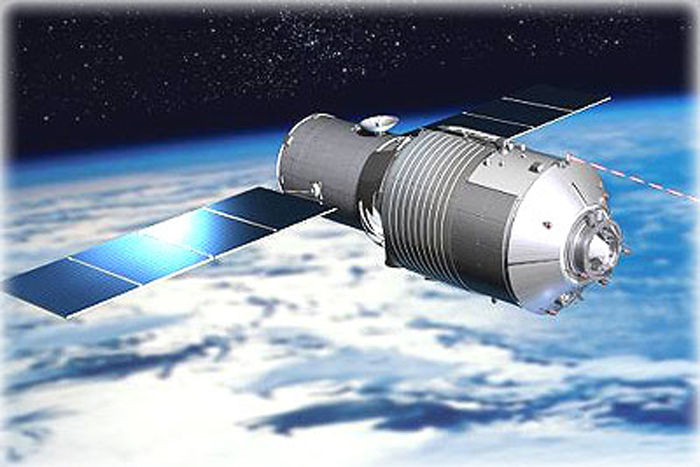

What Will Happen to China's Tiangong-1 As It Falls Through the Atmosphere?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The Chinese space station Tiangong-1 is going to crash to Earth in an uncontrolled re-entry sometime between March 30 and April 2, and it's too soon to say where. But what will happen as the 9.4-ton (8.5 metric ton) satellite falls out of orbit?

First, Tiangong-1 will start to lose altitude. The space station launched in 2011 and has been orbiting Earth at about 217 miles (350 kilometers) above the surface ever since. Objects in low-Earth orbit — below around 1,200 miles (2,000 km) — are still subject to the drag forces of the very top layer of the atmosphere, so they need a periodic boost. This simply consists of docking a powered spacecraft to the bottom of the satellite and turning on the engines for a short period of time, said Roger Launius, a public historian and former associate director at the National Air and Space Museum. The International Space Station used to get these boosts from the space shuttle but now gets them from Soyuz capsules and private resupply missions, Launius told Live Science. [In Photos: A Look at China's Space Station That's Falling to Earth]

Tiangong-1 was put into "sleep" mode in 2013, but Chinese engineers still had some ability to maneuver the spacecraft's position in orbit, keeping it aloft at between 205 miles and 242 miles (330 and 390 km) above the planet, according to the European Space Agency (ESA). However, Chinese authorities announced in 2016 that the space station had stopped communicating data to Earth. Without a way to control the satellite, Tiangong-1's fate was sealed: It would fall to Earth as space debris.

"This is a spacecraft that's not designed to survive re-entry into the atmosphere and come down and land," Launius told Live Science.

Fiery end

As the friction of the upper atmosphere drags on Tiangong-1, it will gradually lose altitude, putting it in contact with even thicker atmosphere and creating more drag, which will pull it down farther and continue to slow its orbit, a process called orbital decay. According to the China Manned Space Engineering Office, Tiangong-1 was orbiting at an average altitude of 131 miles (212 km) as of March 26. That corresponds to a flight velocity of 17,224 mph (27,719 km/h).

At that speed, the friction of the atmosphere generates enormous heat. Spacecraft can withstand this heat if they're covered with heat-shield material, but satellites like Tiangong-1 lack this shielding. In addition to the heat, the space station will start slowing rapidly as it encounters thicker and thicker atmosphere, according to The Aerospace Corporation. The deceleration will introduce loads up to 10 times the acceleration of gravity onto the structure, which begins to break up the spacecraft, peeling off parts and cracking the main body.

Most of the small parts broken off the space station will burn up from the heat generated by the friction, but experts expect that some pieces will survive the inferno of the fall to hit the ground. Close to the ground, where the atmosphere is very dense, the remaining pieces will slow and cool considerably, according to The Aerospace Corporation.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Historical precedent

Small defunct satellites and space debris fall from low-Earth orbit through the atmosphere every month, Launius said. Most of the time, this small stuff burns up, though it can be a danger in actual orbit, where it might collide with manned spacecraft. Bigger stuff has come down before, too, though. The Russian space station Mir re-entered the atmosphere — under control — in March 2001, breaking up over the South Pacific so that any large chunks fell harmlessly into the ocean.

Russia's Salyut 7 space station went into an uncontrolled re-entry in 1991, but its pieces hit the southern Pacific. Salyut 7 weighed about 22 tons (20 metric tons). Much larger was Skylab, NASA's orbiting science lab, which weighed 85 tons (77 metric tons) and went down in July 1979. Skylab's descent was under partial control, as NASA scientists were able to fire its boosters as it entered the atmosphere, aiming the giant chunk of metal at the Indian Ocean. It mostly worked, though some parts did fall over Australia.

"One of them killed a jackrabbit," Launius said.

The unfortunate jackrabbit is one of the few actual casualties of space debris, Launius said. There are no records of anyone being seriously injured or killed by falling space junk, though a woman named Lottie Williams from Tulsa, Oklahoma, got tapped on the shoulder by a soda-can-size piece of metal from a Delta II Rocket in 1997, according to Space Safety Magazine. She was uninjured.

Because no one can predict precisely the moment Tiangong-1 will tumble — and because even a moment's miscalculation of re-entry can translate to hundreds or thousands of miles on the ground — predicting the space station's fall is impossible until about a day before re-entry, according to the ESA. Even then, the estimate will cover many thousands of kilometers. The space agency is posting updates on its website as the day of the fall approaches.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.