Appendages Help Microbes Survive Harsh Conditions

The most ancient kinds of microbes on Earth often have special filaments lining their surfaces. Scientists are discovering that these structures can play a variety of roles in helping microorganisms survive the most hostile environments on Earth, findings that could shed light on how alien life might withstand extreme conditions on distant worlds.

The most complex forms of life on Earth nowadays are eukaryotes, organisms whose cells possess nuclei. However, the first life on Earth were prokaryotes, single-celled microorganisms that do not have nuclei. There are two kinds of prokaryotes — the familiar bacteria, and the archaea, many of which thrive in harsh environments such as hot springs, salt lakes, underground petroleum deposits and deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

Scientists have discovered a number of prokaryotes that could potentially withstand many of the same extreme conditions found on Mars and other distant planets. A better understanding of how bacteria and archaea survive these dangerous habitats might yield insights into the adaptations that could make life on other worlds possible, said Mechthild Pohlschroder, a microbiologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. [Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

Pohlschroder and her colleague Rianne Esquivel detailed their researchin the March 2015 issue of the journal Frontiers in Microbiology. Their researchwas supported by a grant from the Exobiology & Evolutionary Biology element of the NASA Astrobiology Program.

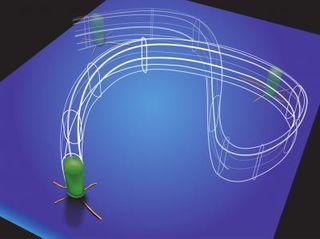

A class of protein structures known as type IV pili (T4P) are filaments found on the cell surfaces of species in nearly all known major groups of prokaryotes. This prevalence suggests that these appendages are extremely ancient in origin, Pohlschroder said.

"Because these appendages are found on many archaeal and bacterial species, spanning a broad array of organisms in both prokaryotic domains of life, it's likely that they had important roles to play in the common ancestor of the bacteria and the archaea" Pohlschroder said.

Indeed, these structures might have played a major role in the survival of these microbes, helping them flourish for millions of years, she added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

T4P are filaments composed of small proteins known as pilins that link together to form helical fibers. Pilins all contain short segments called signal peptides that help the pilins get incorporated into T4P. Although pilins can differ greatly across species, their signal peptides are structurally similar to each other, indicating common origins, Pohlschroder noted.

Although T4P are often relatively simple structures, researchers are discovering that bacteria and archaea have adapted T4P to play an extraordinarily diverse set of roles.

"Amazingly, although many cell appendages are adapted, to an extent, to efficiently perform a single function, T4P are quite versatile, and can, depending on local conditions, serve many and varied functions,” Pohlschroder said.

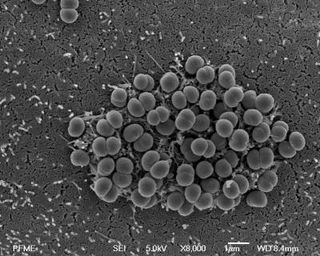

One key role T4P plays involves adhesion. Sticking onto surfaces can help prokaryotes either colonize fertile new habitats or cluster together in slimy fortresses known as biofilms to withstand potentially lethal hazards such as ultraviolet radiation, desiccation, antibiotics and toxins, Pohlschroder said.

In addition to adhesion, many T4P have evolved to carry out additional functions, such as movement. For example, in many archaea, a kind of T4P sometimes known as archaellum or archaeal flagellum, can rotate like propellers and help the microbes swim through the water. Moreover, in some bacteria, T4P can also retract, allowing a twitching form of locomotion.

Different kinds of pseudopili in bacteria can help the microbes secrete proteins. For instance, the cholera bacterium uses T4P to release a compound that helps it colonize human intestines. Some bacteria may even use electrically conductive T4P to get rid of electrons generated as waste as the microorganisms synthesize vital molecules.

"A highly diverse assortment of single-cell organisms produce T4P, including many organisms that inhabit highly variable and extreme environments," Pohlschroder said. "Therefore, it is not surprising that these cellular appendages have evolved along diverse and varied paths to support processes that allow organisms to thrive under a wide variety of extreme conditions, including conditions similar to those that are found in some extraterrestrial environments, such as the highly salty fluids on Mars."

Researchers have found that the functions of T4P depend on small, precise modifications of pilins. Prokaryotes are capable of quickly modifying the pilins they synthesize, "allowing cells to make rapid transitions between living as a free-swimming cell or living within the constraints of a protective biofilm structure, depending on local environmental conditions," Pohlschroder said.

Future research can focus on T4P proteins that help microbes adhere to surfaces or swim through fluid, which could help scientists better understand how these appendages help microorganisms respond to stress, Pohlschroder said. "We will also attempt to determine the specific roles T4P of specific compositions play in various cell processes, especially with regard to the pili that aid in responding to changes in such things as salt concentration or nutrient conditions."

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us