Milky Way's Black Hole to Gobble Space Cloud This Year

The giant black hole at the center of the Milky Way is preparing to gobble up a tasty gas cloud in a cosmic meal astronomers are eager to witness.

Most galaxies are thought to host humongous black holes at their cores, and the Milky Way's, which is called Sagittarius A* (pronounced "Sagittarius A-star") contains about 4 million times the mass of our sun.

It's about to add a tiny bit more mass to its girth, when it swallows a cloud on a collision course with it. Scientists think it will take the black hole about a year to completely devour the cloud, with the peak of its feast occurring around September of this year.

"This is the first chance we've had to witness such an event in nearly 40 years of monitoring the galactic center, so this is a rare privilege," said P. Chris Fragile, an astrophysicist at the College of Charleston who works on computer simulations of the cloud's fall. The phenomenon, he said, "will be one of the most carefully observed astronomical events ever."

In contrast to the enormous size of the black hole, the cloud is just about three times the mass of Earth — "just a tiny little snack," said Stefan Gillessen, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany. [Milky Way Black Hole Eats Gas Cloud (Video)]

Gillessen and his colleague Reinhard Genzel have been observing the cloud and plan to ramp up their observations soon to catch its descent toward the black hole. Observing the event will require some of the most sensitive observatories on Earth, such as the Very Large Telescope in Chile, where Gillessen and Genzel will be making their observations.

"It's at the limit of what telescopes can do," Gillessen told SPACE.com. "It's very faint, and we have to look for quite some time to see it."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

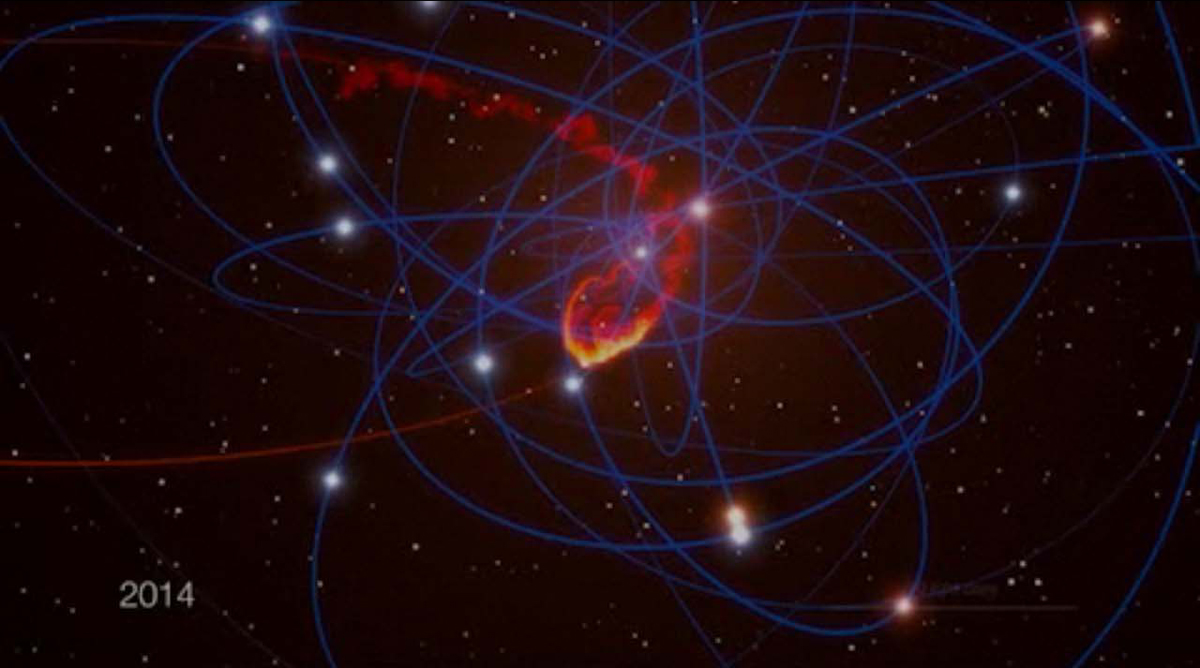

Already, scientists have seen the cloud speed up and stretch out as it gets pulled closer and closer to its doom. Gravitational tidal forces from the black hole have caused it to morph from a roughly circular shape, in 2004, into a thin, oblong object in 2012. And while eight years ago the cloud was moving about 620 miles per second (1,000 kilometers per second), it is now zooming at a brisk 1,500 miles a second (2,500 km/s).

The upcoming cosmic spectacle should offer scientists a chance to test some of their theories about how black holes pull in, or accrete, mass.

"It might be a very unique opportunity to see how it is accreting," Gillessen said. "The most exciting thing would be if Sagittarius A* changes its accretion state. If the accretion rate increases, you might expect that Sagittarius A* itself will turn significantly brighter, and it might also change its structure. There's a slight chance that radio telescopes can actually catch that."

Scientists also hope to learn more about the cloud and where it came from. For example, some theories suggest there could be a hidden star buried beneath the gas that is currently invisible, but which is feeding the cloud with gas from within.

"We can obviously learn more about the nature of the cloud itself, we can learn about the conditions of the background gas, and ultimately we can learn more about how the black hole at the center of our galaxy is really fed," Fragile said.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. This article was first published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.