Star Devours Hottest Known Alien Planet

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

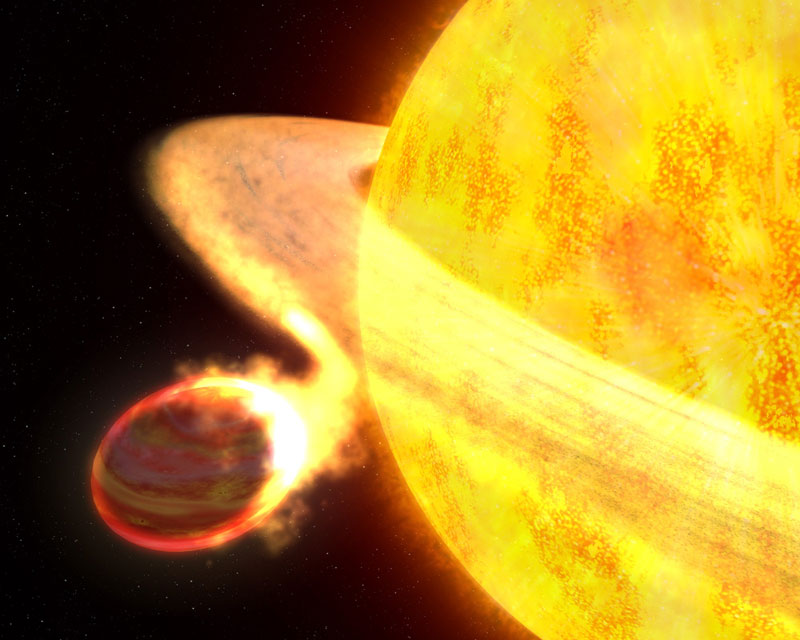

The hottest known planet in our galaxy is being stretched into the shape of a football and rapidly consumed by its parent star, new observations from the Hubble Space Telescope show.

The extrasolar planet on the cosmic menu, called WASP-12b, may only have another 10 million years left before it is completely devoured, Hubble scientists announced Thursday.

WASP-12b is so close to its sun-like star that it is superheated to nearly 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit and stretched into an elongated shape by enormous tidal forces.

Because of those phenomenal forces, the planet's atmosphere has ballooned to nearly three times Jupiter's radius and is pouring material onto its parent star. WASP-12b is 40 percent more massive than Jupiter.

This effect of matter exchange between two stellar objects is commonly seen in close binary star systems, but this is the first time it has been seen so clearly for a planet. The system was observed with the new Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) instrument on Hubble.

"We see a huge cloud of material around the planet which is escaping and will be captured by the star. We have identified chemical elements never before seen on planets outside our own solar system," said team leader Carole Haswell of The Open University in the United Kingdom.

The distortion of the planet by the star's gravity was first predicted in a paper published in February in the journal Nature by Shu-lin Li of Peking University in Beijing. That work predicted that the gravitational tidal forces working on the planet would make its interior so hot that it greatly expands the planet's outer atmosphere.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Now Hubble has confirmed this prediction.

The planet's parent star, WASP-12, is a yellow dwarf star located approximately 600 light-years away in the winter constellation Auriga. The exoplanet it is slowly destroying was discovered by the United Kingdom's Wide Area Search for Planets (WASP) in 2008.

The unprecedented ultraviolet (UV) sensitivity of COS enabled measurements of the dimming of the parent star's light as the planet passed in front of the star.

These UV spectral observations showed that absorption lines from aluminum, tin, manganese, among other elements, became more pronounced as the planet transited the star, meaning that these elements exist in the planet's atmosphere as well as in the star. The fact the COS could detect these features on a planet offers strong evidence that the planet's atmosphere is greatly extended because it is so hot, researchers said.

The new observations of WASP-12b are detailed in the May 10 issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

- Gallery - The Strangest Alien Planets

- Top 10 Extreme Planet Facts

- Out There: A Strange Zoo of Other Worlds

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.