Cosmic Heat Wave Caused Patchy Galaxy Formation

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

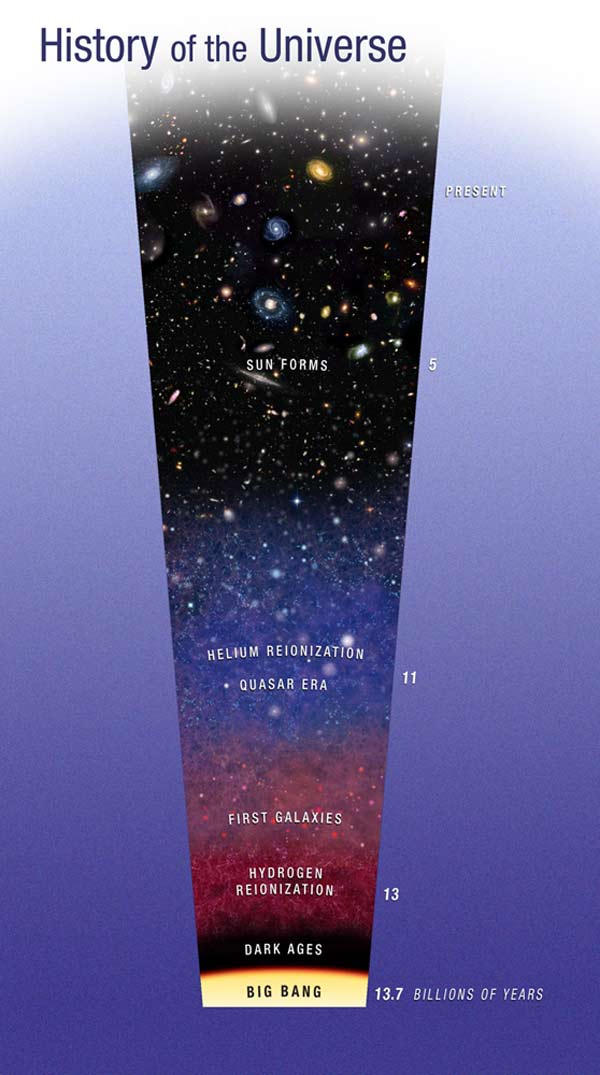

A galacticheat wave 11 billion years ago unleashed fierce blasts of radiation thataltered how some galaxies formed, a new study finds.

During thisperiod of universal warming ? which astronomers identified as 11.7 to 11.3billion years ago ? ultraviolet light, emitted from quasars, stripped electrons from heliumatoms in a process known as ionization. The resulting heat wave stunted thegrowth of some dwarf galaxies for nearly 500 million years, researchers said.

Quasars arefound in the centers of some faraway galaxies and contain supermassive black holes. These extremely luminous cosmicobjects ? bright in radio waves, X-rays and other forms of electromagneticradiation ? can be detected from more than 10 billion light-years away. Aquasar's energy is thought to emerge from matter spiraling at high speeds intothe supermassive black hole.

In the new study,the researchers used the Hubble Space Telescope to determine that a burst of quasaractivity caused heating of the intergalactic helium from 18,000 degreesFahrenheit (over 9,980 degrees Celsius) to nearly 40,000 degrees F (over 22,200degrees C). This hot spell inhibited the intergalactic gas from gravitationallycollapsing to form new generations of stars, affecting the formation of smallgalaxies. ?[HubbleTelescope's Most Amazing Discoveries]

"In theearly universe, this burst of heating, we think, prevented a lot of theselow-mass galaxies from forming stars," study leader Michael Shull, aprofessor of Astrophysics and Planetary Sciences at the University of Coloradoin Boulder, told SPACE.com. "This burst of heating goes into theintergalactic helium, heats the gas up, and changes galaxy formation,particularly with dwarf galaxies."

The researchwill be detailed in the Oct. 20 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.?

Lookingthrough Hubble's eyes

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Shull andhis team of researchers used Hubble's Cosmic Origins Spectrograph to probe theinvisible, remote universe with improved power and sensitivity, compared toother space-based spectrographs.

Theastronomers studied the spectrum of ultraviolet light produced by a quasarlocated approximately 11 billion light-years away.

"I wouldn'tcall it the edge of the universe, but it's getting close," Shull said.

The observationsallowed the researchers to produce more detailed measurements of theintergalactic helium than had previously been possible.

"Forthe first time, we saw that the heating is intermittent from one place toanother," Shull said. "Quasars are very far apart ? millions oflight-years apart ? so that creates very patchy re-ionization. You have patchesthat are cold and dark, and other patches that are ionized and heated."

"Dwarfgalaxies in the dark zone didn't get stunted," he said. "In thepatches that are ionized and heated, these galaxies get stunted in their growthor are maybe even destroyed."

Pinningdown a time

For the lastfive years, theorists have been trying to pin down the consequences of"helium re-ionization" in the universe, Shull said.

The processis known as helium re-ionization because the universe went through an initialheat wave more than 13 billion years ago, when energy from early massive starsionized cold interstellar hydrogen from the Big Bang that started the universe.The universe is estimated to be about 13.7 billion years old.

As a resultof the theoretical work, scientists knew what to expect, but until now, did notknow the exact timeframe of when this re-ionization took place.

"Now weknow when it happened," Shull said. "I imagine quite a few more dwarfgalaxies may have formed if helium re-ionization had not taken place."

The helium'sre-ionization occurred at a transitional time in the universe's history, when galaxies collided to ignite the energetic quasars.

There-ionization of the helium, and the concurrent warming effect, was spread outover the course of over 500 million years, after which the intergalactic gascooled down and dwarf galaxies were able to resume their normal process offormation.

Shull andhis research team are already hard at work following up on the results of thisstudy. Since their initial observations only had one perspective with which tomeasure helium's transition to its ionized state, the researchers are keen onexpanding these measurements using sightlines around the quasar, as well asdifferent quasars in other parts of the universe.

"We'regoing to look at a couple more quasars in a different neck of the woods to seeif this is happening the same way everywhere," he said.

- MostAmazing Hubble Telescope Discoveries

- Gallery- 20 Years of the Hubble Space Telescope

- Doesthe Universe Have an Edge?

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.