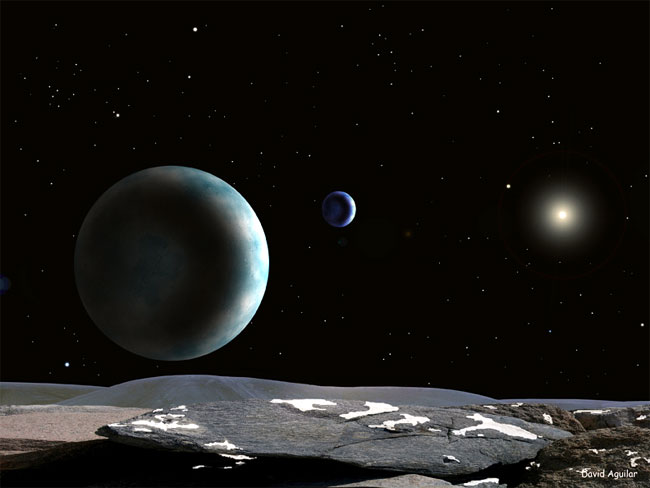

Eris is about 9 billion miles (15 billion kilometers)from the sun at its farthest orbital point, making it about twice as distant asPluto. Its discovery in 2005 ultimately led astronomers — uncomfortablewith the prospect of finding many more planets in the frigid outer reaches ofthe solar system — to reconsider Pluto's status.

In 2006, the International Astronomical Unioncame up with the following official definition of "planet:" A bodythat circles the sun without being some other object's satellite, is largeenough to be rounded by its own gravity (but not so big that it begins toundergo nuclear fusion, like a star) and has "cleared itsneighborhood" of most other orbiting bodies.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Since Pluto shares orbital space with lots ofother objects out in the Kuiper Belt — the ringof icy bodies beyond Neptune — it didn'tmake the cut.Instead, the IAU rebranded Pluto, and Eris, as "dwarf planets."

Dwarf planets are not officially full-fledgedplanets, so Pluto was stripped of the status it had held since its discovery in1930. Eight planets officially remain: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter,Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

The case against Pluto

The scientist who discovered Eris, Caltechastronomer Mike Brown, thinks Pluto's demotion was the right move. Pluto, Erisand the many other KuiperBelt objectsare far too different to be lumped in with the eight official planets, he said.[MikeBrown: Q & A With the Man Who Killed Pluto]

For one thing, they're much smaller. Pluto isabout 1,455 miles (2,342 km) wide. The smallest official planet, Mercury, ismore than twice as big at 3,032 miles (4,880 km) across.

The dwarfs' orbits tend to be very different,too — much more elliptical and more inclined, relative to the plane ofthe solar system. And they're made of different stuff, with ices comprisingmore of their mass.

"It just makes no sense from aclassification standpoint to take these objects that clearly belong togetherand pick one — or two, or a dozen — and say, 'Oh, these belong withthe very different, large, planet-like things," Brown said.

The only reason Pluto was ever deemed aplanet, Brown added, is because it was first detected so long ago, before peoplerealized that it was just one of a vast flotilla of objects beyond Neptune'sorbit.

The Kuiper Belt— which is now known to host more than 1,000 icy bodies, with many morelikely to be discovered — wasn't even discovered until 1992.

"It's just a funny historical accidentthat we found Pluto so early, and that it was the only thing known out therefor so long," Brown told SPACE.com. "No one intheir right mind would not have called it a planet back then, because we didn'tknow any better."

Astronomers have a much better sense of whatPluto is now, according to Brown.

"We have progressed so much further inour understanding of what the solar system is that it's pretty obvious,"he said. "We can go back and reassess the mistakes of our ancestors."

So Pluto should take its rightful placealongside other Kuiper Belt objects rather thanconsort with the "real" planets, some astronomers say.

"I group Pluto with the other icy bodiesin the Kuiper Belt," said Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of New York City's HaydenPlanetarium. "I think it's happier there, actually. Pluto has family inthe outer solar system."

Tyson was one of the first to push forPluto's demotion. A decade ago, when he and the Hayden staff redesigned theplanetarium's exhibits, they lumped Plutowith the Kuiper Belt objects rather thanwith the eight official planets.

The case for Pluto

Yet some astronomers still bristle at the reorganizationof the solar system, and not because Pluto's demotion spoiled the popular"My Very Energetic Mother Just Served Us Nine Pizzas"planet-memorizing aid.

Rather, the IAU's planet definition isfundamentally flawed, some astronomers say.

They take particular issue with the"clearing your neighborhood" requirement, for several reasons.

"If you take the IAU's definitionstrictly, no object in the solar system is a planet," said Alan Stern, aplanetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo."No object in the solar system has entirely cleared its zone."

The definition also sets different standardsfor planethood at different distances from the sun,according to Stern, who is principal investigator of NASA's New Horizonsmission, which is sending a spacecraft to Pluto.

The farther away a planet is from the sun, thebigger it needs to be in order to clear its zone. If Earth circled the sun inUranus' orbit, it wouldn't be able to clean out its neighborhood and would thusnot qualify as a planet, Stern said.

"It's literally laughable," he toldSPACE.com.

In Stern's view, a planet is anything thatmeets the IAU definition's first two criteria — the bits about orbitingthe sun and having enough mass to be roughly spherical, without the"clearing your neighborhood" requirement.

So Pluto should be a planet, as should Erisand the dwarfplanet Ceres(the largest body in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter), as well asmany other objects.

Such a definition would greatly expand thelist of planets in the solar system.

Many astronomers were uncomfortable with thisprospect, according to Stern, and that discomfort was a big factor in thedecision to demote Pluto. It stemmed from an unscientific desire to keep thenumbers low.

"Many people think it's special to be aplanet," Stern said.

But adding a bunch of names to the listwouldn't cheapen the ones that had been there forever, he added. It wouldsimply reflect astronomers' increasing understanding of the solar system. Inthat understanding, small, icy planets far outnumber big gassy or rocky ones.

"There are a large number of planets,and most of them are small," Stern said. "It's the Earth-like planetsand the giant planets that are freakish."

For what it's worth, Stern doesn't object tobranding Pluto a "dwarf planet" — he said he coined the term— as long as dwarfs are still considered planets.

What's in a name?

The battle over Pluto's planethoodmay be more semantic than anything else. But words do matter, because theyshape how people classify and understand reality.

"You have to be able to sort,"Stern said.

Tyson said he tries not to use the word"planet" in its traditional, generic sense too much, because itdoesn't convey very much meaningful information. It's more revealing to groupobjects that are similar in size, composition and other properties.

"The word 'planet' has far outlived itsusefulness," Tyson told SPACE.com. "It doesn't celebrate thescientific richness of the solar system."

So Tyson thinks in categories such as gasgiants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune) and terrestrial planets (Mercury,Venus, Earth and Mars) as well as asteroids and KuiperBelt objects (Pluto, Eris and many others).

For his part, Brown thinks stripping Pluto ofits planethood doesn't make the icy body any lessinteresting or important.

"I think that Pluto as an example of alarge Kuiper Belt object is so much more interestingthan Pluto as this very weird planet at the outer edge of the solar systemunlike anything else," Brown said. "We are going to learn so muchmore about the solar system with our new understanding of what Pluto is."

Maybe Stern and other scientists fighting forPluto's planethood would agree. Or maybe not.

- The Man Who Killed Pluto: Q & A with Astronomer Mike Brown

- POLL: Should Pluto's Planet Status Be Revisted?

- Top 10 Extreme Planet Facts

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.