Leaks Found in Earth's Protective Magnetic Field

Scientistshave found two large leaks in Earth?s magnetosphere, the region around ourplanet that shields us from severe solar storms.

The leaksare defying many of scientists' previous ideas on how the interaction between Earth'smagnetosphere and solar wind occurs: The leaks are in an unexpectedlocation, let in solar particles in faster than expected and the wholeinteraction works in a manner that is completely the opposite of whatscientists had thought.

Thefindings have implications for how solarstorms affect the our planet. Serious storms, which involved chargedparticles spewing from the sun, can disable satellites and even disrupt powergrids on Earth.

The newobservations "overturn the way that we understand how the sun's magneticfield interacts with the Earth's magnetic field," said David Sibeck of NASA'sGoddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., during a press conference todayat the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

The bottomline: When the next peak of solar activity comes, in about 4 years, electricalsystems on Earth and satellites in space may be more vulnerable.

How itworks

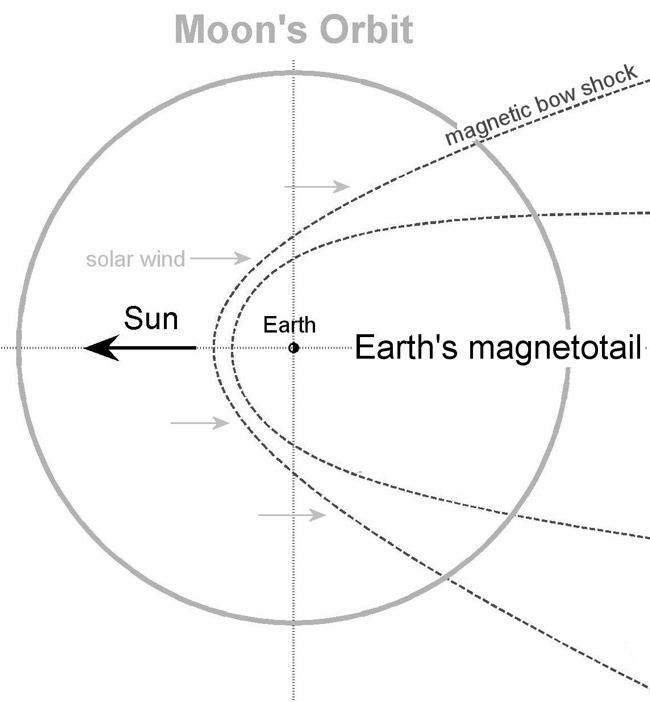

Earth's magneticfield carves out a cavity in the sun's onrushing field. The Earth'smagnetosphere is thus "buffeted like a wind sock in gale force winds,fluttering back and forth in the" solar wind, Sibeck explained.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Both thesun's magnetic field and the Earth's magnetic field can be oriented northwardor southward (Earth's magnetic field is often described as a giant bar magnetin space). The sun's magnetic field shifts its orientation frequently,sometimes becoming aligned with the Earth, sometime becoming anti-aligned.

Scientistshad thought that more solar particles entered Earth's magnetosphere when thesun's field was oriented southward (anti-aligned to the Earth's), but theopposite turned out to be the case, the new research shows.

The workwas sponsored by NASA and the National Science Foundation and based onobservations by NASA's THEMIS(Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms)satellite.

How manyand where

Essentially,the Earth's magnetic shield is at its strongest when scientists had thought itwould be at its weakest.

When thefields aren't aligned, "the shield is up and very few particles come in,"said physicist Jimmy Raeder of the University of New Hampshire in Durham.

Conversely,when the fields are aligned, it creates "a huge breach, and there's lotsand lots of particles coming in," Raeder added, at the news conference.

As itorbited Earth, THEMIS's five spacecraft were able to estimate the thickness ofthe band of solarparticles coming when the fields were aligned ? it turned out to be about20 times the number that got in when the fields were anti-aligned.

THEMIS wasable to make these measurements as it moved through the band, with twospacecraft on different borders of the band; the band turned out to be oneEarth radius thick, or about 4,000 miles (6,437 kilometers). Measurements ofthe thickness taken later showed that the band was also rapidly growing.

"Sothis really changes our understanding of solar wind-magnetosphere coupling,"said physicist Marit Oieroset of the University of California, Berkeley, also at the press conference.

And whilethe interaction of anti-aligned particles occurs at Earth's equator, those ofaligned particles occur at higher latitudes both north and south of theequator. The interaction is "appending blobs of plasma onto the Earth'smagnetic field," which is an easy way to get the solar particles in, said Sibeck,a THEMIS project scientist.

Nextsolar cycle

Thisfinding not only has implications for scientists' understanding of theinteraction between the sun and Earth's magnetosphere, but for predicting theeffects to Earth during the next peak in the solar cycle.

The Sunoperates on an 11-year cycle, alternating between active and quiet periods. Weare currently in a quiet period, with few sunspots on the sun's surface andfewer solar flares, though the nextcycle of activity has begun. It is expected to peak around 2012, bringinglots of sunspots, flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs). CMEs can interactwith the Earth's magnetosphere, causing problems for satellites,communications, and power grids.

Thisupcoming active period now looks like it will be more intense than the previousone, which peaked around 2006, some scientists think. The reason is the changesin the sun's alignment.

During thelast peak, solar fields hitting the Earth were first anti-aligned then aligned.Anti-aligned fields can energize particles, but in this case, the energy camebefore the particles themselves, which doesn't create much of a fuss in termsof geomagnetic storms and disruptions.

But thenext cycle will see aligned, then anti-aligned fields, in theory amplifying theeffects of the storms as they hit.

Raederlikens the difference to igniting a gas stove one of two ways: In the firstway, the gas is turned on and the stove is lit and you get a flame. In theother way, you let the gas run for awhile, so that when you add the gas you geta much bigger boom.

"Itshould be that we're in for a tough time in the next 11 years," Sibecksaid.

- Video ? Danger: Solar Storm!

- Top 10: The Wildest Weather in the Galaxy

- Images: Sun Storms

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.