Asteroid Jiggles Like a Jar of Mixed Nuts

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

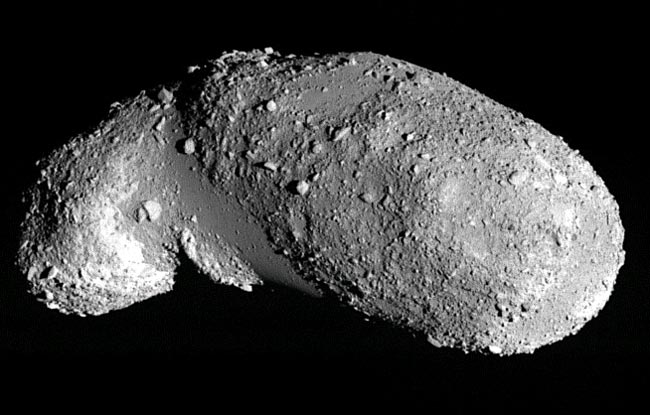

Like a jiggled jar of mixed nuts, shaking on the near-Earth asteroid Itokawa is sorting loose rock particles on its surface by size, causing the smallest grains to sink into depressions, a new study suggests.

Researchers analyzed images of a mix of boulders and gravel, called regolith, covering the surface of Itokawa. The images, taken by the Japanese Hayabusa spacecraft in 2005, revealed that some areas were coated with fine particles and appeared smooth, while others regions looked bumpy, as if the asteroid suffered an intense case of acne.

In a study detailed in the April 20 issue of ScienceExpress, an online publication of the journal Science, researchers suggest the regolith's patchy distribution is the result of shaking, which causes the finest and lightest materials to accumulate in dips on the asteroid's surface, where the local gravity is lowest.

"It's sort of like if you poured water over Itokawa, all the water would tend to pool in these [low] regions," said study team member Daniel Scheeres of the University of Michigan. "The water would flow downhill until it couldn't go downhill anymore."

A shaky asteroid

The new findings suggest seismic activity of some kind is occurring on Itokawa, a small asteroid only 1,600 feet (500 meters) in diameter.

"Even though it's this tiny little guy, it is in some sense geologically active," Scheeres told SPACE.com. "Things are happening on the surface. Stuff moves from one point to the other."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The regolith distribution suggests Itokawa has been shaken up in the past, but what might have rattled it is still an open question.

One hypothesis is that smaller asteroids occasionally strike Itokawa and shake the space rock up. Because of its diminutive size, even tiny impacts could send Itokawa into a tremor. Another idea is that Itokawa might occasionally fly close enough to the Earth, where our planet's gravity could jostle it.

Jostled by sunlight

Perhaps the most intriguing hypothesis, however, is one recently put forth by Scheeres. In a study to be published in the scientific journal Icarus, Scheeres ties Itokawa's periodic shaking to the YORP effect, in which sunlight provides a small nudge that can speed up or slow down an asteroid's rotation.

Computer simulations suggest radiation from the Sun is having the latter effect on Itokawa, causing it to spin slower and slower. Working backward, Scheeres reasons Itokawa must have spun faster in the distant past.

Wind the clock back 200,000 years, Itokawa might have spun around so fast that its head and body parts became separated and orbited around each other.

"We don't know that it actually breaks apart in this way, but given the fact that both of these [segments] are made up of boulders lying on top of each other, the head and body probably are in some sense disjoined," Scheeres said.

Occasionally, the two orbiting segments might have smacked back together again, like beating cymbals, and the vibrations might have jostled loose particles on Itokawa's surface around.

"You're talking impacts on the order of centimeters per second or less," Scheeres said.

Impact scattering

The new findings are also shedding light on how impact debris gets scattered on celestial bodies.

On larger bodies, like the Moon, most of the material ejected during an impact does not travel far and deposits around the crater. It was thus thought that on smaller objects with much less gravity, such as asteroids, ejecta is flung over a proportionally larger area, potentially coating the entire body.

"However, what we observed [on Itokawa] indicates that the evolution of regolith on asteroids might be more complicated than that, especially for small bodies," said study leader Hideaki Miyamoto, a researcher at the University of Tokyo and the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona.

"On Itokawa, there might be some processes that we are not aware of on other larger bodies," Miyamoto said.

- 2007 Guide: Find Bright Asteroids This Year

- VIDEO: Killer Asteroids and Comets

- IMAGES: Asteroid Gallery

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.