Volcanoes on Venus May be Young and Active

New evidence for recently active volcano hotspots on Venus likethose that created the Hawaiian Islands has been found in new observations by aEuropean spacecraft.

These relatively young and potentially active surfacefeatures could give scientists clues to how the planet has resurfaced over thelast billion years, which in turn could help better understand the interiordynamics of Venus, as well as climate change on Earth's nearest neighbor and onEarth itself.

The hotspots on Venus'hellish surface were first recognized by NASA's Magellan spacecraft, whichentered into orbit around the planet in 1990. These hotspots stood out becausethey had a distinctive rise in topography, volcanic centers and telltalegravity signatures.

The hotspot sites were the most likely candidates for recentvolcanicactivity on the surface of Venus ? the question of whether or not Venus'surface is geologically active has been a major one in studies of the planet ?but just how young the features were was unclear.

"We were getting warm there, but not actuallyhot," said Suzanne Smrekar of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory inPasadena, Calif., and a member of the team that analyzed the new observationstaken by the European Space Agency's Venus Express probe.

Young lava flows

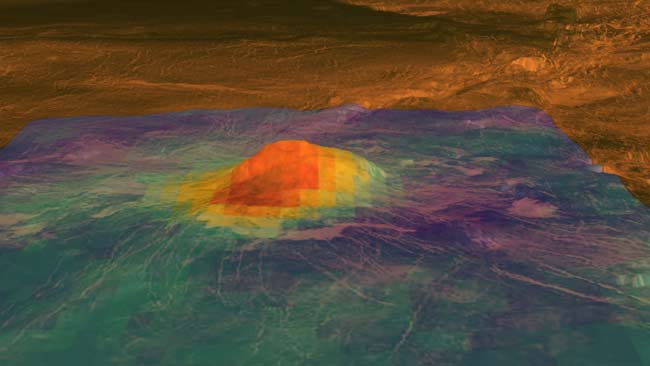

An instrument aboard Venus Express, ESA's first probe toVenus, mapped thermal emission from the southern hemisphere of Venus, whichindicate differences in the composition of the surface. Unusually highemissions patterns were seen around the only three of the nine known hotspotsthat Venus Express could image, the Imdr, Themis and Dione Regiones.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Surface regions that are old would be expected to have lowemissivity patterns because of long exposure to weathering from Venus' harshatmosphere.

So the high emissivity of these hotspots and the evidence from Magellan"all point to the fact that these are recent [volcanic lava] flows,"Smrekar told SPACE.com. [ Seethe surface of Venus.]

Exactly how young the features are is hard to pin downbecause of limited information about the environment at Venus' surface and thecomposition of its lower atmosphere, but Smrekar and her colleagues estimatethat the lava flows are younger than 2.5 million years, possibly even as youngas a few hundred to tens of thousands of years old.

To pin down the age of the flows would likely take a landerto the Venusian surface, last visited by the Soviet Venera probes in the early1980s, to get better measurements of conditions there, which would aide labexperiments that try to mimic weathering processes on the sweltering planet'ssurface.

Resurfacing question

The young age of the hotspots has implications forunderstanding how Venus might have been resurfaced.

Magellan data showed that the surface of Venus had fewcraters; since it is known that the solar system has undergone periods of heavybombardment in the past that are still visible on ancient unchanged surface,such as that of Earth's moon, the evidence suggested that Venus had beenresurfaced since then.

One suggestion to explain the resurfacing is a catastrophicevent that would have buried the planet's surface under about 1 mile (1.6 kilometer)of lava and caused by unknown, exotic interior processes unlike those thatoperate within the Earth. They also imply that "Venus would have had to beessentially dead since then," Smrekar said.

The other idea for Venus' resurfacing is a more gradual,small-scale process that would imply that volcanism was still happening todayand that Venus had an interior more like Earth's, though Venus would still lackEarth's surface-reshaping plate tectonics.

The estimated young age of the hotspots suggests that thelatter is the case on Venus and that the planet "doesn't have to have hadthis exotic resurfacing event," Smrekar said.

Climate change, exoplanets and bright spots

A volcanic eruption was put forward as a possibleexplanation to a strangebright spot seen in the atmosphere of Venus last year. Smrekar and severalof her colleagues are following up on this event to see if a volcanic eruptionfrom one of these hotspots coincides with the spot and could feasibly explainit. If it does and can, then that link could be even more evidence that Venus'volcanoes are still active.

"We're kind of going from warm, warmer, warmest tomaybe really hot," Smrekar said.

Determining whether or not Venus is still active and whatkind of processes govern its interior could also help scientists betterunderstand what kind of planets might potentially be orbiting other stars.

"It's a great laboratory for understanding terrestrialplanets," Smrekar said. "What's really the anomaly [among theseplanets] ? is it Venus, or is it the Earth?"

Understanding the processes at work on Venus, in particularvolcanic eruptions, can also help scientists better understand climate change,both on Venus and on Earth, Smrekar said, because volcanoes spew gases into theatmosphere that can change the composition of the atmosphere and the amount ofsunlight that hits a planet's surface.

The new observations are detailed in the April 8 issue ofthe journal Science.

- Top10 Extreme Planet Facts

- Images- Beneath the Clouds of Venus

- Images- Postcards from Venus

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.