What We Don't Know About Asteroids

When the Japanese space probe Hayabusa returns to Earth Sunday, it may carry the first samples ever recovered by a mission to an asteroid. This space dust could raise as many questions as it answers, researchers suggest, joining the host of mysteries currently surrounding these cousins to our planets.

Where do meteorites emerge from?

While a number of meteorites on Earth are rocks blasted off the moon and Mars, most are thought to come from the asteroid belt. However, for years, scientists had a hard time figuring out which asteroids the meteorites came from.

The problem is that scientists can study meteorites on Earth directly to see what they are made of, but finding out what the composition of asteroids are is complicated by the fact that they are both relatively small and distant.

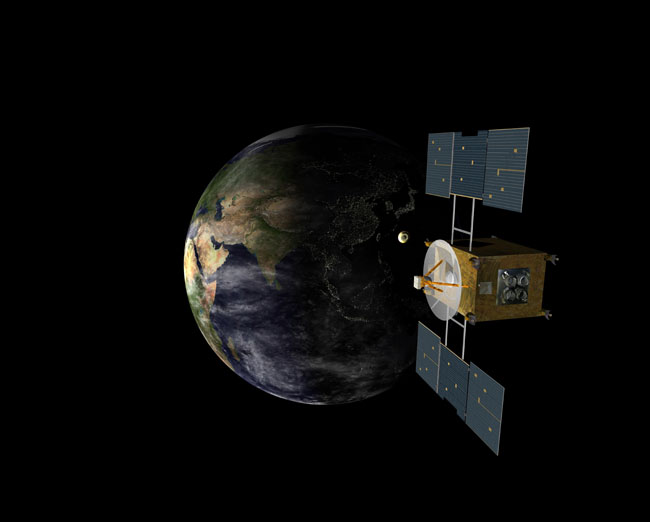

For a long time, as far as telescopes could tell, the chemistry of asteroids and meteorites often did not match. Recently spacecraft aimed directly at the asteroids, such as NASA's Galileo and NEAR Shoemaker probes, helped shed light on this mystery, suggesting that stony meteorites known as chondrites come from similarly rocky, S-class asteroids. Any apparent differences in composition could be due to weathering the asteroids undergo in space from radiation and impacts with other rocks.

"The planned return of a sample from an asteroid with Hayabusa could take that next major step in confirming what we think we know about the link between S-class asteroids and ordinary chondrites," said planetary scientist Dan Durda of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo.

Dustless asteroids?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Hayabusa found the small near-Earth rocky asteroid it visited, Itokawa, lacked the deep, powdery layers of regolith, or dirt, seen on larger rocky asteroids such as Eros.

"Hayabusa helped answer the question of what the surface a small asteroid looked like, but then it raised a whole new question ? what about the dynamics of the surfaces of small asteroids might clear them of regolith?" said planetary scientist Jay Melosh of Indiana's Purdue University.

Instead of getting stripped off Itokawa, any fine regolith it had might have actually drained inward to its center in a version of the so-called "Brazil nut effect," where small nuts tend to fall through crevices to sit on the bottom of a can while large nuts end up sitting on top. Gravitational pulls the asteroid experienced from close passes by Earth might have further rearranged these dust grains, Melosh noted. "Near-Earth asteroids might form very different surfaces from main belt ones," he said.

What is the brightest asteroid?

The brightest asteroid is Vesta, with a surface mysteriously some three times as bright as Earth's moon. Its unusual brightness suggests it might possess a strong magnetic field, which could help shield it from particles driven by the solar wind that would ordinarily dirty the asteroid.

The Dawn spacecraft is currently venturing to Vesta and the largest body in the asteroid belt, Ceres, but "Dawn doesn't have a magnetometer to figure that out," Durda noted. "It'd be nice to have one on a future mission."

Are we in danger?

As a near-Earth asteroid, Itokawa represents the first asteroid a space mission has ever visited that is potentially hazardous to humanity. So far, 812 near-Earth asteroids more than a half-mile (1 km) wide have been found.

Scientists have ruled out the chances of an Earth impact for all of these large objects, but lesser objects also pose a risk, and researchers estimate dozens of large near-Earth objects remain to be found.

Researchers are gaining an ever better knowledge of how asteroids behave. For instance, NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, could help scientists better understand the so-called Yarkovsky effect, where the steady release of solar heat from a rotating asteroid or other body can push it through space. "Measuring the force of the Yarkovsky effect would certainly be useful in modeling," Wright said.

- Images ? Asteroids Up Close

- Gallery ? Stardust Probe Returns Comet Pieces to Earth

- Video ? Killer Asteroids and Comets

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us