Violent Explosion Is Most Distant Object Ever Seen

Light from a star that exploded 13 billion years ago hasbeen detected, becoming the most distant object in the universe ever observed.

The light from the distant explosion, called a gamma-rayburst, first reached Earth on April 23 and was detected by NASA'sSwift satellite. Gamma-ray bursts are thought to be associated with theformation of star-sized black holes as massive stars collapse.

Within hours, telescopes around the world were turned on theburst ? the mostviolent explosions in the universe ? observing its fading afterglow toglean clues about its source and location.

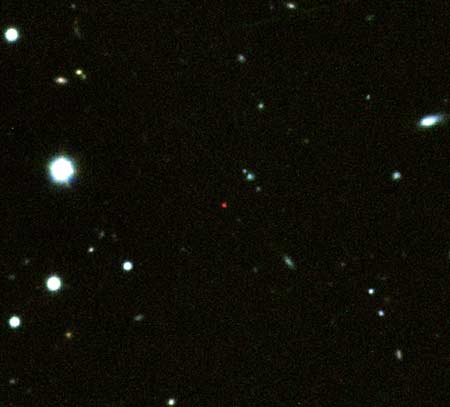

Two teams, one using the European Southern Observatory's8.2-meter Very Large Telescope, located in La Silla, Chile, and the other usingthe 3.6-meter Italian Telescopio Nazionale Galileo in Spain, pinpointed the distance to the blast, dubbed GRB 090423, at more than 13 billionlight-years from Earth. (The previousrecord holder, GRB 080913, was 12.8 billion light-years distant.)

This enormous distance means that the gamma-ray burstoccurred just 630 million years after the theoretical Big Bang, when theuniverse was only four percent of its current age.

'Spine-tingling' discovery

In recent years, astronomers have been detecting gamma-raybursts, galaxies and quasars at ever farther distances, closer to the birth ofthe universe's first stars and galaxies. So it was only a matter of time beforethey detected such an early explosion, said Nial Tanvir of the University of Leicester in the U.K. Tanvir worked on the ESO team.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We have been looking for a burst like this for severalyears, so we of course expected that we'd get lucky one day ? but it was a"spine-tingling" moment to realize that this was finally it," Tanvirtold SPACE.com.

Astronomers hope that observations of this and othergamma-ray bursts just as far away (and thought to represent some of the earlieststellar populations) will shed light on the so-called "cosmic darkages," a time before the first stars and galaxies ignited.

"This explosion provides an unprecedented look at anera when the universe was very young and also was undergoing drasticchanges," said Dale Frail of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory."The primal cosmic darkness was being pierced by the light of the firststars and the first galaxies were beginning to form. The star that exploded inthis event was a member of one of these earliest generations of stars."

Cosmic dark ages

After the BigBang, the universe had cool rapidly as it expanded. About 400,000 yearslater, free electrons and protons (negative and positive charges, respectively)combined to form neutral atoms, leaving the universe awash in a backgroundradiation that we currently can detect in the microwave part of theelectromagnetic spectrum (the so-called Cosmic Microwave Background).

The universe stayed in this neutral stage until the firststars and galaxies light it up. The photons from these stars knocked electronsfree from the atoms, "re-ionizing" the universe. But detecting themost distant galaxies and quasars from this period is difficult, and soastronomers are hoping that distant gamma-ray bursts such as GRB 090423 willgive them information about this re-ionization period.

It will likely take many more gamma-ray bursts to sayanything definitive about this cosmic dark age though.

At present, we have only a few observations from these earlyepochs. Thus, even a single, new data may provide useful constrain to ourmodels of the early Universe. However, to be frank, a decisive step forward forour knowledge of this period of the Universe's history requires the collectionof a relatively large sample of distant [gamma-ray bursts]," RubenSalvaterra of the National Institute of Astrophysics in Italy told SPACE.com. Salvaterra worked on the Italian Telescopio Nazionale Galileo team.

Both team's observations are detailed in the Oct. 29 issueof the journal Nature.

Asked how long he thought this distance record would hold,Tanvir replied, "Based on past experience, it could certainly be a fewyears before it's broken, but it wouldn't entirely surprise me if it wastomorrow." He said he did expect the next record holder to be anothergamma-ray burst.

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Vote: The Strangest Things in Space

- How Did the Universe Begin?

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.