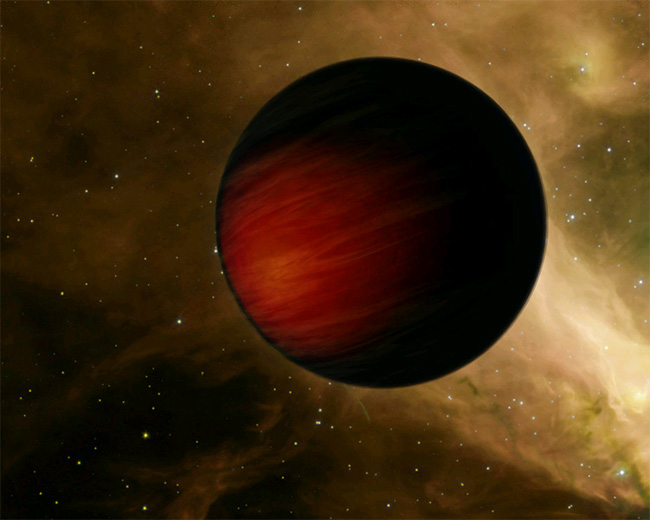

The hottest planet ever discovered is charcoal black and makes even some stars seem cool. Scientists think the exoplanet absorbs nearly all the starlight that reaches its surface and then reradiates it back out into space as heat.

Called HD 149026b, the feverish world emits so much infrared heat that it glows slightly. "It would look like an ember in space, absorbing all incoming light but glowing a dull red," said study leader Joseph Harrington of the University of Central Florida.

Located 279 light-years away in the constellation Hercules, HD 149026b is a so-called hot Jupiter, a giant gas planet that orbits very close to its star. It is a scorching 3,700 degrees Fahrenheit (2,040 degrees Celsius), three times hotter than Mercury and hotter than the coolest stars.

The finding is published online in the journal Nature.

An oddball world

Until very recently, HD 149026b was also the densest planet known. It contains higher levels of heavy elements-those other than hydrogen and helium-than all of the planets in our solar system combined, and its core might have up to 90 times the mass of the Earth.

"HD 149026b is simply the most exotic, bizarre planet," Harrington said. "It's pretty small, really dense, and now we find that it's extremely hot."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

HD 149026b is a so-called "transiting" planet, meaning its orbit takes it directly in front of its star as seen from Earth. Using NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, Harrington and his team measured the total light emitted by the planet-star system and used the information to calculate HD 149026b's temperature.

"We did those observations in 2005, and it's taken us two years to make sure that we believe them, which we do," Harrington told SPACE.com.

How did it get so hot?

How HD 149026b got to be so hot is a mystery. "We've actually done a lot of work to try and answer that question, but the more we think about it, the worse it gets," Harrington said.

One idea, proposed by Jonathan Fortney at NASA Ames Research Center in California, is that the planet is so hot that metals such as titanium and vanadium can exist in their gaseous forms in the planet's atmosphere.

Such metals are "very, very, very strong visible [light] absorbers," said Fortney, who was not involved in the new study.

Fortney also pointed out HD 149026b orbits a very metal-rich star, which could explain why the planet is so abundant in heavy elements. The planet's "atmosphere is probably enhanced in metals compared to most other planets, so it's probably more efficient at absorbing stellar light than other hot Jupiter planets," Fortney said.

Fortney thinks HD 149026b could be the first of a new subgroup of hot Jupiters. "I think what we'll eventually find is that hot Jupiters may end up falling into two classes," he said.

One class, Fortney said, would consist of relatively "cool" hot planets, in the range of about 1,300 to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (700 to 1,000 degrees C), and the other would have planets with temperatures of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,700 degrees C) or higher.

- Video: Planet Hunter

- Video: New Black Planet is Hottest Ever

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.