Space Colonies Will Start Out Like the Wild West, Grow Family-Friendly

As humans explore other worlds, the colonies they develop may change over time. While the first settlements may rely on individuals, as the outposts grow more self-sustaining, families will likely become the colonists of choice, a panel of experts said.

"The socioeconomic origins of colonists are going to change over time," science fiction author Charles E. Gannon told Space.com.

Earlier this year at Dragon Con in Atlanta, Gannon was part a panel of scientists and science communicators who discussed how future space colonies might look and act, and how such developments might affect the rest of humanity on Earth. Gannon was joined by nuclear physicist Ben Davis, forensic anthropologist Emily Finke, science teacher Lali DeRosier and moderator Kishore Hari, a self-described "professional nerd." [NASA's Wild Space Colony Concepts in Images]

"Trailblazers will be specialists; so will true pioneers. However, once you move to a settler model, things will change to a more normalized selection demographic," Gannon said in an email interview.

From individuals to families

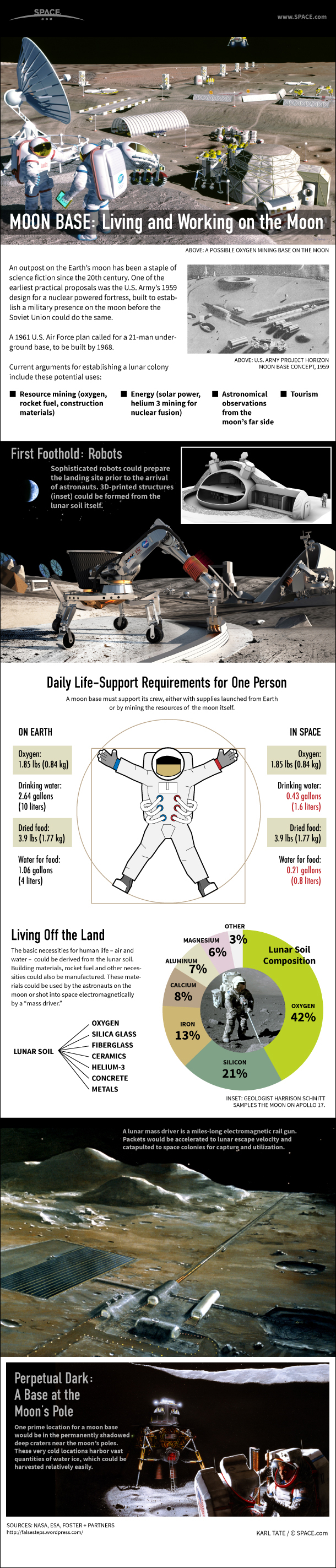

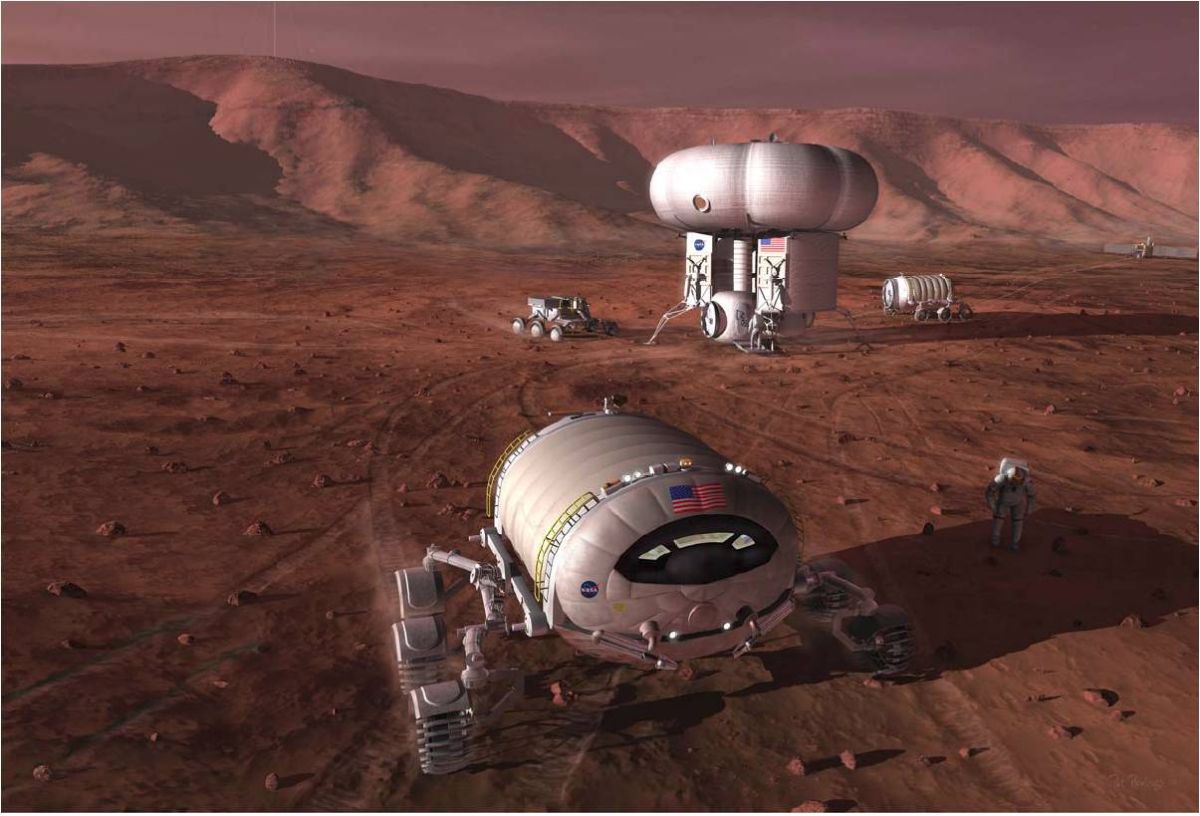

Initially, space colonization may function a great deal like the American West. The first forays into the wilderness were made by travelers like Lewis and Clark, individuals who cut their way across the country to map it for those who stayed behind. The intrepid explorers had to carry their own supplies, all fabricated back home. The panel likened this sort of exploration to visits to the moon and Mars by small groups of astronaut explorers.

"Mars is a piece of cake compared to other bodies," Hari said during the session.

The initial stages of colonization would most likely be conducted by workers who would build the necessary support systems, the panelists said. This idea led to a vigorous discussion about who those workers might be. An audience member asked if the first colonists would be the wealthy elite, but the panelists quickly dismissed this, saying the group would more likely rely on blue-collar workers skilled at hands-on labor.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"You put a bunch of college professors on a spaceship, and nothing's going to get done," Davis quipped.

"They'll form a committee," Gannon added.

Finke pointed out that the original American settlers consisted of a diverse group, including laborers, priests and scholars. The first space settlers might have a similar makeup. [SpaceX's Mars Colony Ship Concept in Pictures]

"Expect a working middle class for a while," Gannon said. "The wealthy will manipulate from safer, easier environments, and the poor are unlikely to have the necessary skill sets that warrant someone else paying a ticket for them."

But that would change over time, the panelists predicted.

As the colony moved toward self-sustainability, the type of settlers would change. Instead of plucky individuals setting down roots, settlers might consist of parents willing to brave the new frontier with families. Over time, the colonies would look more like frontier towns than collections of individuals.

Of course, families settling the West could make the journey fairly cheaply compared to taking a rocket to a new planet. While a space colony is still young and tethered to Earth, the home planet might have a vested interest in screening hopeful travelers, panelists said.

The panel debated the difficulty of screening a young family before sending them into space. Would hopeful colonists first be sent to Antarctica with their small children to see how they cope with the isolation? While physical health could be screened for when a person was young, how does one rate the social ability of a 2-year-old?

The group agreed that some method of screening would need to be applied, though Gannon said that once the colony was safe, such screening could be minimal.

"If you didn't do that, you're buying yourself potentially huge trouble on the back end," Hari said, referring to a screening process.

Untethered from Earth

Like in the Old West, the goal would be for the colony to become self-sustaining, the panel said. Once a colony could support itself, it would no longer need to rely on materials from Earth to survive. When asked if an organization on Earth could realistically hope to control what was happening on Mars, Davis said, "If they're still getting their caloric intake from someplace else, yup, you can." [Poll: Where Should Humanity Build Its First Space Colony?]

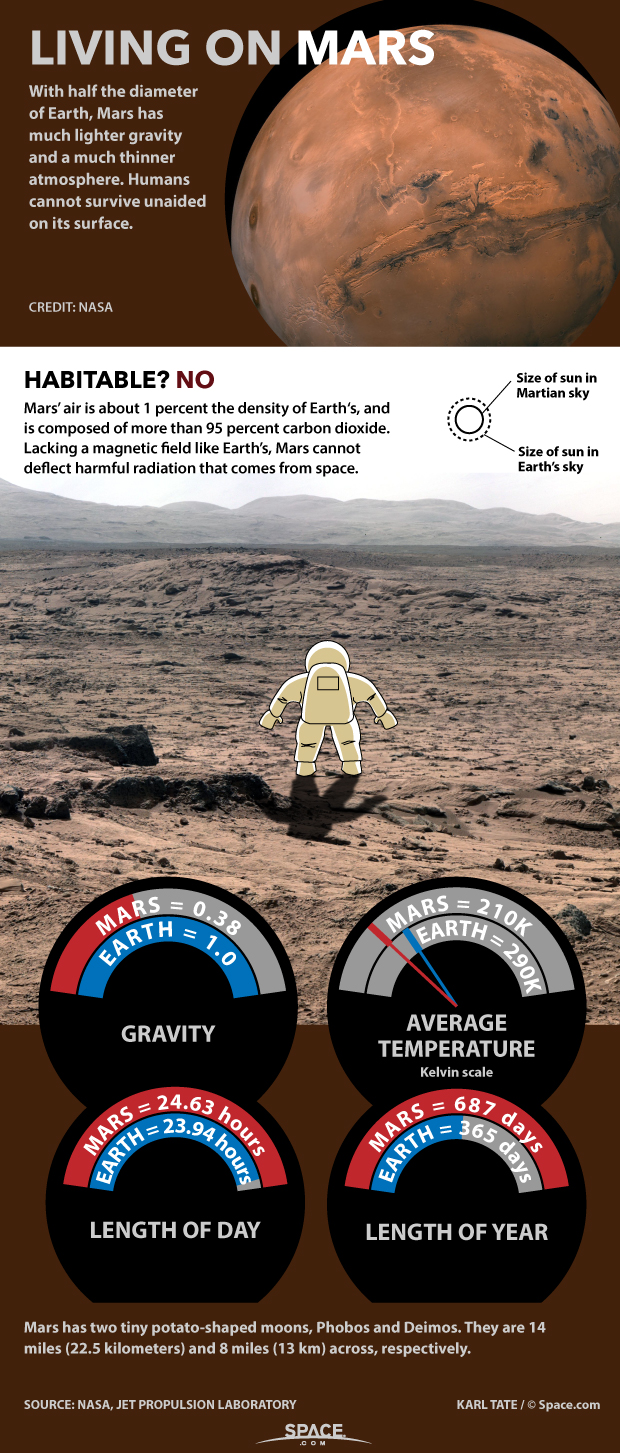

Gannon named the biggest challenge facing a colony that aimed to grow independent from the people back home: the supply of volatiles, particularly oxygen and water. The first explorers would need to find a way for colonists to harvest those on the new world, Gannon said.

"If you have to ship those to the colony, it will be both economically and physically dependent and probably never be profitable or really safe," Gannon said.

Even if an underground colony relied on rocks to shield itself from deadly radiation, it would still need enough water for similar shielding during vehicular missions, he said, making ice harvesting crucial to the colony's survival.

"There are plenty of other [challenges]," he said. "But this is the minimum ante for long-term self-supportability."

Building a new life

What it means to be self-sustaining would also be up for debate. While food, water and oxygen are all obvious things a colony would need to support itself, less clear are things like medicine and computers.

"The colony would ask the question early on what it values," Davis said. At that point, the colonists may seek to become fully independent from Earth, much like many of England's colonies did from the home country, Davis said. Each colony might approach its negotiations for materials differently, he said. "They'll find that out [what they value], and play political judo."

An effort to become self-sustaining would most likely affect colonial education. Instead of focusing on traditional schoolhouse learning, education might be more likely to follow family or professional lines, the panelists said. Children might serve as apprentices for other laborers or be taught the family trade. Instead of teaching broad concepts, education would more likely focus on learning specific trades.

The panelists named another requirement for full independence that Earth's colonists never had to worry about: genetic diversity.

Finke said the minimum viable human population is around 10,000. That doesn't mean a young colony would require 10,000 people to be self-sustaining. She suggested instead that a small population with a large sample of frozen embryos and sperm samples would be less expensive to send than a larger population.

Automation would also play a key role in a colony's survival. While humans require resources to survive, robots and automatons could potentially do many of the jobs without the same demand. The panel envisioned such machines playing a key role, particularly in early colonization. How dominant a part they play would depend a great deal on progress, Gannon said.

"Robotics is a wild card here," Gannon said.

Does humanity dare?

Contamination of other worlds would also be a significant concern in colonization. To close out the session, Hari asked the room if humans have the right to potentially damage another planet after proving to be such poor caretakers on Earth. Half the room said they thought humans should colonize other worlds, while a handful of people remained concerned.

"If humanity doesn't have the 'right' to exist, who sits in judgment?" Davis wondered. He pointed to the survival instinct that has brought humans to their current state, and the possibility of an event that could kill off the human population, such as an asteroid or comet impact.

But humans could do even more damage than depleting a world of natural resources and leaving behind a barren wasteland. People could inadvertently kill off an undetected life-form, which raises important moral issues, panelist said.

That may be more than just a question of politics or ecology. Gannon pointed out that contamination could be a two-way street, with results not immediately evident or consequential. He gave as an example the idea that an Earth-based bacteria like Escherichia coli (E. coli), found in the human gut, got loose on the surface of the world whose native life-forms had been overlooked for one of any number of reasons. It could take alien life 50 years to reject, attack or incorporate the bacteria. Or the life-form could simply learn how to break down the bacteria and eat it.

"But that means we've just taught the local microorganisms how to break down and eat something native to our biosphere," Gannon said. "We could be next on the menu, because our carelessness provided that advance learning."

Humans need to tread carefully, he said.

"The key question of the future is how to expand ethically," Finke said. "We need to expand in a way that does as little harm as possible to the environment."

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd, Facebook or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky