Extreme Earth Microbes Pave Way for Discovery of Alien Life

The region beneath Earth's surface may be crawling with diverse organisms, and now researchers reveal the lives of just one group of bizarre beasties: methane-spewing microbes that hide out in the cracks of hot undersea volcanoes.

Called high-temperature methanogens, these microbes rely on the hydrogen and carbon dioxide in their superheated deep-sea vents for growth, excreting waste products like methane.

The possibility of past or present life on other worlds such as Mars, where the rover Curiosity has just set out to investigate whether the environment was ever fit for microbes, will become clearer by figuring out the extreme limits (or minimum requirements) for some organisms on Earth.

"Evidence has built over the past 20 years that there's an incredible amount of biomass in the Earth's subsurface, in the crust and marine sediments, perhaps as much as all the plants and animals on the surface," microbiologist James Holden at the University of Massachusetts said in a statement. "We're interested in the microbes in the deep rock, and the best place to study them is at hydrothermal vents at undersea volcanoes. Warm water flows bring the nutrient and energy sources they need."

One way to figure out what's hidden beneath Earth's crust in extreme environments is to figure out the energy requirements of an organism and then see if various spots meet these thresholds for life. "We're really interested in the equivalent of, 'What is the size of your paycheck and what's the cost of living?'" Holden told LiveScience. "How much energy is available for microorganisms: the paycheck. And what's the lower threshold – they need this much energy to live in this environment." [Gallery: Unique Life at Deep-Sea Vents]

To do this, the researchers collected methanogens from hydrothermal vents and tried growing them (along with commercially bought microbes) on different levels of hydrogen. From these experiments, they found the bare minimum of hydrogen that these microbes needed to survive (they all needed about the same concentrations).

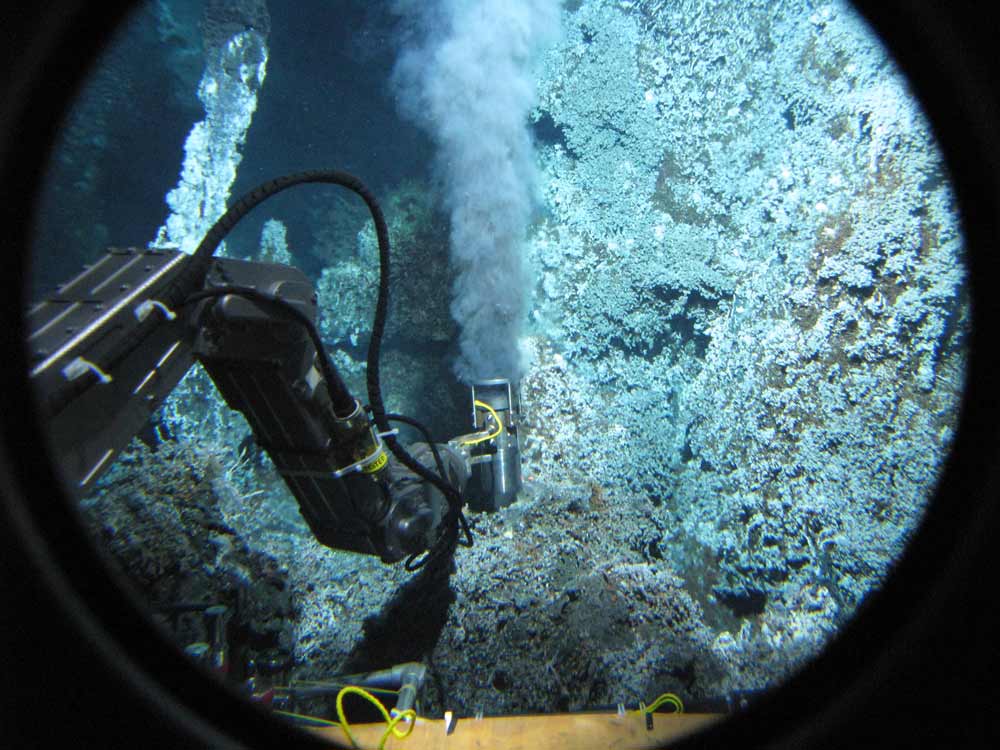

Next, Holden and colleagues sent the deep submersible vehicle Alvin to test out the findings at two spots: the Axial volcano and the Endeavor segment, both observatory sites along an undersea mountain range well off the coast of Washington state and Oregon and about 1 to 1.5 miles (1.6 to 2.4 kilometers) below the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Alvin collected samples from the sites' black smokers, where mineral-rich, superheated water ? up to 662 degrees Fahrenheit (350 degrees Celsius) ? spews out of Earth's crust through cracks in the seafloor, and it also took samples from surrounding, lower-temperature waters.

The hydrogen limits found in the lab held up in the field. At the Axial volcano site, where the scientists found hydrogen levels above the lab-determined threshold, they also found evidence of methanogenic microbes; at Endeavour, hydrogen levels were below the threshold, with evidence of methane-producers largely absent. However, they found heat-loving methanogens could survive by feeding on hydrogen produced by other extreme organisms living near the vent.

In addition to painting a more comprehensive picture of Earth's biodiversity today, the findings may reveal what life was like on early Earth, "where we think [life] was independent of sun and oxygen," Holden said.

His research also can be used beyond Earth, he says; the astrobiology community uses this sort of data to rule in or out the possibility of past extraterrestrial life on, say, Mars or the Jupiter moon Europa.

"How much energy is available and what's the 'cost of living' for these organisms, and could Mars have had enough energy to support this kind of life?" Holden said during a telephone interview.

The research, detailed this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was supported by the National Science Foundation, NASA Astrobiology Institute and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.

This story was provided by LiveScience, a sister site to SPACE.com. Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.