Space Station's Coolant Leak: 10 Questions (and Answers)

Astronauts aboard the International Space Station noticed a serious leak of ammonia coolant fluid on Thursday (May 9). NASA is still investigating the problem and a potential solution. Here's what we know now:

When did this problem first begin?

An ammonia coolant leak was first discovered on the station in 2007. At that time the leak was so slow it didn't require immediate action. During a November 2012 spacewalk, two NASA astronauts rewired coolant lines and installed a spare radiator in an attempt to stop the leak, which appeared to succeed, for a while.

When did astronauts notice the leak had worsened?

On Thursday (May 9), around 11:30 a.m. EDT (1530 GMT), the crew on the International Space Station noticed a stream of white flakes — frozen ammonia coolant — coming from the same area as the original leak. [Graphic: How the Space Station's Cooling System Works]

Are the astronauts in danger?

NASA officials say the leak poses no danger to the six-person crew of the space station.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

What can be done to stop the leak?

NASA astronauts Tom Marshburn and Chris Cassidy may venture outside the station on an emergency spacewalk Saturday (May 11) to investigate the problem and attempt a repair. NASA officials have not yet made an official decision on the spacewalk, and are still investigating options.

Where is the leak located?

The leak appears to be coming from the space station's Port 6 truss, part of the scaffolding-like backbone of the orbiting laboratory.

What is the ammonia coolant used for?

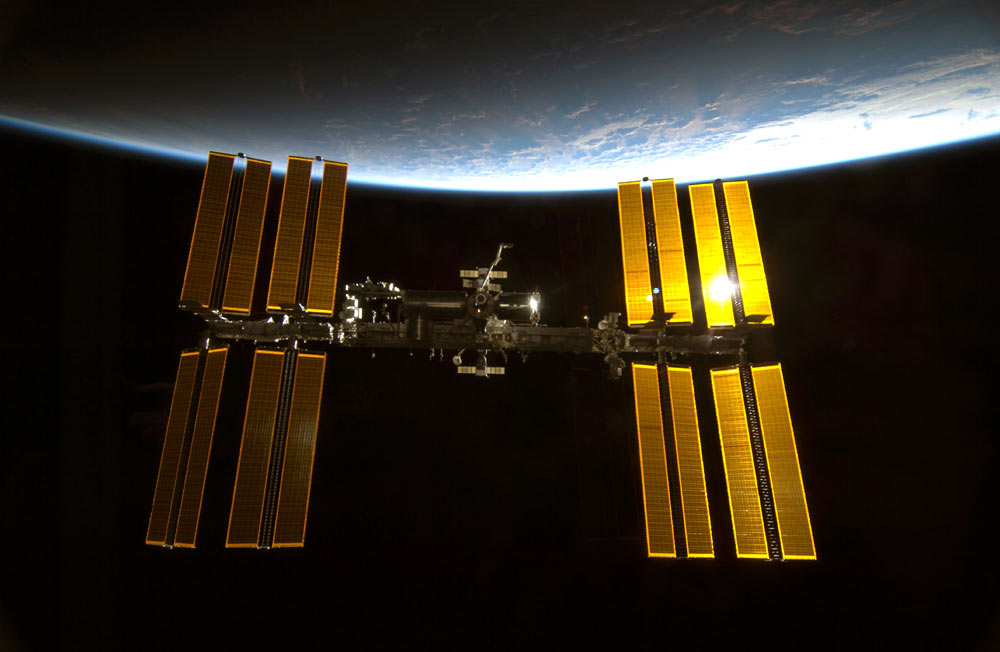

Liquid ammonia is used to cool the power systems on each of the space station's eight giant solar array panels, which must stay chilled to operate. These systems convert energy from the sun into electricity to power the orbital outpost. The coolant system is officially called the Photovoltaic Thermal Control System (PVTCS).

How does the coolant system work?

Liquid ammonia is an efficient transporter fluid for heat. It is used on the International Space Station to absorb heat generated from electronic equipment and transfer it to radiator panels that dissipate the heat into space. This keeps the electronic power systems on the solar arrays cool, so they can convert energy absorbed from the sun into usable electricity for the space station

Is this the same leak as the one noticed in 2007?

Right now it's unclear whether the same leak that was addressed in the 2012 spacewalk has worsened, or if the same ammonia coolant loop has sprung a new leak.

What can cause coolant leaks?

In the case of the earlier leak, NASA engineers suspected that the system might have been damaged by a micrometeoroid impact. Tiny bits of rock or debris in orbit can be dangerous because of their great speed.

Has the coolant system ever acted up before?

In an unrelated issue in July 2010, an electrical short shut down one of the two 780-pound (353 kilograms) pumps that move the liquid ammonia coolant through loops around the station. During a series of complex spacewalks, astronauts replaced the failed pump with a spare, which fixed the problem.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.