Giant Jupiter Shines Bright

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Planets are very much in the fore these days, especiallywith three of them now putting on a show as prominent evening luminaries.

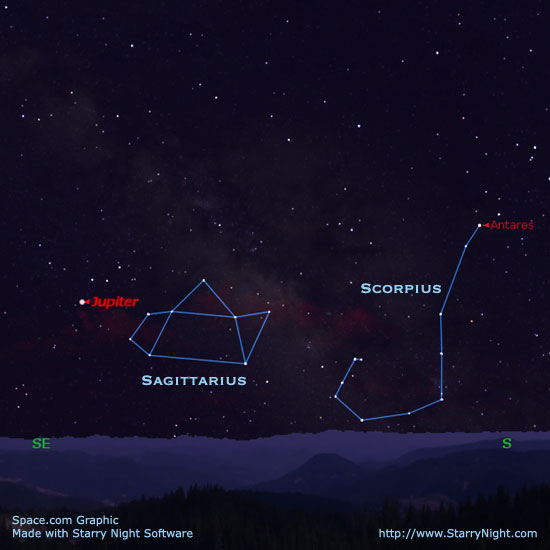

Over in the west-northwest sky at dusk, Mars and Saturn remain alovely sight in close proximity to the bright bluish star, Regulus in Leo. Meanwhile,emerging into view low in the southeast you?ll note a very bright silvery"star." That star however, is the planet identified with the supremesky-god: Jupiter.

The heavenly ballet continuously being performed by these"wandering stars" has played a crucial role in the celestial lore ofall peoples. It is not surprising that they were regarded as deities. The fivenaked-eye planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn) have been knownsince antiquity, and it is also interesting that the members of this quintethave all been examined closely by space probes.

A star is (almost) born

Of course, before the advent of the telescope, all peoplesregarded planets as a special category of star. And in a strange sense, Jupiter might even be referred to as astillborn star, for it has the makings (mostly hydrogen), if not the mass of astellar body.

With a diameter of 88,900 miles (143,000 km), Jupiter is thelargest planet in our solar system, a colossal ball of hydrogen and heliumwithout a solid surface. It has a rocky core encased in a thick mantle ofmetallic hydrogen enveloped in a massive atmospheric cloak of multi-coloredclouds of ammonium hydrosulphide.

Its relative smallness, however, prevents the initiation ofthe nuclear processes that could have turned it into a full-fledged star. Hadthis been the case, we would have the distinction of living within a binarystar system.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

At its best

At 4 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time on July 9, Jupiter willarrive at that point in the sky directly opposite to the Sun, called "opposition."It will then be visible all night long at its brightest and (in telescopes)biggest. It rises in the southeast at sunset and burns near the teapot figureof Sagittarius, not far from the south end of the summer Milky Way.

If the planets' paths around the Sun were true circles, themoment of opposition would coincide with our closest approach to Jupiter, 387million miles (623 million km). That actually will take place 27 hours later.

Opposition occurs when the Earth, moving faster in its orbitthan Jupiter, overtakes it. From then on, we?ll leave Jupiter behind. Jupiteris also currently moving toward the Sun in its own elliptical path, while theEarth is arriving at its farthest point from the Sun.

Jupiter will reach its closest point to the Sun, 368 millionmiles (592 million km), at its perihelion point on September 20, 2010. Earth onthe other hand, always attains its maximum distance from the Sun (aphelion) inearly July. At 3 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time on July 4, it will be 94.5 millionmiles (152.1 million km) away.

Check it out!

Once it climbs a reasonable distance above the southeasthorizon — say two to three hours after sundown — take a good look at Jupiter througha telescope.

Along with a restless atmosphere it also boasts a retinue ofbright satellites. While steadily held binoculars show Jupiter as a tiny disc,a medium-size telescope reveals numerous dark belts, light zones and a wealthof festoons, garlands, ovals and other features extending here and there, aswell as Jupiter's most famous feature, its Great Red Spot.

And the smallest telescope — even steadily held 7-powerbinoculars — will reveal Jupiter?s four largest satellites, each of which isequal to or larger than our Moon. The moons are a telescopic treasure. The four— Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto — popularly known as the "Galileansatellites," run a merry race with each other around the planet. Typicallyat least two or three are visible at any given moment. They can be followed forhours as they speed in front of Jupiter, throwing their shadows on the planet,vanish behind its giant disc, or plunge into invisibility within its dark shadow.

For instance: on the night of July 7, at 11:43 p.m. Eastern(8:43 p.m. Pacific) Time, Io will emerge into view, having crossed directly infront of Jupiter. For the rest of the night all four moons will be visible onone side of Jupiter. Pay especially close attention to Europa and Ganymede forthey will be drawing closer to each other. At 2:40 a.m. Eastern Time (on July8), they will be at their closest, separated by only 8 arc-seconds. That's lessthan one-sixth of the apparent diameter of Jupiter!

And during the night of July 29-30, it will appear as ifJupiter has gained a fifth satellite. That will be because it will be passingvery closely north of HIP93649, a faint background star in Sagittarius. Attheir closest, they'll appear just 2 arc-minutes apart or about 2-and-a-halftimes Jupiter's apparent diameter.

- Online Sky Maps and More

- Sky Calendar & Moon Phases

- Astrophotography 101

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and otherpublications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.