'Stretched Out' Alien Planets Could Be Seen with New Telescopes

As scientists ramp up the search for Earth-size planets outside our solar system, one team says it's possible that "stretched-out" rocky exoplanets could be found orbiting close to their parent stars.

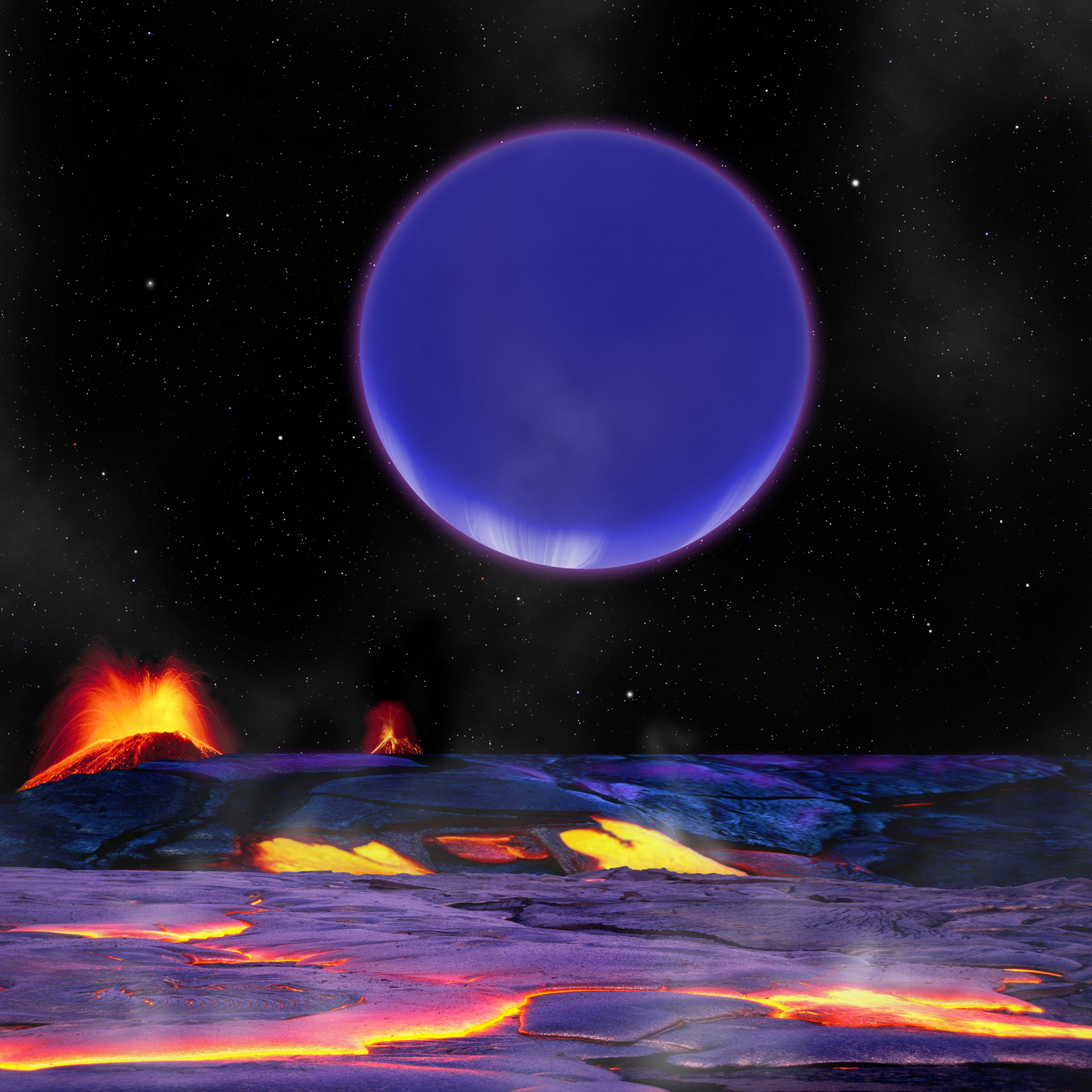

These exoplanets would be extremely hot, bent out of shape by the gravitational pull of their parent stars and likely inhospitable to life. But studying these worlds could shed light on the internal structure of rocky planets, researchers said.

"Imagine taking a planet like the Earth or Mars, placing it near a cool red star and stretching it out," study lead author Prabal Saxena, an astrophysicist at George Mason University, said in a statement. "Analyzing the new shape alone will tell us a lot about the otherwise impossible to see internal structure of the planet and how it changes over time."

Scientists are already familiar with gas giants that orbit close to their parent stars; many such "hot Jupiters" have been discovered to date. Such worlds tend to have high temperatures (more than 1,832 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1,000 degrees Celsius) and experience extreme tidal forces from the star's gravity.

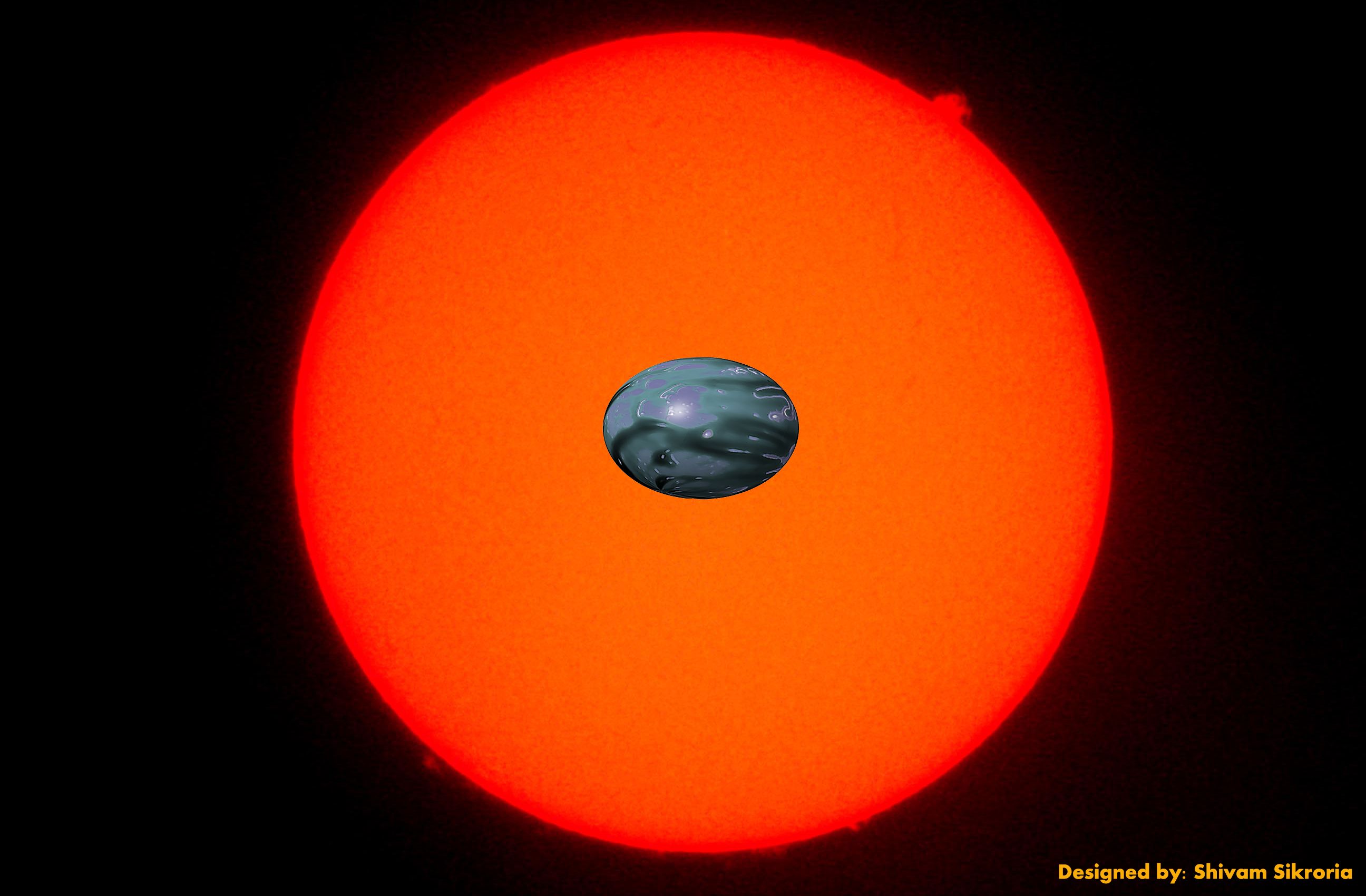

Prabal's team created a model in which rocky planets are similarly close to red dwarf stars, the most common type of star in the galaxy. Because red dwarfs are dimmer than the sun, it can be easier to find planets crossing across their faces and blocking their light — a search strategy known as the transit method.

The model revealed that close-orbiting rocky planets should be tidally locked to their star so that one side always faces its stellar companion, just as the near side of the moon always faces Earth. The star's gravity should also stretch out the core of the planet, making it easier to spot a transit because of the world's unusual shape.

Signals could be detectable by currently operating telescopes, the team added, with a higher probability of success coming from newer telescopes in production. These include NASA's $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope, set to launch in 2018, and the ground-based European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT), which is expected to start observing the heavens in the mid-2020s.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The study was published online this month in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.