5 Exoplanets Most Likely to Host Alien Life

The "most Earthlike exoplanet" rankings will have to be revised.

Today (April 17), astronomers announced the discovery of Kepler-186f, the first truly Earth-size alien planet ever found in a star's "habitable zone" — that just-right range of distances where liquid water could exist on a world's surface.

Kepler-186f is a rocky world just 10 percent bigger than Earth that lies 490 light-years away. It's the outermost of five planets known to orbit Kepler-186, a red dwarf star that's considerably smaller and dimmer than our own sun. More than 70 percent of the Milky Way's 100 billion or so stars are red dwarfs. [9 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

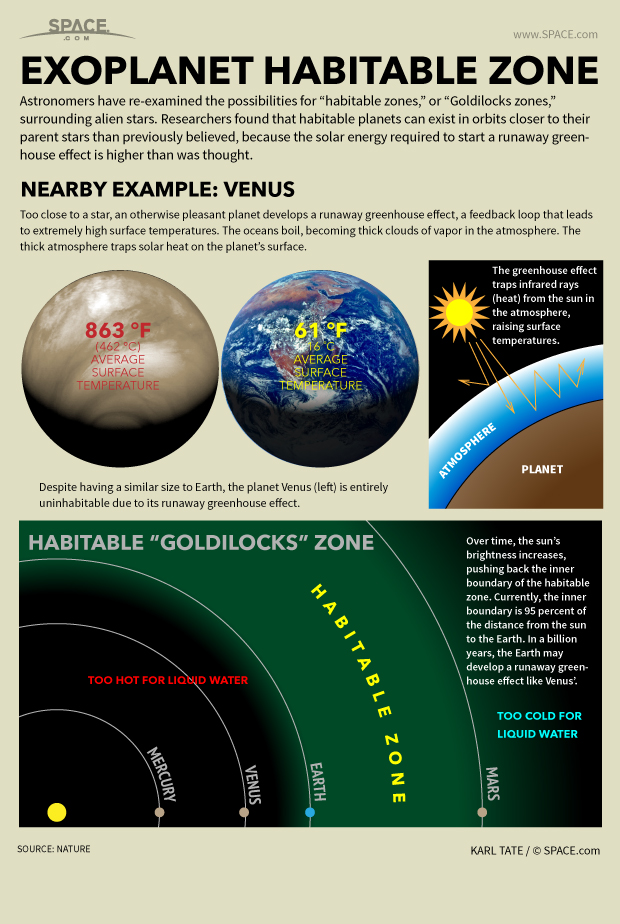

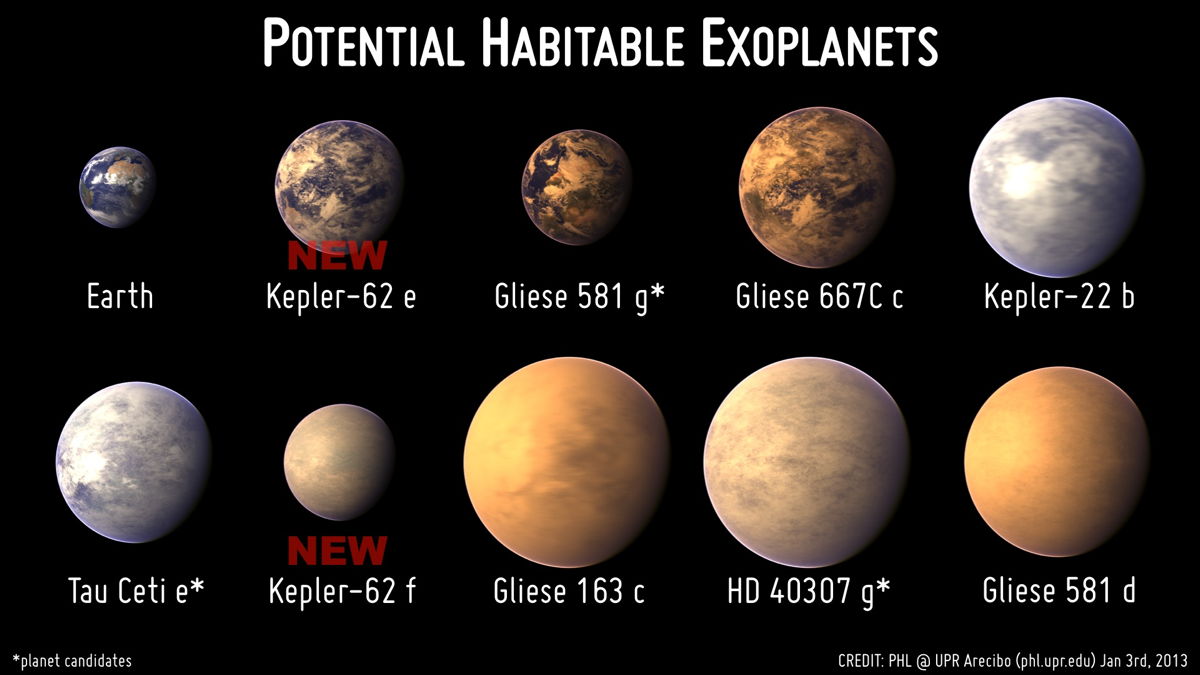

The Planetary Habitability Laboratory, run by the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo, maintains a database of all exoplanets that may be capable of hosting life as we know it. Here's a quick look at the other worlds in PHL's top five (assuming Kepler-186f claims the first spot):

2. Gliese 667Cc

This "super-Earth" is at least 3.9 times more massive than our own planet. It orbits the red dwarf Gliese 667C, which is part of a three-star system that lies 22 light-years away, in the constellation Scorpius.

Gliese 667Cc completes one lap around its parent star every 28 days. The planet has one confirmed neighbor, a world called Gliese 667Cb. But astronomers have spotted five additional planet candidates orbiting the star as well.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

3. Kepler-62e

As its name suggests, Kepler-62e was discovered by NASA's Kepler space telescope. About 1.6 times more massive than Earth, the planet lies about 1,200 light-years away, in the constellation Lyra. It completes one lap around its parent red dwarf every 122 days.

Kepler-62e is one of five planets known to orbit the star Kepler-62. Researchers think Kepler-62e and its potentially habitable neighbor, Kepler-62f, are "water worlds" — warm places mostly or completely covered by liquid water.

4. Kepler-283c

Another Kepler find, Kepler-283c is about 1.8 times bigger than Earth and completes one orbit every 93 days.

The planet is one of two worlds known to circle the star Kepler-283, which is just over half as wide as Earth's sun. The other planet in the system, Kepler-283b, lies much closer to the star and is thus probably too hot to host life..

5. Kepler-296f

This planet is the outermost of five confirmed worlds circling Kepler-296, a star that's about half the size of Earth's sun and 5 percent as bright. At 1.8 times the size of Earth, this planet completes one orbit every 63 days.

Kepler-296f is one of 715 confirmed planets just announced in February by the Kepler mission team. The spacecraft has spotted 3,845 potential planets, with 961 confirmed by follow-up observations or analysis. Mission officials expect that about 90 percent of Kepler's detections will turn out to be the real deal.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.