Ancient Huts May Reveal Clues to Earth's Magnetic Pole Reversals

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The fiery demise of ancient huts in southern Africa 1,000 years ago left clues to understanding a bizarre weak spot in the Earth's magnetic field — and the role it plays in the magnetic poles' periodic reversals.

Patches of ground where huts were burned down in southern Africa contain a key mineral that recorded the magnetic field at the time of each ritual burning. Those mineral records teach researchers more about a weird, weak patch of Earth's magnetic field called the South Atlantic Anomaly and point the way toward a possible mechanism for sudden reversals of the field.

"It has long been thought reversals start at random locations, but our study suggests this may not be the case," John Tarduno, a geophysicist from the University of Rochester in New York and lead author of the paper, said in a statement. [How Earth's Magnetic Field Shielded Us from 2014 Solar Storm]

Tarduno told Space.com in an interview that data from the huts suggest that the strange weak patch "forms, and it decays away, and it forms, and it decays away; eventually, one might form and get really large, and then we might actually have a geomagnetic reversal."

Something strange in the South Atlantic

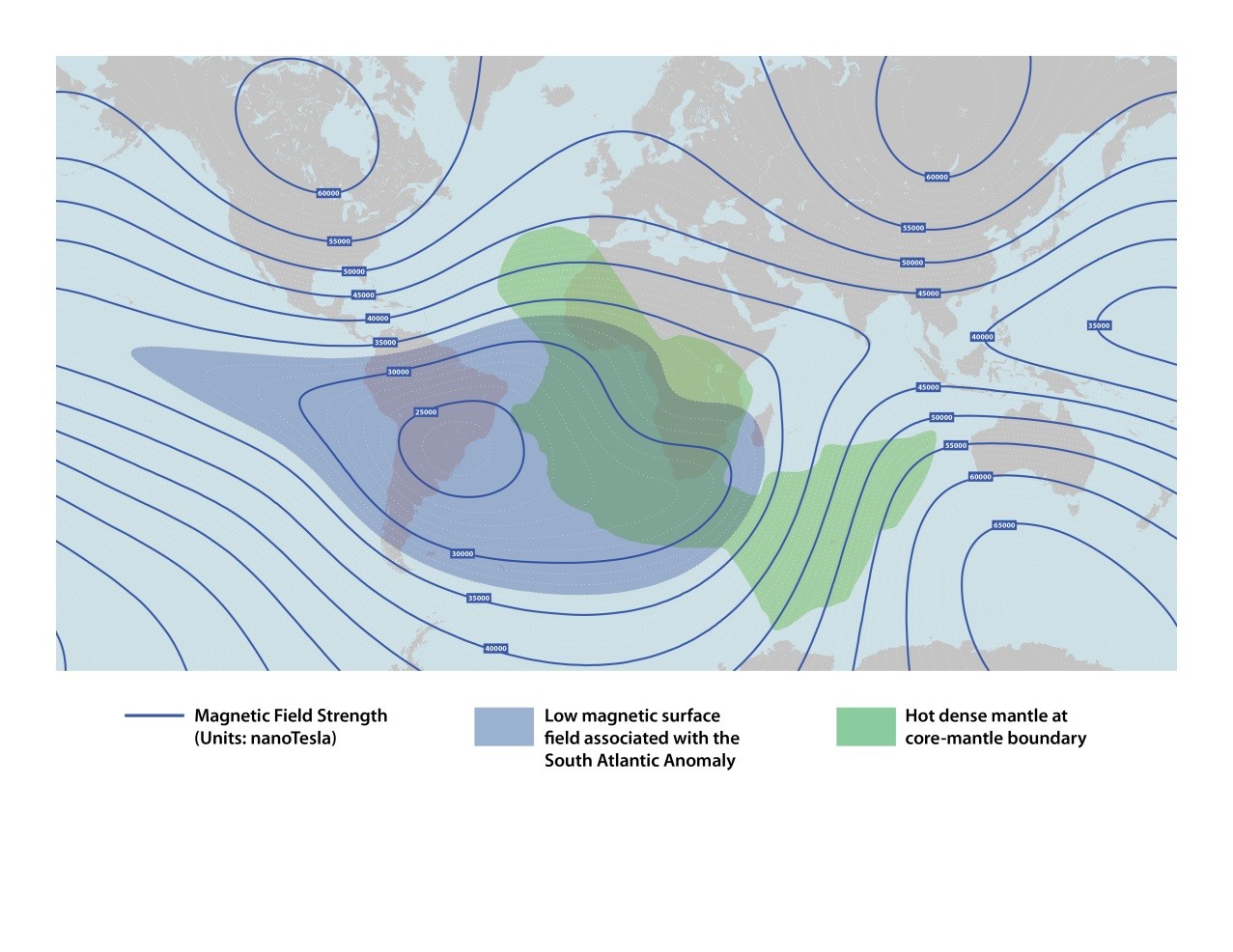

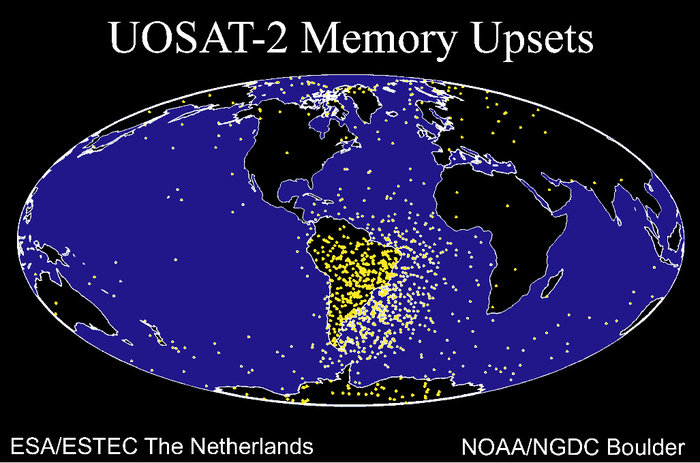

The South Atlantic Anomaly is a dent in Earth's shield against cosmic radiation, 124 miles above the ground (200 kilometers). It may be the most dangerous place in the Earth's sphere for satellites and spacecraft to traverse, because anything electronic traveling through it is vulnerable to strong radiation from space and tends to malfunction.

Even the Hubble Space Telescope takes no measurements when passing over the anomaly. It's an area where, instead of pointing outward, part of the Earth's magnetic field actually ushers energetic particles down instead of repelling them, weakening the overall field in the area. And it has been growing.

"Some have postulated that the Earth's magnetic field is leaking out the wrong way at that particular spot," Rory Cottrell, a geologist also at the University of Rochester and co-author of the new paper, told Space.com. "One theory is that changes in the South Atlantic Anomaly could be responsible for the decrease in the overall magnetic field that we're seeing, because these patches are growing or changing over time."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Many researchers have speculated that this kind of anomaly is temporary, caused by changes of flow within the Earth's outer, iron core, which generates the planet's magnetic field. Such anomalies, in weakening the magnetic field, may bring the Earth closer to a magnetic reversal — when the magnetic north and south poles on Earth switch places, rearranging the magnetic field over the course of 1,000 to 10,000 years (although it can happen faster). The process generally happens every 200,000 to 300,000 years, after the magnetic field weakens enough, but the last magnetic-field reversal occurred 780,000 years ago.

The new data from the African burnings suggests that the South Atlantic Anomaly was up to its same field-weakening tricks over 1,000 years ago; if it's caused by something permanent near the Earth's core, it might play an important role in the Earth's magnetic-pole reversals.

Burn it all down

Modern magnetic records only stretch back for the past 150 years or so, and within that time frame, researchers have seen the Earth's magnetic field rapidly decrease in intensity. But the researchers used the Iron Age remnants of African villages to extend their view even further back, from A.D. 1,000 to A.D. 1,850 — and the record reveals that the South Atlantic Anomaly was going strong at that time, too. [Earth Quiz: Do You Really Know Your Planet?]

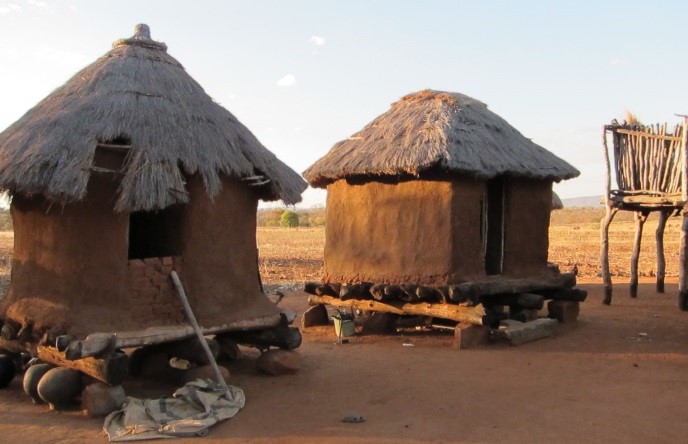

Throughout that time, the inhabitants of ancient African villages would burn down the huts and grain bins in their villages on a regular basis, giving scientists key, consistent data throughout that time period.

"They had this ritualistic burning of villages," Tarduno told Space.com. "Particularly in times of drought, the conclusion would be that there might have been some offence in the village, so the solution was to have a burning down of the village." The process was intended to cleanse the village, their collaborator archaeologist Thomas Huffman, from Witwatersrand University in South Africa, said in the statement.

At the very least, it cleansed the ground: The burning villages would reach temperatures of over 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius), which would melt the magnetic compounds like magnetite in the clay floors. The magnetite would become remagnetized by the Earth's magnetic field at the precise instant it cooled, ready to be analyzed centuries later.

"The hut floors are actually very good magnetic recorders," Tarduno said. "Sort of like minimagnetic observatories back in time."

Researchers had obtained very little historical data in the southern hemisphere, and none in southern Africa before these findings. The new baked-clay records revealed an eerily familiar picture of the Earth's magnetic field: Just like today, the Earth's magnetic field at the time was steadily weakening, with a focus on that same South Atlantic Anomaly. The effect did not appear to be continuous, but rather seemed to be a recurring event in that part of the globe, whose weakening power comes and goes over time.

Digging deeper

To Tarduno's group, that consistently recurring spot of weakening suggests that a permanent feature deep below the Earth's surface may be generating the South Atlantic Anomaly and might therefore play a role in the reversal of the Earth's magnetic field.

That feature is a section of particularly hot and dense mantle rock just above the Earth's outer core. The section is 1,860 miles (3,000 km) below southern Africa and the Atlantic, and it's about as wide as the distance between New York and Paris. Scientists call it the Large Low Shear Velocity Province, and Tarduno's group suspects that its sharp boundaries might disrupt the flow of iron within the Earth's core, creating a strange, field-weakening eddy that could lead to reversals time and time again.

The researchers' model is only one of many theories about magnetic pole reversal, and they're focusing on refining the mathematics and gathering more, even earlier data from southern Africa to further track the weak spot.

"No one knows what causes reversals, and there is no agreement on whether we can ever even find convincing evidence to forecast a reversal," Ron Merrill, a geophysicist from the University of Washington, who was not involved in the study, told Space.com in an email.

While the new magnetic field records in Africa are useful in their own right, he wrote, it will take much more testing and theory to make a solid connection between the feature near the Earth's core and the magnetic field's weakening and reversal (and the long-lasting nature of the South Atlantic Anomaly).

The new research can't predict the next magnetic field reversal, but finding a connection between the ancient irregularity near the Earth's core and a weakening magnetic field would be one more step toward deciphering the incredibly complex magnetic system that protects humanity from the harsh radiation of space.

This research is detailed in the July 28 edition of the journal Nature Communications.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.