How the First Stars Were Born

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

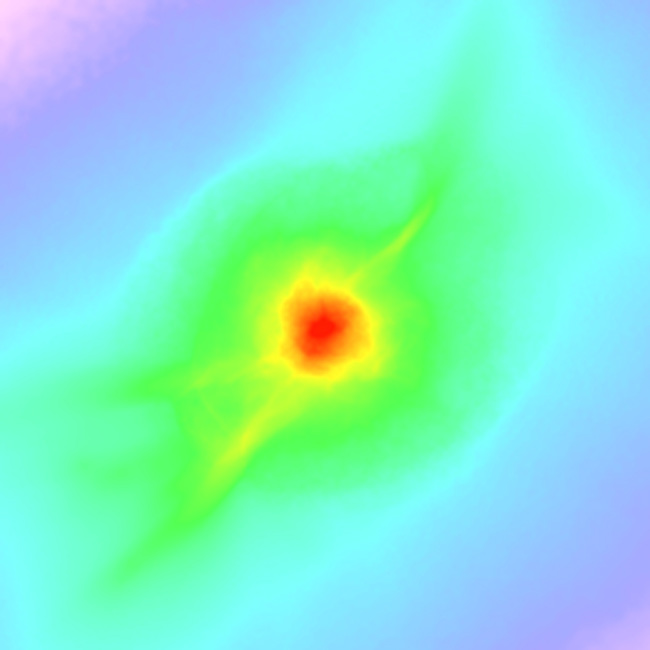

Anew supercomputer simulation offers the most detailed view yet of how the firststars evolved after the Big Bang.

Themodel follows the simpler physics that ruled the early universe to see how coldclumps of gas eventually grew into giant star embryos.

"Untilyou put that physics in the code, you can't evaluate how the first protostarsformed," said Lars Hernquist, an astrophysicist at Harvard University whose early-stars model is detailed in this week's issue of the journal Science.His remarks were made Wednesday during a press teleconference.

Mysterious "darkmatter" provided the first gravitational impetus for hydrogen andhelium gas to start clumping together, Hernquist said. The gas began releasingenergy as it condensed, forming molecules from atoms, which further cooled theclump and allowed for even greater condensing.

Unlikeprevious models, the latest simulation takes this cooling process of "complexradiative transfer" into account, said Nagoya University astrophysicist NaokiYoshida, who headed up the modeling project.

Eventuallygravity could not condense the gas cloud any further, because the densely-packedgas exerted a pressure against further collapse. That equilibrium point markedthe beginning of an embryonic star, called a protostar by astronomers.

Simulationruns show that the first protostar likely started with just 1 percent the massof our sun, but would have swelled to more than 100 solar masses in 10,000years.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Nosimulation has ever gotten to the point of identifying this important stage inthe birthof a star," Hernquist noted.

Thefirst protostars reached such massive size because they consisted of mainlysimple elements such as hydrogen and helium. That bloated existence means the starswhich eventually form from such protostars could create heavierelements such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen and iron in their fiery furnaces.

Theresearchers eventually hope to run the simulation all the way up through thepoint where protostars igniteinto true stars.

- Video: X-Ray-Emitting Black Holes

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- The Strangest Things in Space

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.