Moon Over Mars: Why US Needs a Lunar Mission First (Op-Ed)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

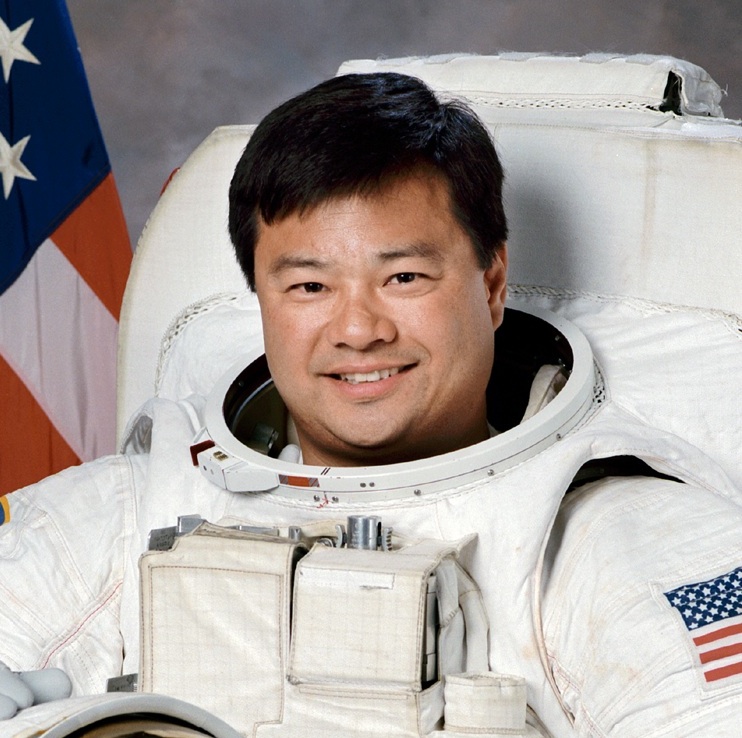

Leroy Chiao is a former NASA astronaut and ISS commander. He served as a member of the 2009 Review of U.S. Human Spaceflight Plans Committee, and is the special adviser for human spaceflight to the Space Foundation. Elliot Pulham is the CEO of the Space Foundation. A 30-year veteran space leader, he served as spokesman at the Kennedy Space Center for the Magellan, Galileo and Ulysses interplanetary missions, as well as for numerous space shuttle and U.S. Department of Defense missions. He holds the U.S. Air Force Distinguished Public Service Medal, the service's highest civilian honor. The authors contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Wanting to send astronauts to Mars seems all the rage these days, and the popularity of Andy Weir's "The Martian" has certainly enlivened the discussions. But, too frequently, the discussion is framed as a moon-Mars, Us-Them, Either-Or debate. Both the moon, as our nearest neighbor, and Mars, next nearest after the moon, are key steppingstones to humankind becoming an interplanetary species.

We need to explore, and perhaps settle, both. In order. And, to go on from there. We are at the beginning, not the end. Yes, the United States has landed astronauts on the moon before — between 1969 and 1972. Perhaps that is why, when NASA and U.S. President George W. Bush announced in 2005 that the Constellation program will go back to the moon and on to Mars, it fell a bit flat. The program ran for a few years, with significant funding shortfalls, and was eventually canceled by the administration of President Barack Obama, which said, famously, of the moon: "Been there, done that."

Article continues belowBut the fact is, the vast majority of people in the world have never been there, never done that. Of Earth's 7.3 billion citizens, 5.1 billion were born after the Apollo program. The number of people who actually know how to get people safely to the moon and back is infinitesimally small, and getting smaller every day. [40 Years After Moon Landing: Why Is It So Hard to Go Back? ]

What we really need is a new generation of explorers who can handle the moon, before biting off the enormous costs and risks of sending people to Mars.

Where is the United States now? It has a somewhat vague, asteroid-retrieval mission. Or, rather, we think we are planning to take a boulder off an asteroid robotically, to put it into Earth-lunar space. Then, sometime around 2023, our new Orion spacecraft will fly a few formation flights with said boulder. Then, very vaguely, we might go on to Mars in the 2030s, if subsequent presidential administrations pick up the can that the current political leadership has kicked down the road.

In 1989, President George H.W. Bush proposed the Space Exploration Initiative, which included landing U.S. astronauts on Mars by 2019. We had a president and a budget director then who were pro-human-spaceflight exploration. However, the U.S. Congress was not so enthusiastic. Also in 1989, 2019 seemed an awful long way off. With the tepid reception, the initiative drifted into oblivion as Bush 41 failed to win re-election in 1992. [50 Years of Presidential Visions for Space Exploration ]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It is an open secret that China plans to send astronauts to the moon, perhaps in the 2020s. A few weeks ago, the European Space Agency (ESA) announced that they have been talking with Russia about a joint program to send Russian and European astronauts to the moon.

Where would all of this leave the United States — a country that currently doesn't even have the capability of launching astronauts into orbit? Answer: Nowhere, realistically.

Interest in the Asteroid Retrieval Mission (ARM) is tepid at best — although it will enable a few technology developments, and some opportunity to shake down the new Orion and Space Launch Systems. But, because current political leadership didn't embrace lunar missions — for reasons that remain unclear — the United States took on much higher risk in saying that we would do an asteroid mission and then go to Mars.

How did that increase risk? By bypassing the logical testing ground of the moon. Once a spacecraft performs the trans-Mars injection burn, there will not be enough fuel to turn around if there were some kind of hardware, or other, failure. Thus, we had better make sure that the hardware works. Where better to test this hardware, off-Earth, than the nearby moon (three days away)? We would wring out the hardware, develop operations and train crew. Then, we would be ready to mount an astronaut mission to Mars.

Human spaceflight has been an international endeavor for some years now. The International Space Station (ISS) is a shining example of bringing former enemies together to successfully build the most audacious space construction project, by far, in the history of the world. The United States can, and should, claim its rightful and logical position as the leader of the new effort to return humans to the moon. This is how we would regain our leadership in human spaceflight, how we retain our space leadership position in the world.

It's time to make some bold decisions and commitments for the future. Our investments in Orion, the Space Launch System, and especially, in robust new commercial space capabilities, position the United States to make real decisions on human spaceflight.

We are ready to define the future; we are ready to lead. Let's not let the moment pass us by.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Leroy Chiao is a former NASA astronaut and International Space Station (ISS) commander. Chiao holds appointments at Rice University and the Baylor College of Medicine. Chiao has worked extensively in both government and commercial space programs, and has held leadership positions in commercial ventures and NASA. Chiao is a fellow of the Explorers Club, and a member of the International Academy of Astronautics and the Committee of 100. Chiao also serves in various capacities to further space education. In his 15 years with NASA, Chiao logged more than 229 days in space, more than 36 hours spent in Extra-Vehicular Activity (spacewalks). From June to September 2009, he served as a member of the White House appointed Review of U.S. Human Spaceflight Plans Committee, and currently serves on the NASA Advisory Council. Chiao studied chemical engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in 1983. He continued his studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara, earning his Master of Science and Doctor of Philosophy degrees in 1985 and 1987. Prior to joining NASA in 1990, he worked as a research engineer at Hexcel Corp. and then at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Livermore National Lab. Dr. Chiao left NASA in December, 2005 following a 15-year career with the agency. Chiao studied chemical engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in 1983. He continued his studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara, earning his Master of Science and Doctor of Philosophy degrees in 1985 and 1987. Prior to joining NASA in 1990, he worked as a research engineer at Hexcel Corp. and then at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Livermore National Lab.