Earth-Sized World Could Lurk in Outer Solar System

Some astronomers saythat a planet the size of Mars or Earth could be lurking on the fringes of oursolar system. But even the latest space telescopes that launched in 2009 standlittle chance of finding such a distant object.

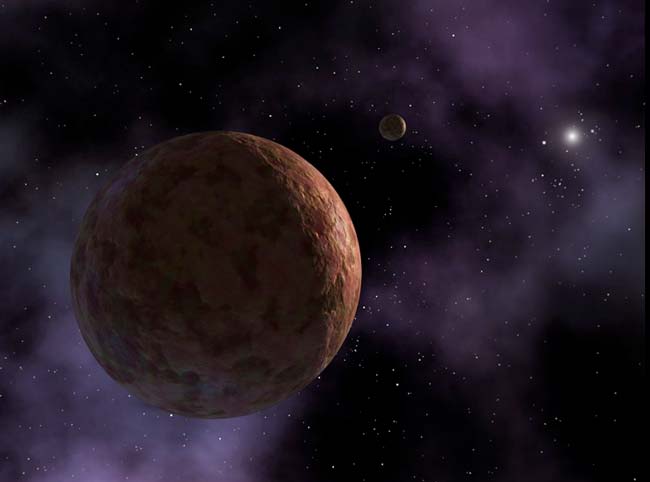

Such a world, if itexists, would probably have an orbit far beyond Pluto or similar dwarf planetsin the outer solar system. It would likely resemble a frozen versionof Mars or Earth at best, a most unsuitable home for life. And it would notbe alone.

"When the solarsystem's story is finally written, it's much more likely that it will havecloser to 900 planets rather than the nine that we grew up with," saidAlan Stern, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colo.

Just a handful of thosepotential discoveries might reach the size of Earth, compared to a swarm ofPluto-sized bodies that Stern and others expect to find.

Each object ? beit termed a planet, dwarf planet or otherwise ? would serve as a frozentime capsule that could reveal much about the early evolution of the solarsystem. It could even force scientists to once again rethink the definition ofa planet, following the controversial downgradingof Pluto to a dwarf planet.

Beyond the belt

Pluto's downfall camein part because astronomers discovered a number of smaller planetary objects inthe outer solar system. Dwarf planets such as Eris occupy a cluttered, icyregion beyond Neptune known as the Kuiper Belt. But a planet the size of Marsor Earth has not turned up at such range.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"For the KuiperBelt we can already say there is nothing Earth or Mars sized, as its dynamicaleffects would be easily seen," said Mike Brown, an astronomer at Caltechwho led teams that discovered Eris (and nicknamed it ?Xena? at first) and otherdwarf planets.

One of Brown's pastdwarf planet discoveries, Sedna,occupies a strange elliptical orbit between the Kuiper Belt and the moredistant Oort Cloud ? a possible sign of the gravitational influence of anotherworld as big as Earth, one astronomer proposed. But Brown suspects that such a largeobject would have been spotted already.

Brown and Stern saythat the Oort Cloud represents a more likely prospect for worlds the size ofMars or Earth. The Oort Cloud surrounds our solar system with billions of icybodies at distances as far out as 50,000 times the distance between the sun andEarth.

"Once you gobeyond the Kuiper Belt, to the Sedna region or the Oort Cloud, you can alwayshide things by putting them farther away," Brown told SPACE.com.

How they got there

Brown noted that anyfuture discovery of larger objects in the outer solar system would eithersuggest that scientists have the wrong idea of how planets form, or mightindicate that the early solar system had more material available thanpreviously suspected.

"More interestingto me, though, is that it would be an entirely new class of large body,"Brown said. "We don't have any ice rich planetary-sized bodies in thesolar system, so we don't really know what they would be like and how theywould work."

Stern has longsupported the idea of many planet-sized lurkers in the outer solar system. Hereferred to computer models that show how medium-sized planets might haveformed during the chaotic creation of gas giants such as Jupiter, when swirlingsmaller pieces clumped together to form larger bodies.

"Giant planets gravitationallycleared out regions between them, with each capable of throwing small andmedium size planets into the deep solar system," Stern explained.

Define 'planet' forme

Such small or mediumplanets hanging out in the distant reaches of the solar system would cast reneweddoubt on the 2006 ruling of the International Astronomical Union (IAU).Stern has heavily criticized the IAU's decision, which demoted Pluto in partbecause of its location in the solar system.

"The IAU isslowly beginning to realize that it has made a great mistake," Stern said.He predicted that the organization would retract its 2006 decision if newplanet-sized discoveries emerge in the future.

Brown stood by the IAUdecision as a "very clear definition" that has scientific usefulness.But he too acknowledged the likely complications with outer solar systemplanets the size of Mars or Earth.

"It seems prettyobvious that if something Earth sized is discovered, everyone is going to callit a planet," Brown said. "So then we are back to the drawing board,unfortunately."

A question of when

The prospect of biggerplanets farther out may have to wait until scientific detection improves. Sterncompared the search with existing space telescopes to "looking at the skythrough a soda straw," because most telescopes have extremely narrow viewsof the sky. Even the most powerful telescopes can only directly spot planetaryobjects about 10 times farther out than Pluto.

NASA's new WISEspacecraft has a very slim chance of spotting a close-in planet with itsall-sky infrared survey, Brown and Stern agreed. But they both have higherhopes for the upcoming Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, which should have theability to spot Earth-sized objects as far out as perhaps 1,000 astronomicalunits (AU), where 1 AU is the Earth-sun distance.

That 1,000 AU stillfalls short of the Oort Cloud's vastness, which occupies a region tens ofthousands of AU away. Still, Stern suggested that future space explorationmight even reach distant Earth siblings ? a can-do attitude that perhapsreflects his role as principal investigator for NASA's outbound New Horizonsprobe headed for Pluto.

"The Oort Cloudis the solar system's attic, with all sorts of stuff up there," Sternsaid. "We just don't have a big enough ladder to go up and look aroundyet."

- Moon's Like Avatar's Pandora Could Be Found

- Object Larger Than Pluto Called 10th Planet

- Gallery: Our New Solar System

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.