Seeds of Monster Black Holes Were Surprisingly Big

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The gigantic black holes that lurk at the hearts of galaxies were apparently born big.

The central black holes in dwarf galaxies — the "seeds" that grow into the monsters at the core of the Milky Way and other large galaxies — are probably surprisingly weighty, containing 1,000 to 10,000 times the mass of our sun, a new study reports.

The finding goes against one popular theory of supermassive black hole evolution, suggesting that galaxy mergers aren't necessary to create these behemoths, which can harbor billions of times more mass than the sun. [The Strangest Black Holes in the Universe]

"We still don't know how the monstrous black holes that reside in galaxy centers formed," lead author Shobita Satyapal, of George Mason University in Virginia, said in a statement. "But finding big black holes in tiny galaxies shows us that big black holes must somehow have been created in the early universe, before galaxies collided with other galaxies."

It's also possible that supermassive black holes grow primarily by gobbling up gas and dust, getting bigger relatively sedately along with their host galaxies, researchers said.

Satyapal and her colleagues analyzed observations of dwarf galaxies made by NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer spacecraft, or WISE.

Dwarf galaxies have changed relatively little over time, and they resemble the types of galaxies that existed when the universe was young. So they're a good place to look for nascent supermassive black holes, researchers said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

WISE's all-sky survey picked out hundreds of dwarf galaxies, which appear to sport strikingly large black holes.

"Our findings suggest the original seeds of supermassive black holes are quite massive themselves," Satyapal said.

While the results are intriguing, follow-up study will be necessary to fully flesh them out, outside researchers said.

"Though it will take more research to confirm whether the dwarf galaxies are indeed dominated by actively feeding black holes, this is exactly what WISE was designed to do: find interesting objects that stand out from the pack," astronomer Daniel Stern, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. Stern was not part of the study team.

WISE launched to Earth orbit in December 2009 on a 10-month mission to scan the entire sky in infrared light. It was shut down in February 2011, then reactivated in September 2013 with a new mission and a new name. Now called NEOWISE, the spacecraft is hunting for potentially dangerous asteroids, some of which could be promising targets for human exploration.

The new study was published in the March issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

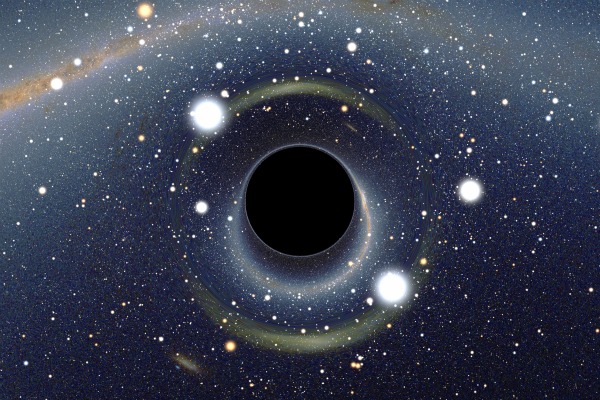

![Black holes are strange regions where gravity is strong enough to bend light, warp space and distort time. [See how black holes work in this SPACE.com infographic.]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/8GbuLi8DVtx8HoZeSyndT7.jpg)