Ancient Egyptian Calendar Reveals Earliest Record of 'Demon Star'

Ancient Egyptians may have chronicled the flickering of a star known as "the Demon," perhaps the earliest known record of a variable star, astronomers suggest.

The ancient Egyptians wrote calendars that marked lucky and unlucky days. These predictions were based on astronomical and mythological events thought of as influential for everyday life. The best preserved of these calendars is the Cairo Calendar, a papyrus document dating between 1163 and 1271 B.C. The entry for each day is prefaced by three hieroglyphics that indicate either good or bad luck, with the characters often derived from events of mythology.

Astronomers at the University of Helsinki in Finland had previously discovered that some of the fortunate days recurred in a pattern, every 29.6 days. This almost exactly matches the length of the lunar cycle — the time between two full moons. New moons may have been associated with bad luck.

Dimming demon star

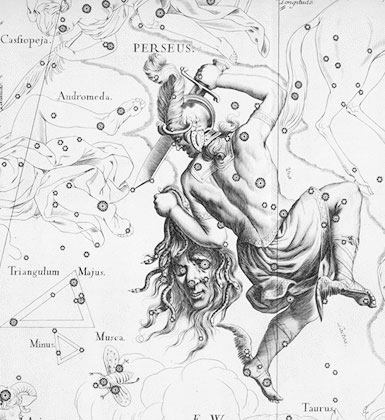

The scientists also detected another pattern in the calendar, one that occurred every 2.85 days. Now the researchers suggest this approximately matches regular dimming of Algol, "the Demon Star," which lies approximately 93 light-years away in the constellation Perseus as one of the eyes of Medusa's head. Its name comes from the Arabic phrase, ra's al-ghul, which means "the demon's head."

Algol is the brightest known example of an eclipsing binary system — the large bright member of the system, Beta Persei A, regularly gets eclipsed by the dimmer Beta Persei B. From our point of view, Algol dims by more than a factor of three for 10 hours at a time, dwindling easily seen with the naked eye.

"It seems that the first observation of a variable star was made 3,000 years earlier than was previously thought," said researcher Lauri Jetsu, an astronomer at the University of Helsinki.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Cairo Calendar describes how Wedjat, the Eye of Horus, regularly transformed from peaceful to raging, with good or bad influences on life. Horus was the patron god of kings in ancient Egypt. [Gallery: Sun Gods and Goddesses]

"The eclipse seems to be linked with the lucky days, because it represents the pacification of the Eye of Horus," researcher Sebastian Porceddu, an astronomer and Egyptologist at the University of Helsinki, told LiveScience. "A bright Eye of Horus meant it is raging and a threat to mankind."

Pinch of salt?

In modern times, Algol actually dims every 2.867 days. The researchers suggest this discrepancy of 0.017 days — about 25 minutes — between ancient Egyptian and modern values for Algol's dimming may be due to changes Algol may have undergone in the past three millennia. Matter is apparently flowing from the dimmer member of this eclipsing binary to the brighter star, altering their orbit so that eclipses now take longer than they once did. If correct, this ancient Egyptian data could shed light on eclipsing binaries and the details of how such mass transfer might affect their orbits.

"I believe that from now on, Egyptologists will be keeping an eye on possible references to Algol elsewhere," Porceddu said.

Other scientists are intrigued by the idea, but remain skeptical.

"I think it's an interesting idea — just how convincing it is is another issue," astrophysicist Peter Eggleton at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, who did not take part in this research, said in an interview.

This pattern "does seem very plausibly attributed to Algol, and the suggestion that it has slowed down by a small amount over 3,000 years is not unreasonable," Eggleton said. "But you do have to take the idea with a pinch of salt — it's obviously difficult to pin down what people were really thinking 3,000 years ago."

The scientists submitted their findings to the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

This article was provided by LiveScience.com, a sister site of SPACE.com. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescienceand on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us