Dwarf Planet Eris May Be Smaller Than Pluto After All

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Thisstory was updated at 7:45 p.m. ET, Nov. 9.

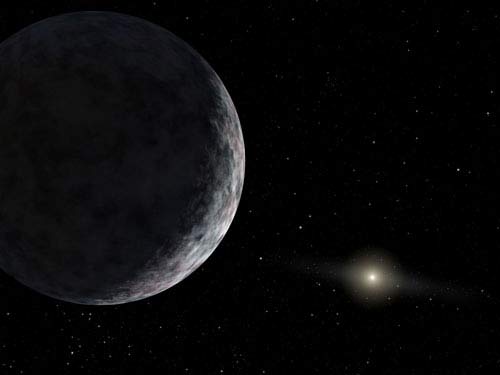

The dwarf planet Eris —once thought to be the largest body in the solar system beyond Neptune's orbit— may actually be smaller than Pluto, new observations suggest.

Three teams of astronomerswatched through telescopes as the icyEris passed in front of a distant star over the weekend. Thelength of the occultation — as the event is called — showed thatEris is likely less than 1,454 miles (2,340 kilometers) wide, the magazine Sky &Telescope reported.

This would make Eris a smidgesmaller than Pluto, which is about 1,455 miles (2,342 km) wide.

Astronomers still believe Eris tobe about 25 percent more massive than Pluto. So if Pluto is a bit bigger, orroughly the same size, Eris must be much denser. It must be made of differentstuff, which comes as a big surprise to some astronomers.

"The fact that theirdensities are so different is totally unexpected," said Mike Brown ofCaltech, who discovered Eris in 2005. Brown was not involved in the occultationmeasurements. "Eris is no longer a Pluto twin. It's an entirely differentobject." [POLL: Do You Think Pluto's Planet Status Should Be Revisted?]

The size revision would allowPluto to regain its status as the largest body in the KuiperBelt, the icy ring of objects circling the sun beyond Neptune. Pluto couldtherefore exact a small measure of revenge, foritwas demoted from ninth planet to dwarf planet in 2006 partly dueto the discovery of Eris (and later Eris' moon Dysnomia).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new observation efforts,which involved dozens of astronomers around the world, were coordinated byBruno Sicardy of the Paris Observatory.

Dueling dwarf planets

Eris has one known moon and ahighly elliptical orbit, zooming about 9 billion miles (14.6 billion km) fromthe sun at its farthest point — making it about twice as distant asPluto.

Early measurements of its size byBrown and others at the time suggested that Eris was slightly larger thanPluto.

Observations by both the Hubbleand Spitzer space telescopes, for example, pegged Eris' width as roughly 1,491miles (2,400 km). A research team using a Spanish radio telescope calculatedEris to be even bigger, around 1,864 miles (3,000 km) across.

The discovery of a "10thplanet" larger than Pluto — and the prospect of finding an 11thplanet, and a 12th and so on — ultimately led astronomers to reconsiderPluto's status as a full-fledged planet.

In 2006, the InternationalAstronomical Union officially designated Eris and Pluto "dwarfplanets," based on the fact that they hadn't cleared their orbital zonesof other rocky objects.

The decision introduced a newcategory of body, and it officially reduced the number of planetsin the solar system to eight. It also set off a controversy that still simmers today; someastronomers agree with the move, while others regard Pluto as a full-fledgedplanet.

Resizing Eris

The new observations could helptake a bit of the sting out of Pluto's demotion.

In an international effort led bySicardy, dozens of astronomers around the world aimedtheir telescopes at Eris on Saturday (Nov. 6). Because the dwarf planet is sosmall and so far away, witnessing the occultation was no sure thing. It wouldonly be visible from certain spots on Earth's surface.

But three teams of astronomers,using different telescopes set up throughout the Chilean Andes, had success.They watched Eris pass in front of a faraway star in the constellation Cetus and timed how long Eris blocked the star's light.

Such information, if recorded atmultiple sites, can reveal with great precision how wide a spherical object is.(Astronomers think both Eris and Pluto are spherical). The size calculationsmade over the weekend may be more reliable than the earlier figures, accordingto Brown.

"Most of the ways we have ofmeasuring the sizes of objects in the outer solar system are fraught withdifficulties," Brown wrote on his blog Sunday (Nov. 7). "But,precisely timed occultations like these have thepotential to provide incredibly precise answers."

Rethinking the outer solarsystem

If the new measurements areaccurate, they make a strong case that Eris and Pluto are very differentobjects.

While the two dwarf planetsappear to have very similar surfaces, their interiors are likely quitedisparate. Since Eris is apparently much denser, it probably contains more rockand less ice than Pluto, Brown said.

Why are these two far-flungbodies made of different stuff? One possibility, according to Brown, is thatEris formed much closer to the sun than Pluto did, perhaps in the asteroidbelt, then was flung to the solar system's outer reaches later.

Brown regards this as unlikely,though, because Eriscontains more mass than the entire asteroid belt put together.

"I don't think this is theanswer, but it needs to be thought about," he told SPACE.com.

Another possibility is that Erisand Pluto have had very different histories, with Eris being hammered by morecosmic collisions. There's no obvious reason why this should be the case, Brownsaid, but it needs to be considered.

However Pluto and Eris came to beso different, astronomers have a lot of new information to mull over.

"My view of the outer solarsystem right now is different than it was a week ago," Brown said.

- POLL: Do You Think Pluto's Planet Status Should Be Revisted?

- Top 10 Extreme Planet Facts

- Gallery: The New Solar System

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.