Space-Time Around Black Holes Visualized

For the first time, physicists have visualized what goes on during the collision of two black holes, providing insight into what one researcher calls the "stormy behavior" of space and time during such a merger.

The findings could help researchers interpret gravitational signals from space to reconstruct the cosmic events that created them, said study researcher Kip Thorne, a theoretical physicist at the California Institute of Technology. The study also opens up a new way to understand black holes, gravity and cosmology.

"It's as though we had only seen the surface of the ocean on a calm day," Thorne told LiveScience. "We'd never seen the ocean in a storm, we'd never seen a breaking wave, we'd never seen water spouts … We have never before understood how warped space and time behave in a storm."

Here's how black holes and space-time are linked: The theory of general relativity, proposed by Albert Einstein in 1915, describes how gravity affects very massive, huge things such as black holes and the universe itself. According to this theory, gravity actually warps the fabric of space-time in such a way that massive objects bend the universe (think a Sumo wrestler on a soft mat) so that objects can't help but fall toward them. Even time can be bent by gravity, the theory goes.

Vortex and tendex

In other words, researchers had a good handle on the forces created by a quietly spinning black hole. They were also able to simulate the results of black hole collisions to see what type of gravitational waves the collisions create. "What we were not able to do is go down and look at the merger itself," Thorne said. [See a video of the black hole collisions]

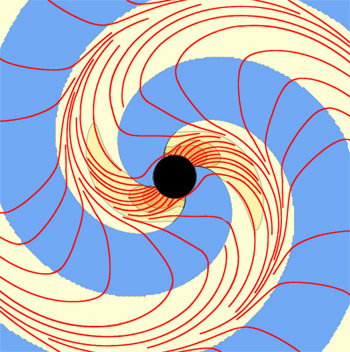

To visualize a black hole merger, the researchers used two concepts, one old and one new: vortex lines and tendex lines. These lines are the equivalent of the lines drawn to represent magnetic fields, said study author Robert Owen, a postdoctoral researcher in astronomy at Cornell University.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Vortex lines represent a twisting force in space-time. If you were to fall into a vortex line, your body would be wrung like a wet dish towel, Owen said. Tendex lines, which are a new concept, represent a stretching or squeezing force. [Visualization of vortex lines]

"Tendex is actually a word that we had to invent because it didn't exist before this," Owen said.

Using supercomputers, the researchers created simulations of the vortex and tendex lines that would be created when black holes merge. The patterns differ depending on how the merger happens, Thorne said. For example, a head-on collision of two black holes ejects doughnut-shaped vortexes from the merger. Two black holes spiraling into each other create a very different arrangement.[ Gallery: Black Holes of the Universe]

"This is where we see vortexes sticking out of the merged black hole that swing around the merged black hole like spiral arms of the galaxy or like water spraying out of a rotating sprinkler head," Thorne said.

In another simulation of spinning black holes orbiting into each other, the vortexes diffused into one another, Thorne said.

Tracing the source

The researchers are working on three follow-up studies to explore the details of the dynamics involved, Owen said. He said the research team expects that tendexes and vortexes will be used to investigate lots of situations where gravitational forces are very strong, including just after the Big Bang that may have created the universe about 13.7 billion years ago.

Whether any valuable insights will come out of the new visualization method has yet to be seen, University of Texas, Brownsville and Southmost Texas College physicist Richard Price told LiveScience. But the method has more potential than any other method he knows of, Price said.

"My initial impression [upon hearing about the research] was, 'Yeah. This could work,'" said Price, who was not involved in the study.

"You can't calculate everything; you've got to know where to look," Price added. "And therefore, you need to have the ability to visualize."

The results may also help researchers understand the findings of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, an instrument that detects gravitational waves from space. Before, researchers knew enough about black hole collisions to figure out what sorts of waves LIGO should be looking for, Thorne said. Now, scientists can start interpreting those waves when they come in.

"We want to be able to look at the shapes of the waves and be able to go back and say what was happening to produce the waves," Thorne said.

This story was provided by LiveScience, a sister site to SPACE.com.You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.