Some of the Universe's First Galaxies Discovered

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

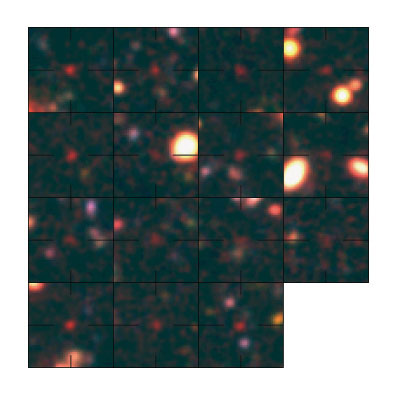

A new survey has found 22 of the earliest galaxies to formin the universe, confirming the age of one at just 787 million years after the theoreticalBig Bang.

These and other galaxies from the universe?s childhood couldhelp shed light on the conditions that governed the early universe.

With recent technological advances, astronomers have beenable to observe more of the so-called reionizationera, the farthest back in time that astronomers can observe.

Universe's first light

For the first few hundred thousand years after the BigBang (which took place about 13.7 billion years ago), the universe was ahot, murky mess, with no light radiating out. Because there is no residuallight from that early epoch, scientists can't observe any traces of it.

But about 400,000 years after the Big Bang, temperatures inthe universe cooled, electrons and protons joined to form neutral hydrogen(meaning it had no charge), and the murk cleared. Some time before 1 billionyears after the Big Bang, neutral hydrogen began to form stars in the firstgalaxies, which radiated energy and changed the hydrogen back to being ionized,or charged. This was what astronomers call the reionization period.

But while astronomers know that this period was over byabout the time the universe was 1 billion years old, they don't know exactlywhen it began ? when the firststars and galaxies began to illuminate the universe. They also don't knowwhether reionization started gradually or instantly.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To help answer this question a team of astronomers led by MasamiOuchi of the Carnegie Observatories used a technique for finding some of theearly, extremely distant galaxies.

"We look for 'dropout' galaxies," Ouchi said."We use progressively redder filters that reveal increasing wavelengths oflight and watch which galaxies disappear from or ?dropout? of images made usingthose filters."

Dropout galaxies

The specific wavelengths of light at which the 'dropout'galaxies appear can tell astronomer's their distance and age.

Ouchi and his colleagues studied an area over 100 timeslarger than any previous such study and so had a larger sample of galaxies.

"Plus, we were able to confirm one galaxy?s age,? Ouchisaid. ?Since all the galaxies were found using the same dropout technique, theyare likely to be the same age.?

The team's observations were made from 2006 to 2009 with thewide-field camera of the 8.3-meter Subaru Telescope in Hawaii.

Ouchi and his team compared their observations with thosefrom other studies looked at the rates of star formation, which can be gleanedfrom data on the density and brightness of galaxies, and found that they weredramatically lower from 800 millions years to about one billion years after theBig Bang, than thereafter.

Accordingly, they calculated that the rate of ionizationwould be very slow during this early time, because of this low star-formationrate.

"We were really surprised that the rate of ionizationseems so low, which would constitute a contradiction with the claim of NASA?sWMAP satellite. It concluded that reionization started no later than 600million years after the Big Bang," Ouchi said.

"We think this riddle might be explained by moreefficient ionizing photon production rates in early galaxies," he added. "Theformation of massive stars may have been much more vigorous than in today?sgalaxies. Fewer, massive stars produce more ionizing photons than many smallerstars."

Ouchi's findings will be detailed in a December issue of theAstrophysical Journal.

- Vote: Most Amazing Galactic Images

- Violent Explosion Is Most Distant Object Ever Seen

- How Did the Universe Begin?

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.