Pluto's Identity Crisis Hits Classrooms and Bookstores

NEW YORK ? Pluto was once a planet.Then, a dwarf planet. And as of last week, a plutoid. The fall from grace hasteachers, parents and educational publishers struggling to keep up, while kidsremain loyal to their favorite, the ninth planet. Underscore planet.

Last week,the International Astronomical Union (IAU) announced Pluto should now be calleda "plutoid," two years after the organization votedto demote Pluto to "dwarf planet" status.

Meanwhile,many kids are nearly certain Pluto is still a planet.

"Ithink it's a planet. But me and my friends, we talk about it sometimes and wego back and forth," said Natalie Browning, 9, sitting in a park in Manhattan with her family. "Right now, I'm not 100 percent. I'm just 75 percent"sure that Pluto is a planet.

Natalie'smom, Bobbie Browning, said, "You've got kids with textbooks saying thatPluto is part of the solar system and a planet, and teachers have to say itisn't [a planet]."

Science teachersand publishers already worked to update their resources to read "dwarfplanet." And now, boom, that category is out of favor among astronomers.

"Studentswho have just learned about the concept of dwarf planets must now be taught thenew concept of plutoid," said Janis Milman, who teaches earth science at Thomas Stone High School in Maryland. "This will lead to confusion in the classroom andresistance to learning the new terms, because the students will question, whylearn something that might change again in a year or so?"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A cursorysurvey at a large chain bookstore here revealed three out of four books publishedin 2006 or later were updated, with Pluto designated as a dwarf planet and thesolar system said to include just eight planets.

Chroniclesof Pluto

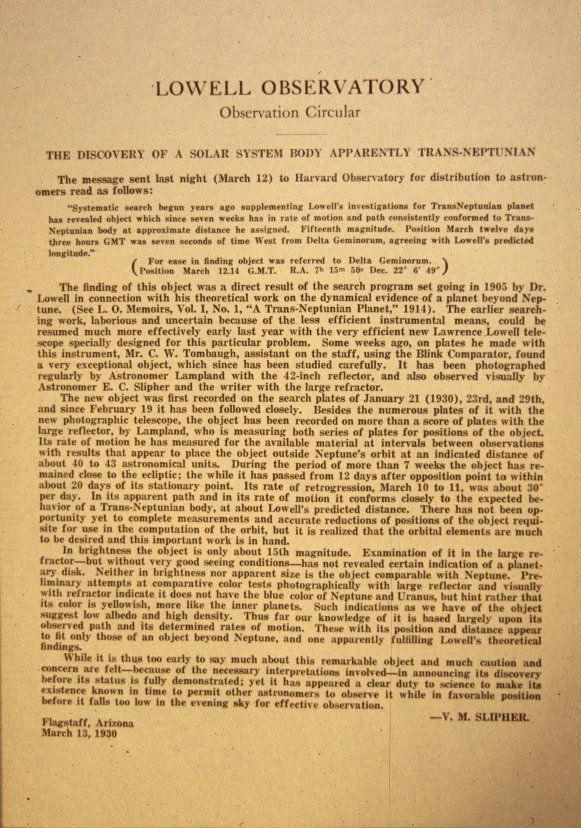

Discoveredin 1930 by Clyde W. Tombaugh at Lowell Observatory in Arizona, Pluto was alwaysconsidered an oddball of sorts, with its tiny size (smaller than some moons)and eccentric orbit.? During its 248-year trek around the sun, Pluto swingsfrom its farthest point from the sun at 49.5 astronomical units (AU) to asclose as 29 AU from the sun. One AU is the average distance between the Earthand sun, or about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

More than70 years later, in August 2006, 424 astronomers at an IAU meeting voted todemote Pluto to dwarf planet status. Last week, the IAU Executive Committee reclassifiedPluto as a plutoid. The other object in the plutoid club, Eris, is largerand more massive than Pluto.

Astronomersexpect to find hundreds of Pluto-sized objects. And so the fate of Pluto willdetermine how these worlds are classified. For instance, new computer modeling suggests anobject up to 70 percent of Earth's mass is lurkingbeyond Pluto. This "Planet X," if confirmed, would be called aplutoid under the IAU's scheme.

No matter what the scientists say, many kids won't let go.

"It'sa planet," said fifth-grader Emily Mitchell, whose mother Laurie agreed,saying, "I grew up learning it was a planet."

"It'sthe smallest planet," said Liam, a 4-year-old who is "about to be5." Liam's teacher Rachel Kaplan said, "I was really sad when Plutowas declassified as a planet, because I've studied astrology for a number ofyears."

AileenWilson said her 7-year-old son is interested in Pluto's label. "He'sinterested in why it was a planet and why it's not a planet anymore."

"Iknow that it was demoted and it's not a planet. But I don't know what it'scalled," said Erin Kelly, a pre-school teacher sitting on a park benchwith her students in New York.

In theclassroom

Even as scientistsare arguing over the "plutoid" designation, with some saying theywon't use the term, educators are already latching onto it.

Change is the name of the game in science, according to Gerry Wheeler, theexecutive director of the National Science Teachers Association.

"Basically,it's a teachable moment for science teachers, because it shows the dynamicnature of science," Wheeler told SPACE.com. He added the NSTA willspread news of the plutoid category to science teachers in the fall.

Elementaryschool science teacher Lucy Jensen agrees: "Pluto has made it interestingstudying our planets this year." She teaches at Joliet Public School in Montana. "Our only problem we now have is buying new material, such as posters,videos, DVDs and game/study materials that need to be updated," she said.

Jensenadded that while her fourth-grade students were more upset than the thirdgraders about Pluto's demotion, the parents were the most upset. "It ishard to teach old dogs new tricks, and we like what we know," she said.

"Timehas always been taken in the classroom to ponder the origin of Pluto. WhenPluto became a dwarf planet, along with Eris and Ceres, it made it easier toexplain why an object of Pluto's small stature could be classified,"high-school teacher Milman said. "Now we will just need to teach them morenew definitions."

Milmanadded that "dwarf planets" is an easier term for students to graspcompared with plutoids. "Objects of Pluto, Eris and Ceres' size are toosmall to be called planets so they were called dwarf planets. That was easierfor the students to understand," she said.

Yet manystudents are still unaware of the change made in 2006.

"Myfourth graders still consider Pluto a planet," said Bev Grueber, a scienceteacher at North Bend Elementary in Nebraska. "We do extensive oralreports on the planets to meet a state standard, and everyone jumps for joywhen they get Pluto. Last year, I left Pluto out of the draw and they askedwhere it was, so they still consider it a planet regardless of what the spacescientists tell us the definition of that planet is."

AramFriedman, who founded Ansible Technologies Ltd. in New Jersey, travels toschools to teach about astronomy using a portable planetarium. In a typicalfifth-grade class, he teaches students the features of the inner planets andthe outer planets. Pluto, he says, doesn't fit into those categories. Thatmakes sense to kids.

Publishinglag

Manyscience textbooks have only recently caught up with the dwarf planet concept.

Forpublisher McGraw Hill Education, the 2008 elementary and secondary schoolscience textbooks describe Pluto as a dwarf planet.

Middleschools with the current Holt Science and Technology textbooks would see Plutodefined as a dwarf planet. McDougal Littell Science took a slightly differentapproach.

"Wedidn't say how many planets there were, so we didn't have to make a lot ofchanges. We explained, historically, that it had been classified as a planetwhen it was discovered," said Dan Rogers, vice president and director ofHolt McDougal's science and health product development.

McDougal'steacher's edition included a detailedexplanation of Pluto's dwarf planet status.

"Oneof the reasons we were cautious is because we thought the whole thing wasunresolved and was going to change again," Rogers said. "We're in theprocess of developing a brand new program, a new set of books."

In"Traveler's Guide to the Solar System," an astronomy book publishedin 2007 for kids age 8 to 10, the author notes, "Earth is the third ofnine planets (some say eight, some say ten, but nine is kind of traditional),orbiting our local star, the Sun."

Starry Night,astronomy software that includes educational resources, refers to Pluto as adwarf planet, according to content director Pedro Braganca. (Starry Night is adivision of Imaginova Corp., which also owns SPACE.com.)

And soon, educational publishers may need to re-update material. Wordhas it astronomers are vowing topursue a reinstatement of Pluto as a planet.

- Why Planets Will Never Be Defined

- The History of the Pluto Controversy

- Gallery: Our New Solar System