NASA Will Launch a Laser Into Space Next Month to Track Earth’s Melting Ice

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

NASA is preparing to launch a cutting-edge, laser-armed satellite that will spend three years studying Earth's changing ice sheets from above.

Called the Ice, Cloud and Land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2), the mission is currently scheduled to launch in mid-September. The satellite will be able to measure the changing thickness of individual patches of ice from season to season, registering increases and decreases as small as a fifth of an inch (half a centimeter).

"The areas that we're talking about are vast — think the size of the continental U.S. or larger — and the changes that are occurring over them can be very small," Tom Wagner, a NASA scientist studying the world's ice, said during a news conference yesterday (Aug. 22). "They benefit from an instrument that can make repeat measurements in a very precise way over a large area, and that's why satellites are an ideal way to study them." [How NASA Is Tracking Earth's Melting Arctic Sea Ice (Video)]

While the mission is optimized for studying ice at the poles, its data should also aid scientists studying forests around the planet.

ICESat-2, which cost a little over $1 billion and is about the size of a Smart car, will follow two previous major NASA projects to monitor ice thickness.

In 2003, the original ICESat began seven years of laser-aided measurements of ice height, bouncing a single laser off the surface of the ice. Because ICESat-2 wasn't ready to launch when the original mission ended, NASA designed a stopgap airplane-based mission called Operation IceBridge to track particularly crucial areas of ice.

NASA has excelled at measuring the area ice covers for decades now, watching ice sheets shrink and grow in two dimensions as the seasons change and the planet warms. But as anyone who has held an ice cube knows, ice comes in 3D, and space-based cameras struggle to measure that third dimension — hence, the lasers.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So far, those lasers have brought disturbing news. "What ICESat found is that the sea ice is actually thinning," Wagner said. "We've probably lost over two-thirds of the ice that used to be there back in the '80s."

The new spacecraft will produce much more detailed data than the original mission and more constant data than IceBridge.

"ICESat-2 really is a revolutionary new tool for both land ice and sea ice research," Tom Neumann, NASA's ICESat-2 deputy project scientist, said during the news conference. Sea ice is particularly complicated, since the laser must measure the difference between ice surface and ocean surface, which can be just a few centimeters apart. "It really is an incredible engineering feat, but it's one that the science critically depends on," he said.

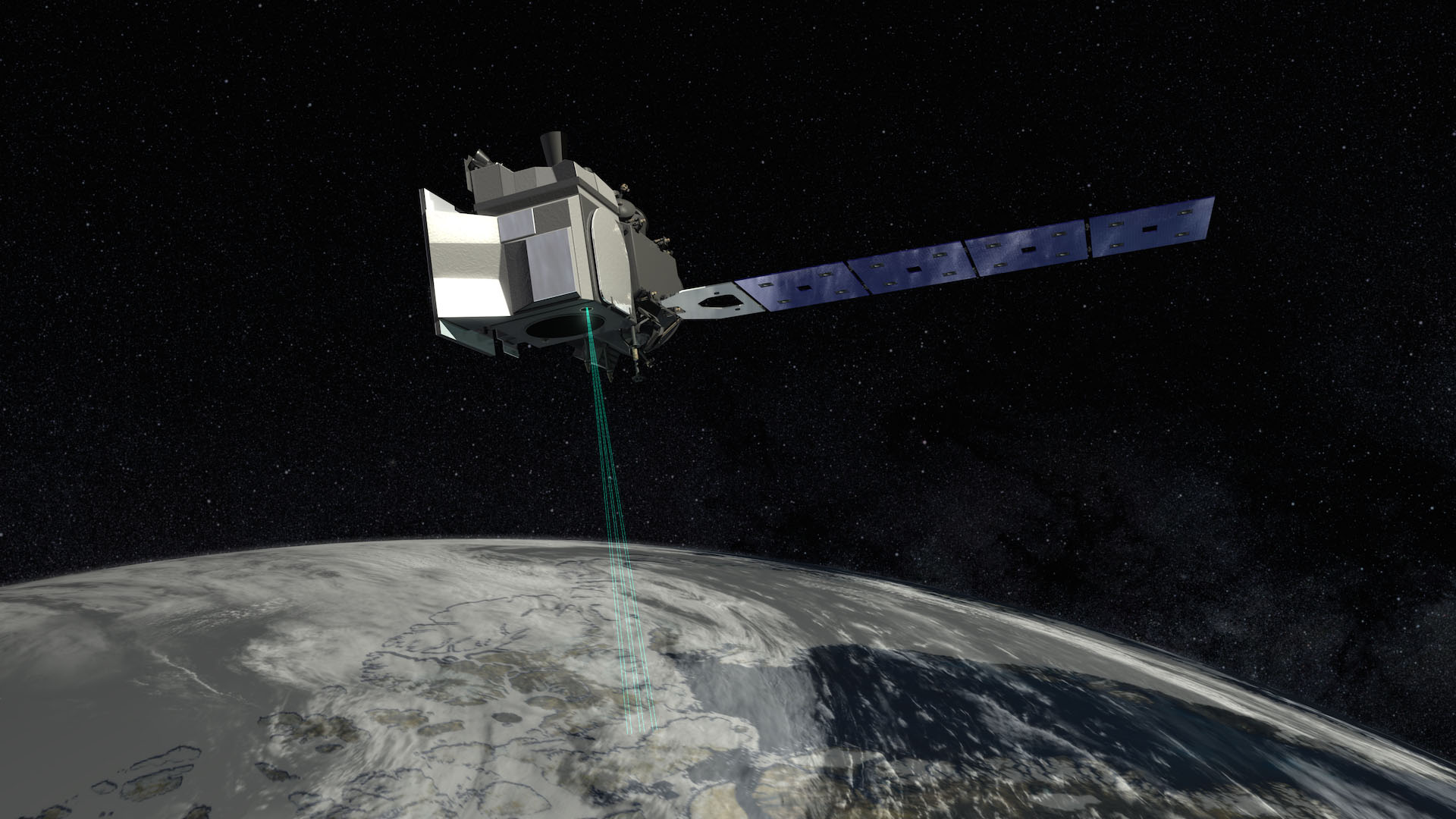

Here's how the new mission works: ICESat-2 will orbit about 300 miles (500 kilometers) above Earth's surface carrying an instrument called the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System (ATLAS). The instrument will constantly emit a laser beam of green light, which will be split into six separate beams as it leaves the satellite. The beams will then bounce off the surface of the ice in a grid pattern. Most of the photons in the laser beams will be lost, but a handful will make their way back to the satellite.

And the satellite can time how long that round-trip took down to the nearest billionth of a second. "ATLAS essentially acts like a stopwatch," Donya Douglas-Bradshaw, instrument manager for the laser, said during the news conference. "The ATLAS laser fires 10,000 pulses a second, with a trillion photons in each shot. Each time the laser fires, it starts the stopwatch." Scientists then convert that time into a distance, calculating the height of the surface at that location. [2 Satellites Will Probe Earth's Massive Ice Sheets (Video)]

While much of ICESat-2's scientific value lies in its laser, its orbit over Earth is also crucially important. The spacecraft will essentially circle from pole to pole, but carefully aligned to retrace its tracks. "The orbit is designed so that after 91 days, which is 1,387 individual orbits of the Earth, it exactly repeats itself," Doug McLennan, ICESat-2 project manager at NASA Goddard, said during the news conference. "This allows the mission to look at the same piece of Earth in each of the four seasons."

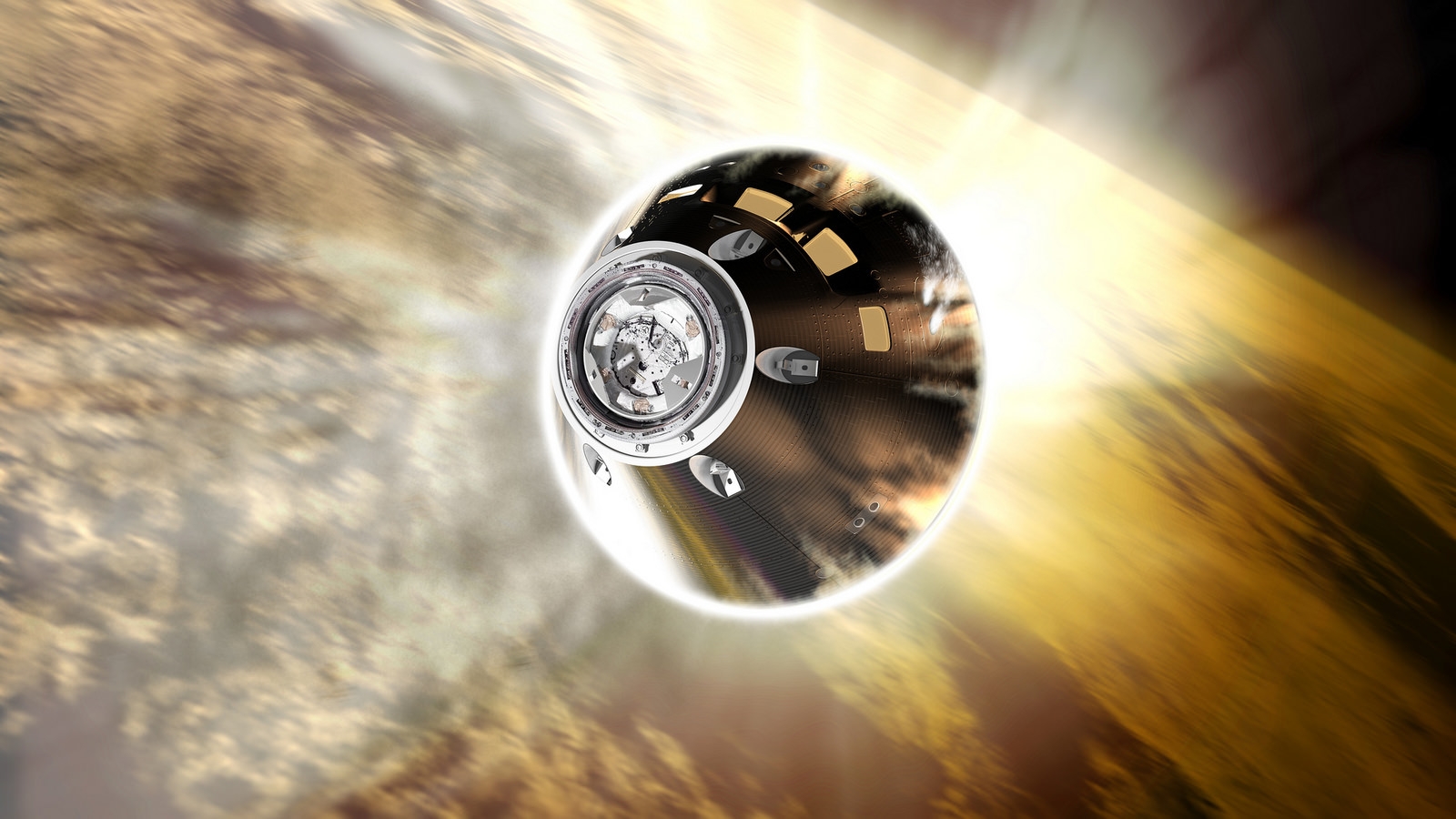

The spacecraft is scheduled to launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California on Sept. 15, during a window that opens at 5:46 a.m. local time (8:46 a.m. EDT, 1246 GMT) and closes at 8:20 a.m. local time (11:20 a.m. EDT, 1520 GMT). ICESat-2's launch will be the last voyage of United Launch Alliance's Delta II rocket, which has seen more than 150 launches over its nearly 30-year career.

After the launch, the team behind ICESat-2 will spend two months commissioning the spacecraft to make sure everything is working properly before it begins gathering science data. The mission is scheduled to last for three years, although the spacecraft will carry enough fuel to potentially stay at work for more than 10 years, should NASA choose to extend its duties.

Once the spacecraft begins its observations, scientists will have access to a wealth of new data about the Earth's ice sheets and how they are changing over time.

"In the half a second that it takes a person to blink, ICESat-2 will collect 5,000 elevation measurements in each of its six beams," Neumann said. "That's every minute of every hour of every day for the next three years."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.