A Cosmic Storm: When Galaxy Clusters Collide

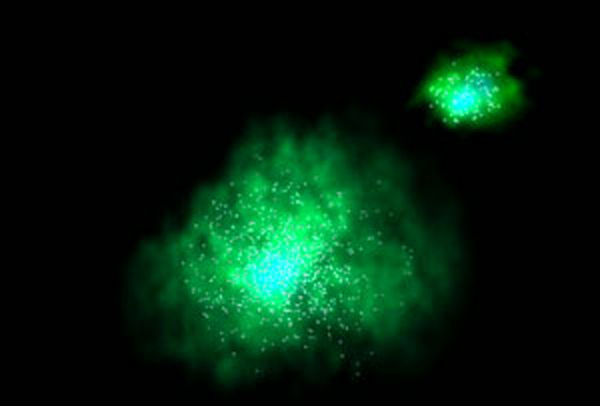

Astronomers have found what they are calling the perfect cosmic storm, a galaxy cluster pile-up so powerful its energy output is second only to the Big Bang.

The cluster collision is the most powerful ever recorded and a fresh glimpse of the cluster merging process, where great swarms of galaxies smash into one another to form a single galactic structure.

"We are now able to see things in nature of what was previously only available in computer simulation," said astronomer Patrick Henry, of the University of Hawaii, during a Sept. 23 teleconference with reporters.

Henry led an international team of astronomers that used a space-based X-ray observatory to peer at an object known as Abell 754 - the product of the collision between two smaller galaxy clusters about 300 million years ago. Finding observable evidence of such collisions bolsters theories that the universe formed in a "bottom up" hierarchical structure where stars and galaxies collected and merged together to form larger galaxies and galaxy clusters.

Galaxy clusters are the largest structures in the universe to be bound by gravity, some containing the mass of up to 10,000 times that of our own Milky Way, researchers said. The Milky Way, is part of a galactic club dubbed the Local Group, which could slam into the Virgo Cluster in a few billion years, though the expansion of the universe may prevent it, they added.

A tale of two clusters

Based on their observations, Henry and his colleagues were able to backtrack the Abell 754 collision to its two constituent galaxy clusters, with one smaller than the other.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The smaller cluster most likely contained about 300 galaxies, while its larger neighbor about 1,000 galaxies, researchers said. But when the two clusters collided with one another, they formed a still unsettled super cluster about 1 million light-years across that should take another billion years to settle down completely, researchers said. One light-year is the distance a beam of light travels in a year, about 6 trillion miles (10 trillion kilometers).

"This cluster is closer us than some of the others," said August Evrard, a University of Michigan astronomy and physics professor, of Abell 754. "Which makes it brighter and easier to study."

In the new study, researchers used the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton X-ray observatory to study the cluster. In addition to plotting the collision, researchers took detailed pressure, temperature and density readings to generate a "weather map" of the two galaxy clusters and make a forecast for the settling period.

"The weather in this cluster is a cosmic version of [Hurricane] Ivan," said Evrard said. "These big storms are themselves rare events."

Abell 754 sits about 800 million light-years away in the constellation Hydra in the southern sky. The research will appear in an upcoming issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

On the right track

Researchers said the Abell 754 observations match closely with those predicted by computer models and are a sign that astronomers are on the right track with theories of galactic evolution and the structure of the universe.

NASA researcher Richard Mushotzky, U.S. project scientist for the XMM-Newton observatory, told reporters that the research also adds to the understanding of dark matter and dark energy, two invisible phenomena that can determine the rate of merging galactic clusters.

"In some ways, galaxy clusters are the universe in a box," Mushotzky said. "If we can understand them with some detail, we can apply those findings to the universe as a whole."

Tariq is the award-winning Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001. He covers human spaceflight, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He's a recipient of the 2022 Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting and the 2025 Space Pioneer Award from the National Space Society. He is an Eagle Scout and Space Camp alum with journalism degrees from the USC and NYU. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.