My Date With R2: Reporter Meets NASA's Strong, Silent Space Robot

HOUSTON — To call NASA's Robonaut 2 the silent type would be an understatement.

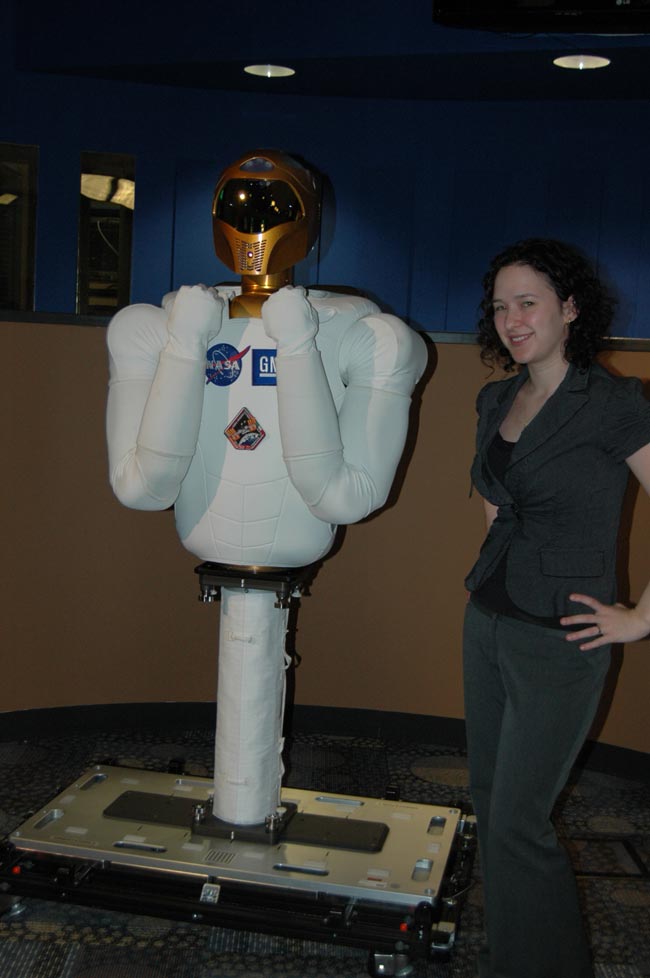

The first humanoid robot headed for space is no chatty C-3PO. In fact, when two red-shirted NASA handlers rolled R2 — short for Robonaut 2 (not R2D2) — into the press area here at Johnson Space Center, the process was so quiet I didn't even notice.

Which made looking up from my notes a bit of a shock. At 330 pounds (almost 150 kg), Robonaut 2 is a big piece of machinery, and he (it's almost impossible not to think of it as a "he") looked rather intimidating looming across the room like a boxing dummy in a spacesuit. [Photo: Me and Robonaut 2]

The robot's "tucked and ready for launch" position only exacerbated the effect. With his bulky arms pulled into his chest, R2 seemed ready to throw a punch.

But Robonaut 2 isn't a fighter. The robot, developed by NASA in partnership with General Motors, is designed to help astronauts with chores and repairs aboard the International Space Station. NASA plans to launch R2 to the space station next week aboard the space shuttle Discovery, along with six flesh-and-blood astronauts and a cargo pod that eventually will be used as a closet on the orbiting lab.

This Robonaut 2 graphic gives you a glimpse of what the robot is expected to do.

According to developer Rob Ambrose, the acting chief of the Automaton, Robotics and Simulation Division at Johnson Space Center, making sure Robonaut 2 can't hurt anyone was the primary goal of the development team.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"When a person steps in the way and interferes with it, nothing dangerous is going to happen," Ambrose told reporters Oct. 21. "The robot will just pause. And if you hit it really hard, it will turn itself off."

Okay, so I didn't have to worry about R2's left jab.

In fact, the model I met was a prototype, Robonaut 2A. He is mechanically identical to Robonaut 2B, the version that's packed and ready for the launch. The only things different, his handlers told me, are the materials he's made of.

Materials are important aboard the space station. They can't be flammable, for one thing, so Robonaut 2A's soft Lycra and neoprene covering was replaced by fire-resistant spacesuit material for the ISS-bound model. Some of the R2B unit's electronic components are space-friendly, as well.

Anything going aboard the space station also has to be odor-free: That new-car smell of off-gassing plastics might be appealing on Earth, but in the enclosed chambers of the space station it doesn't fly.

To make sure the emission of gases wouldn't be an issue, R2's developers took him to White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico and baked him in a giant oven for four or five days. Then they ran the air in the oven through a mechanical sniffer to make sure it was clean.

Robonaut 2B passed the test and won a trip to space.

R2A, on the other hand, is destined to remain earthbound as the development team tests out lower bodies they hope will enable the R2B to move about the space station. (The Robonauts have only upper bodies.)

They're also working on giving the robots wheels so they can one day roam the moon or explore distant planets.

For now, both R2 models are stuck in place on aluminum posts. From that vantage, R2A stood stoically last week as Ambrose showed videos of the robot lifting weights (humans are stronger and faster, Ambrose said, but the machines beat us in endurance) and moving its arms in graceful patterns.

Before Robonaut 2A was wheeled out of the room, I came closer to peer into his dark visor. "He doesn't bite," a handler promised.

I didn't tell him I was more concerned about somehow breaking the $2.5 million machine, but I did ask if I could touch R2A.

Permission granted, I squeezed the robot's bicep. It felt like a cross between a memory foam pillow and a well-muscled human arm.

He may not be much of a conversationalist (except on Twitter as @AstroRobonaut), but I can see the appeal of having the strong, silent type around to do the tedious work of space exploration.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.